If we want open software to win, we need to get off our armchairs and compete.

The reason Facebook dominates the Internet is that while we were busy having endless discussions about open protocols, about software licenses, about feed formats and about ownership, they were busy fucking making money.

David Weinberger writes in the Atlantic:

In the past I would have said that so long as this architecture endures, so will the transfer of values from that architecture to the systems that run on top of it. But while the Internet’s architecture is still in place, the values transfer may actually be stifled by the many layers that have been built on top of it.

In short, David worries that the Internet has been paved, going so far as to link to Joni Mitchell's Big Yellow Taxi as he does it. If the decentralized, open Internet is paradise, he implies, then Facebook is the parking lot.

While he goes on to argue, rightly, that the Internet isn't completely paved and that open culture is alive and well, the assumption that an open network will necessarily translate to open values is obviously flawed. I buy into those values completely, but technological determinism is a fallacy.

I've been using the commercial Internet (and building websites) since 1994 - which is a lifetime in comparison to some Internet users, but makes me a spring chicken in comparison to others. The danger for people like us is that we tend to think of the early web in glowing terms: every website felt like it was built by an intern and hosted in a closet somewhere (and may well have been), so the experience was gloriously egalitarian. Anyone could make a home on the web, whether you were a megacorporation or sole enthusiast, and it had an equal chance of gaining an audience. Many of us would like this web back.

Before Reddit, there were Usenet newsgroups. (I'll take a moment to let the Usenet faithful calm down again.) Every September, a new group of students would arrive at their respective universities and get online, without any understanding of the cultural mores that had come before. They would begin chatting on Usenet newsgroups, and long-standing users would groan inwardly as they quietly taught the new batch all about - remember this word? - netiquette.

In September, 1993, AOL began offering Usenet access to its commercial subscribers. This moment became known as "the eternal September", because the annual influx of new Internet users became a constant trickle, and then a deluge. There was no going back, and the Internet culture that had existed before began to give way to a new culture, defined by the commercial users who were finding their way online.

"Eternal September" is a loaded, elitist term, used by people who wanted to keep the Internet for themselves. As early web users, rich with technostalgia and a warm regard for the way things were, we run the risk of carrying the torch of that elitism.

The central deal of the technology industry is this: keep making new shit. Innovate or die. You can be incredibly successful, making a cultural impact and/or personal wealth beyond your wildest dreams, but the moment you rest on your laurels, someone is going to eat your lunch. In fact, this is liable to happen even if you don't rest on your laurels. It's a geek-eat-geek world out there.

For many people, Facebook is the Internet. The average smartphone user checks it 14 times a day, which of course means that a lot of smartphone users check it far more than that. In the first quarter of this year, Facebook had 1.44 billion monthly active users. That means that almost 20% of the people on Earth don't just have a Facebook account: they check it regularly. In comparison, WordPress, which is probably the platform most used to run an independent personal website, powers around 75 million sites in total - but Apple's App store has powered over 100 billion app downloads.

Are all those people wrong? Does the influx of people using Facebook as the center of their Internet experience represent a gargantuan eternal September? Or have apps just snuck up and eaten the web's lunch?

Back in 2011, I sat on a SXSW panel (yes, I'm that guy) about decentralized web identity with Blaine Cook and Christian Sandvig. While Blaine talked about open protocols including webfinger, and I talked about the ideas that would eventually underly Known, Christian was noticeably contrarian. When presented with the central concepts around decentralized social networking, his stance was to ask, "why do we need this?" And: "why will this work?"

In the Atlantic, David Weinberger references Christian's paper "The Internet as the Anti-Television" (PDF), where he argues that the rise of CDNs and other technologies built to solve commercial distribution problems have meant that the egalitarian playing field that we all remember on the web is gone forever. While services like CloudFlare allow more people than ever before to make use of a CDN, it requires some investment - as do domain names, secure certificates, and even hosting itself. (The visual and topical diversity of GeoCities and even MySpace, though roundly mocked, was very healthy in my opinion, but is gone for good.)

For most people, Facebook is faster, easier to use, and, crucially, free.

Rather than solving these essential user problems, the open web community disappeared up its own activity streams. Mailing list after mailing list filled with technical arguments, without any products or actual technical innovation to back them up. Worse, in many organizations, participating in these arguments was seen as productive work, rather than meaningless circling around the void. Very little software was shipped, and as a result, very little actual innovation took place.

Organizations who encourage endless discussion about web technologies are, in a very real way, promoting the death of the open web. The same is true for organizations that choose to snark about companies like Facebook and Google rather than understanding that users are actually empowered by their products. We need to meet people where they're at - something the open web community has been failing at abysmally. We are blindsided by technostalgia and have lost sight of innovation, and in doing so, we erase the agency of our own users.

"They can't possibly want this," we say, dismissively, remembering our early web and the way things used to be. Guess what: yes they fucking do.

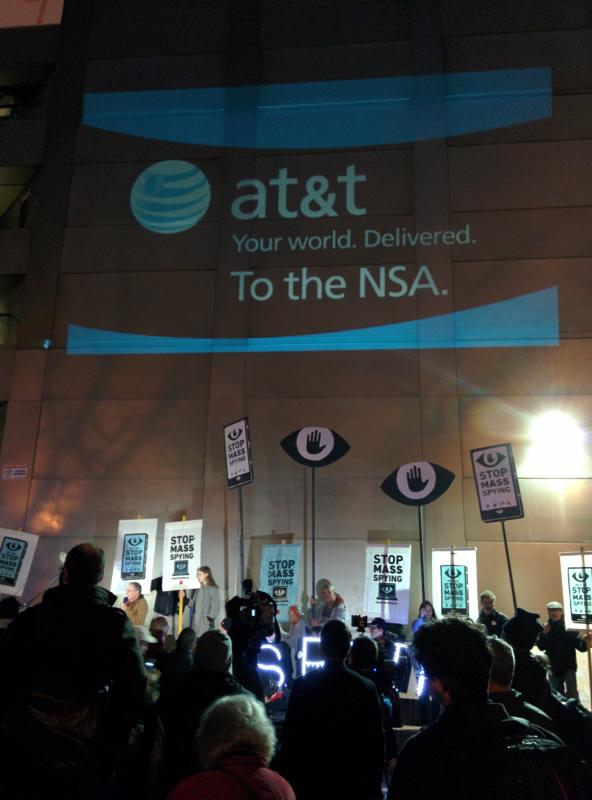

This stopped being a game some time ago. Ubiquitous surveillance, diversity in publishing and freedom of the press are hardly niche issues: they're vital to global democracy. A world in which most of our news is delivered to us through a single provider (like Facebook), and where our every movement and intention can be tracked by an organization (like Google) is not where any of us should want to be. That's not inherently Facebook or Google's fault: as American corporations, they will continue to follow commercial opportunities. It's not a problem we can legislate or just code away. The issue is that there isn't enough of a commercial counterbalancing force, and it really matters.

Part of the problem is that respectful software - software that protects a user's privacy and gives them full control over their data - has become political. In particular, "open source" has become synonymous with "free of charge", and even tied up with anti-capitalism causes. This is a mistake: open source and libre software were never intended to be independent from cost. The result of tying up software that respects your privacy with the idea that software should come without cost is that it's much harder to make money from it.

If it's easier to make money by violating a user's autonomy than protecting it, guess which way the market will go?

A criticism I personally receive on a regular basis is that we're trying to make money with Known (which is an open source product using the Apache license). A common question is, "shouldn't an open source project be free from profit?"

My answer is, emphatically, no. The idea behind open source and libre software is that you can audit the code, to ensure that it's not doing something untoward behind your back, and that you can modify its function. Most crucially, if we as a company go bust, your data isn't held hostage. These are important, empowering values, and the idea that you shouldn't make money from products that support them is crazy.

More importantly, by divorcing open software from commercial forces, you actually remove some of the pressure to innovate. In a commercial software environment, discussing an open standard for three years without releasing any code would not be tolerated - or if it was, it would be because that standard was not significant to the company's bottom line, or because the company was so mismanaged that it was about to disappear without trace. (Special mention goes to the indie web community here, for specifically banning mailing lists and emphasizing shipping software.)

The web is no longer a movement: it's a market. There is no vanguard of super-users who are more qualified to say which products and technologies people should use, just as there should be no vanguard of people more qualified than others to make political decisions. Consumers will speak with their wallets, just as citizens speak with their votes.

If we want products that protect people's privacy and give people control over their data and identities - and we absolutely should - then we have to make them, ship them, and do it quickly so we can iterate, refine and make something that people really love and want to pay for. This isn't politics, it's innovation. The business models that promote surveillance and take control can be subverted: if we decide to compete, we can sneak up and eat their lunch.

Let's get to work.