Surfing the stress curve

It’s no secret that I’ve been pretty stressed out.

Someone I trust said that my writing lately has given the impression of “a man on the edge”. I think of it slightly differently - there’s a lot going on and I feel like I’m dealing with it in good humor - but I accept the idea and the intent behind it.

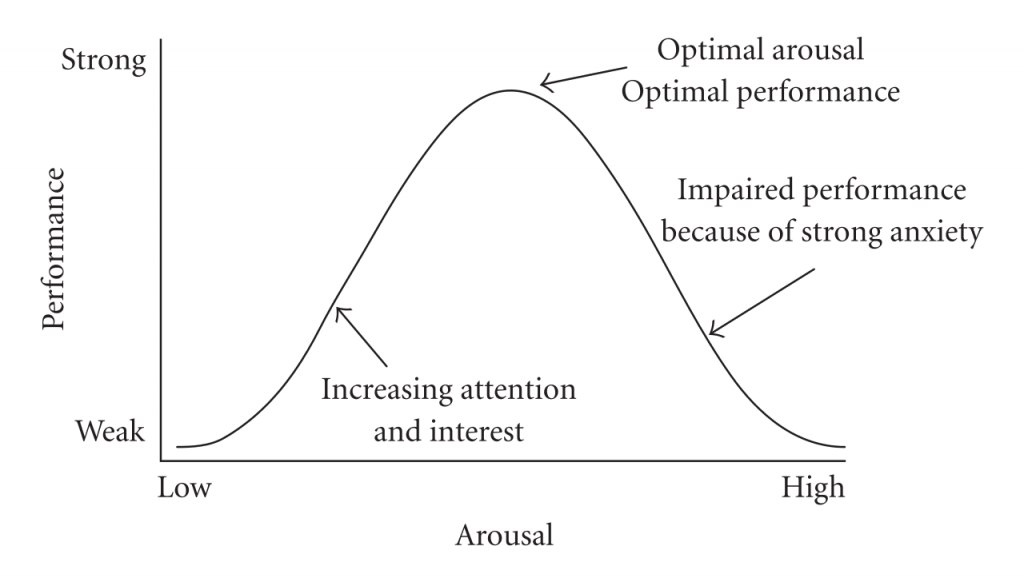

One of the most useful concepts I’ve been introduced to over the last couple of years is the Yerkes-Dodson curve. I’m not a psychologist, so please excuse my layman’s explanation: the idea is that we’re at peak performance when we have an optimal level of sensory arousal. Too little arousal and we’re maybe increasing our level of interest, but not in the zone yet; too much and we burn out quickly.

In contexts where there’s a lot going on, you’re already further along the curve. Because you’re nearer to burnout as a starting position, cognitive input that might ordinarily be okay has the potential to push you over the edge.

It’s a reductive explanation - again, I’m far from a psychologist - but I’ve found that it works for me. Applying this kind of structure to the process by which it all becomes too much has allowed me to think about what those cognitive inputs are, and to build in systems of control to keep myself on the straight and narrow.

I first put this to the test a couple of years ago. My mother’s condition had worsened, and I was feeling utterly overwhelmed, which was deeply affecting my performance at work.

At the same time, I’d become addicted to some game on my phone, and was traveling to and from New York a lot. I’d pick up my phone on the plane and play the game for an hour or two; depending on the day, I might play it a little in my AirBnb after work. There were a lot of notifications involved: lots of input.

In the scheme of things, the game was just a distraction. The big input was my mother’s terminally declining health, which was something that was always going to affect me psychologically, and wasn’t something I could or wanted to cut out of my life. (I can’t imagine what this would even have looked like.) Nonetheless, deleting the game dramatically improved my mental state. I was surprised, but it was undeniable: I was calmer, performed better at work, showed up more effectively for my family, and even had better sleep.

Abstracting this idea has resulted in a rudimentary system of control for my own stress. If I’m finding myself going over the edge - as happened this last week - I take stock of my inputs and reduce them. There are two more systemic solutions: find ways to become a more efficient processor of inputs (physical and mental exercise both help here), and create contexts for myself where there are fewer inputs overall.

Social media is one set of inputs. I’m going to try and take a break over the next month: removing all apps and logging myself out of the websites. It’s not that social media is bad, as such: it’s just one major set of cognitive inputs that can be removed. On the other hand, I find writing and blogging to be closer to a meditative process, so I’ll keep doing that. If I feel better at the end of the month, I’ll come back to social; otherwise I’ll leave it a little longer.

The same principle applies at work. The more chaotic and un-streamlined a process, the more cognitive inputs it produces, and the more stressed a team will be. Structure (or at least, the right amount of it) leads to predictability. Similarly, the more a process depends on ongoing meetings, the more inputs you receive during the workday. Zoom fatigue is both real and related to this principle: each meeting an input, each unscheduled meeting even more so. The more calm, reflective time I have, the more optimal my performance will be - which is, of course, different for everyone, because we all start at different places on the stress curve.

We’re still in the middle of a modern plague. Everyone’s stress level is higher than it would have been: not just because of the underlying context, but because many of us have lost family and friends. Creating conditions for our optimal well-being and performance means limiting stress, controlling our inputs, and more than anything, an intentionality that we might not have felt the need for before.