Tantek Çelik has posted a lovely encapsulation of the indieweb:

The #IndieWeb is for everyone, everyone who wants to be part of the world-wide-web of interconnected people. The social internet of people, a network of networks of people, connected peer-to-peer in human-scale groups, communities of locality and affinity.

This complements the more technical description on the indieweb homepage:

The IndieWeb is a community of independent and personal websites connected by open standards, based on the principles of: owning your domain and using it as your primary online identity, publishing on your own site first (optionally elsewhere), and owning your content.

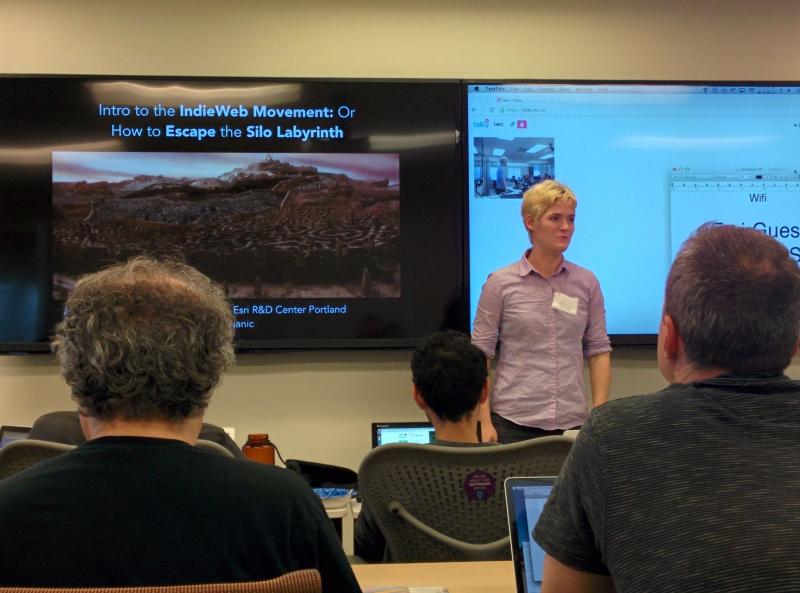

I first came across the indieweb movement when I’d just moved to California. Tantek, Kevin Marks, Aaron Parecki, Amber Case, and a band of independent developers and designers were actively working to helping people own their own websites again, at a time when a lot of people were questioning why you wouldn’t just post on Twitter and Facebook. They gathered at IndieWebCamps in Portland, and at Homebrew Website Camp in San Francisco.

One could look at the movement as kind of a throwback to the very early web, which was a tapestry of wildly different sites and ideas, at a time when everybody’s online communications were templated through web services owned by a handful of billion dollar corporations. I’d prefer to think of it as a manifesto for diversity of communications, the freedom to share your knowledge and lived experiences on your own terms, and maintaining the independence of freedom of expression from business interests.

A decade and change later and the web landscape looks very different. It’s now clear to just about everyone that it’s harmful for all of our information to be filtered through a handful of services. From the Cambridge Analytica scandal through Facebook’s culpability in the genocide against the Rohingya people in Myanmar, it’s clear that allowing private businesses to own and control most of the ways we learn about the world around us is dangerous. And the examples keep piling up, story after story after story.

While these events have highlighted the dangers, the indieweb community has been highlighting the possibilities. The movement itself has grown from strength to strength: IndieWebCamps and Homebrew Website Clubs are now held all over the world. I’ve never made it to one of the European events – to my shame, it’s been years since I’ve even been able to make it to a US event – but the community is thriving and the outcomes have been productive.

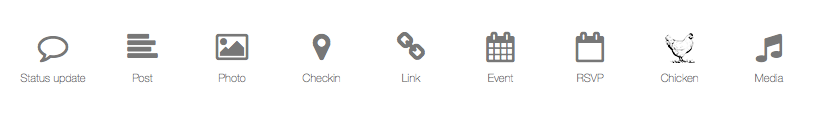

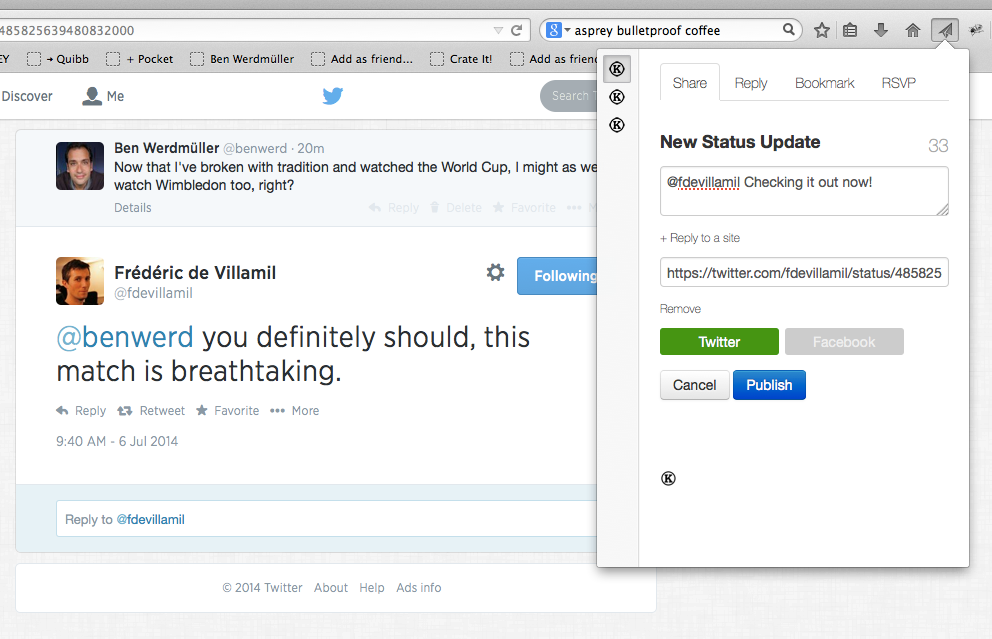

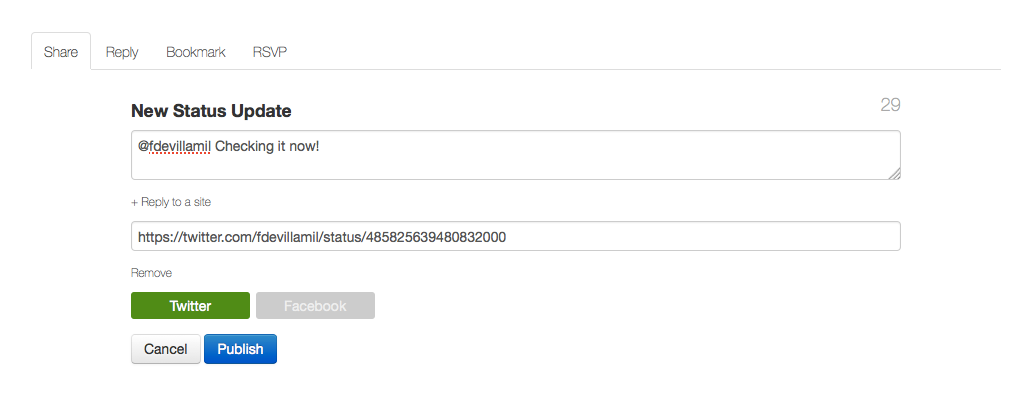

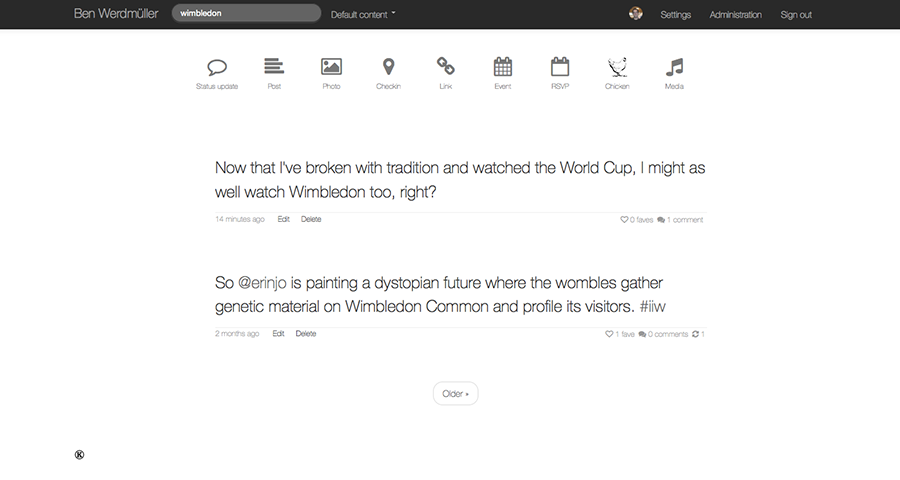

Even before the advent of the fediverse, the indieweb community had built tools to allow websites to connect to each other as a kind of independent, decentralized social web. Webmention, in conjunction with lightweight microformats that extended HTML to provide semantic hints about the purpose of content on a website, allowed anyone to reply to any website article using a post on their own site – not just that, but they could RSVP to events, send a “like”, reshare it, or use verbs that don’t have analogies in the traditional social networks. The community also created micropub, a simple API that makes it easy to build tools to help people publish to their websites, and a handful of other technologies that are becoming more and more commonplace.

In the wake of the decline of Twitter, Google’s turn towards an AI-driven erosion of the web, and a splintering of social media, many publishers have realized that they need to build stronger, more direct relationships with their communities, and that they can’t trust social media companies to be the center of gravity of their brands and networks. For them, owning their own website has regained its importance, together with building unique experiences that help differentiate them, and allow them to publish stories on their own terms. These are truly indieweb principles, and serve as validation (if validation were needed) of the indieweb movement’s foundational assumptions.

But ultimately it’s not about business, or technology, or any one technique or facet of website-building. As Tantek says, it’s about building a social internet of people: a human network of gloriously diverse lived experiences, creative modes of expression, community affinities, and personalities. The internet has always been made of people, but it has not always been people-first. The indieweb reminds us that humanity is the most important thing, and that nobody should own our ability to connect, form relationships, express ourselves, be creative, learn from each other, and embrace our differences and similarities.

I’m deeply glad it exists.

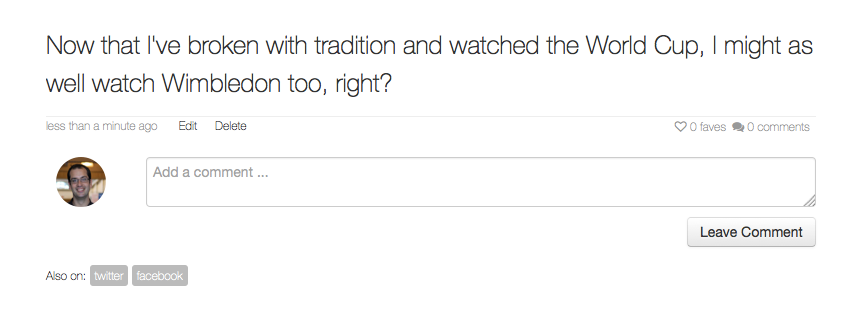

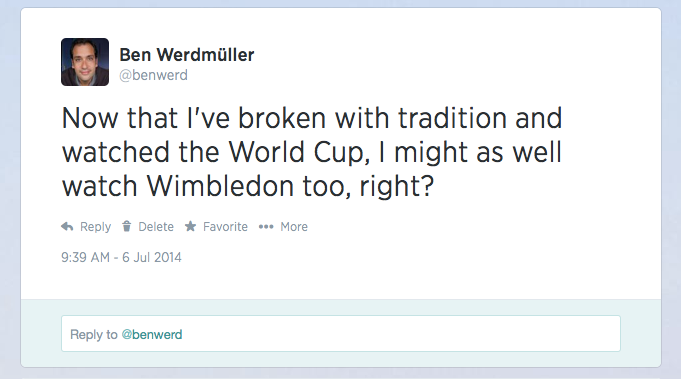

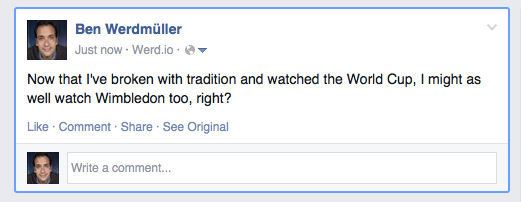

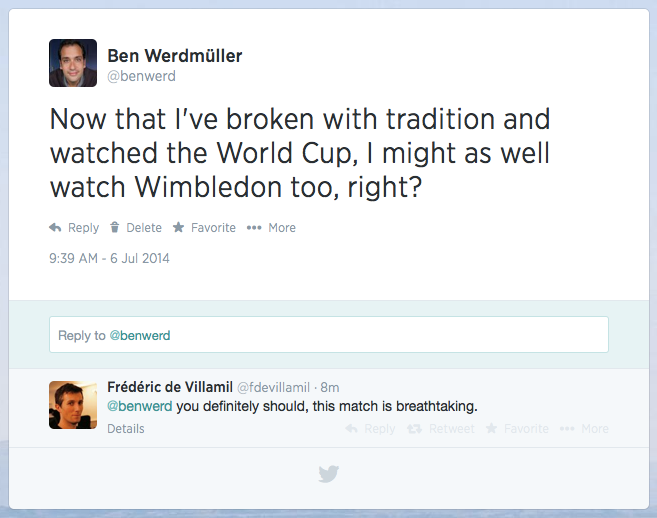

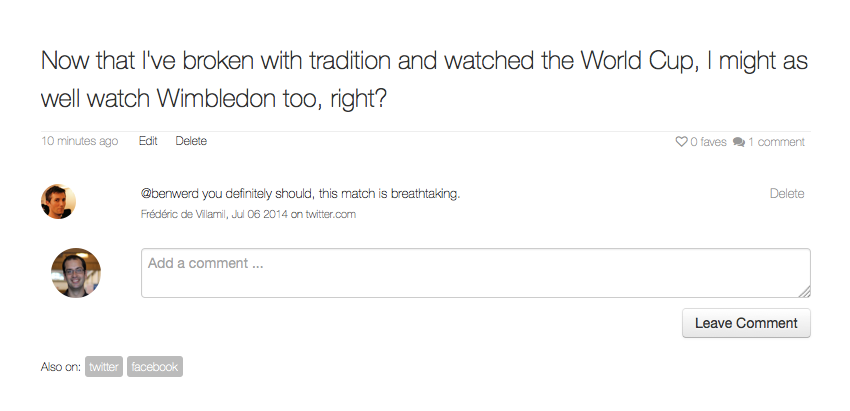

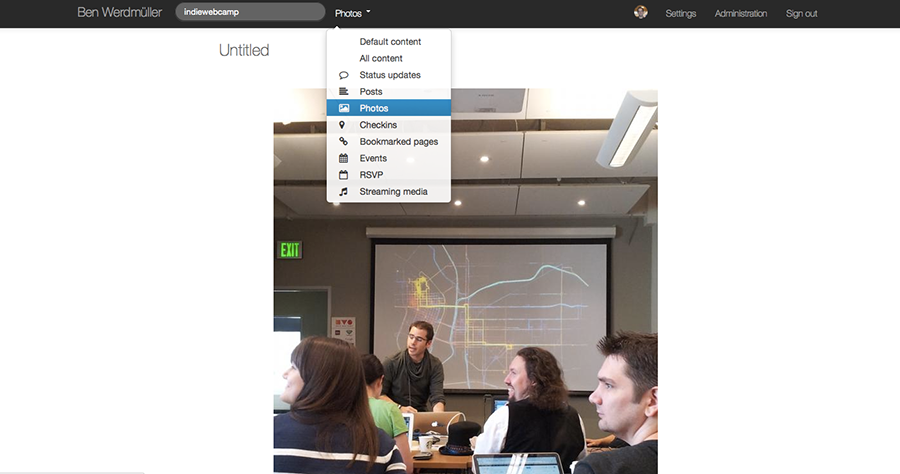

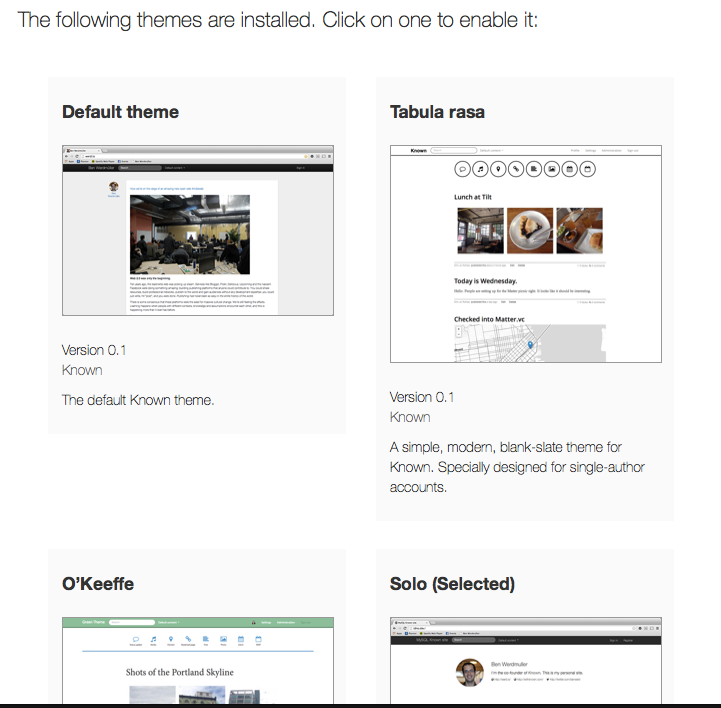

Known is a platform for a new kind of social web. You can think of each Known site as being a single social profile, either for an individual or a group. Each one can interact with each other in a decentralized way (using

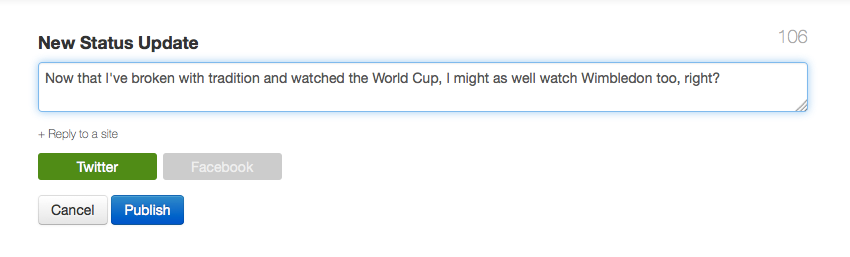

Known is a platform for a new kind of social web. You can think of each Known site as being a single social profile, either for an individual or a group. Each one can interact with each other in a decentralized way (using  On any device, ownership of your site and content, combined with an understanding of your community, gives you a new kind of clarity about your online self. You know exactly who can see each item you post. You know who's responding to you on which networks, and you understand which kinds of content your audiences are interested in. Known is both a safe space to reflect, and a singular site that represents you on the web. And more than anything else, it's respectful software that puts you at the center of your online world.

On any device, ownership of your site and content, combined with an understanding of your community, gives you a new kind of clarity about your online self. You know exactly who can see each item you post. You know who's responding to you on which networks, and you understand which kinds of content your audiences are interested in. Known is both a safe space to reflect, and a singular site that represents you on the web. And more than anything else, it's respectful software that puts you at the center of your online world.

Friday marked the end of my first full-time week at

Friday marked the end of my first full-time week at