Telomeres, my son, and me

I bawled my way through Nowhere Special, a 2020 movie about a terminally ill man who needs to find a new family for his four year old son. I’ll be thinking about it for years.

It’s the story of a window cleaner with a terminal illness who needs to find a new family for his four year old son. The whole thing is perfectly understated, beautiful in its portrayal of a particular kind of love, but completely devastating.

The film sits at the intersection of a lot of things for me. Daniel Lamont, who played the four year old Michael, was reminiscent of my own three year old; so many of the furtive looks, reactions, and responses were echoes of my own son, so indicative of our own relationship.

A little over four years ago I had to say goodbye to my mother. She had a genetic disorder called a TERT mutation that interferes with the production of the enzyme telomerase, which normally protects your telomeres.

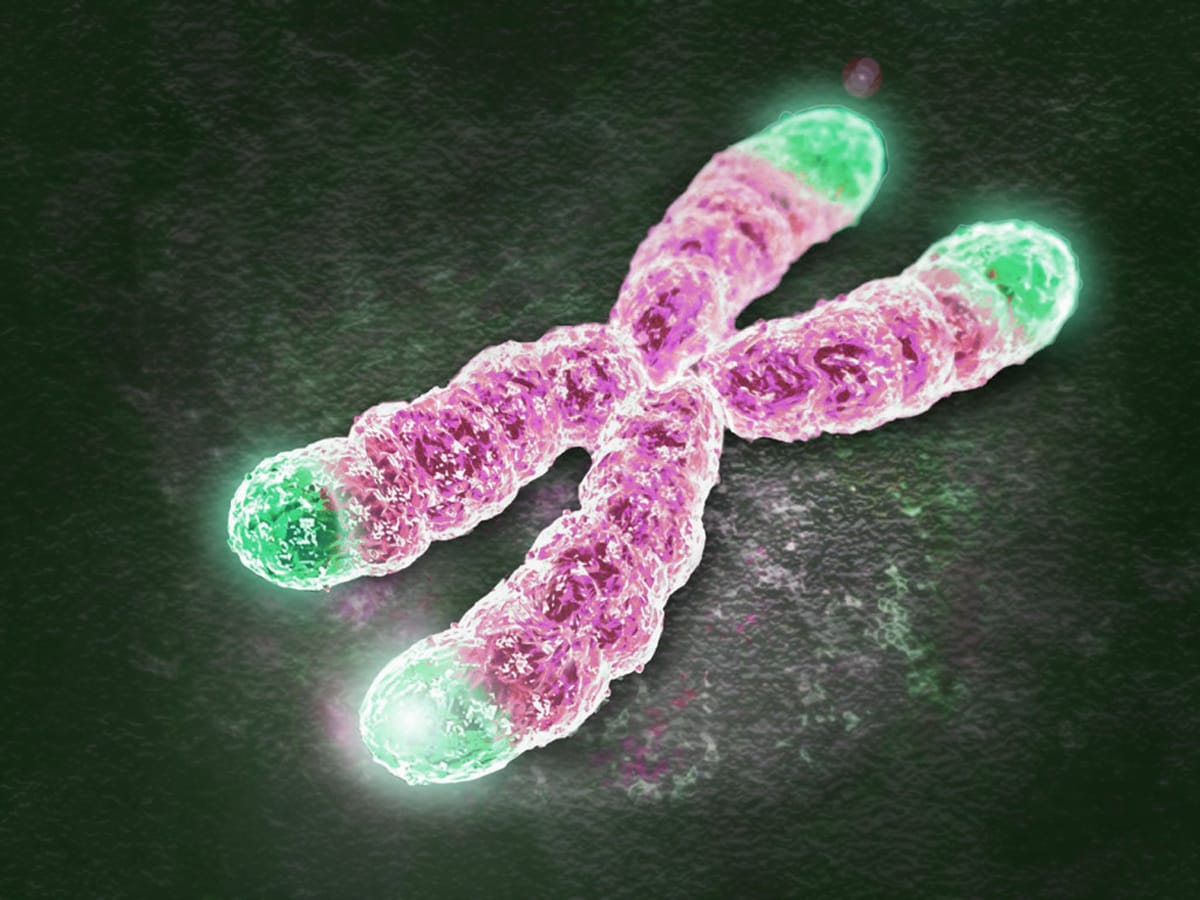

You can think of telomeres as the end-caps of your chromosomes; they normally shorten as your cells divide, and therefore become shorter and shorter as you age. Eventually, when they become too short, the cell enters senescence, and the cell dies. If you don’t have adequate telomerase, your telomeres shorten artificially quickly, and your cells enter senescence early. In my mother’s case, that led to pulmonary fibrosis: a condition where your lungs progressively scar up, making it harder and harder to breathe.

Because TERT is genetic, it runs in the family. So far, five members of my family have died from it. For around a decade, I was sure that I would too. We lost members of my mother's generation in their sixties; my cousins were younger. Going by that pattern, I wouldn't have much time left. In 2018, the science had progressed enough for me to be able to take a genetic test, which found that I don’t have the trait. It was bittersweet to say the least, but I’m glad that my mother was able to know that she hadn’t passed it on.

The science has advanced again. In particular, our understanding of epigenetics means that it’s perfectly possible to have inherited artificially short telomeres, and even dysfunctional telomerase production, without having the genetic trait. I have reason to believe that this might be the case for me, so a few weeks ago, while I was in San Francisco for a work trip, I submitted to a telomere length test at UCSF. I’m still waiting for the results.

We don’t know enough, and the science around telomeres continues to evolve. If I have short telomeres, it could mean that I will die young. Telomeres can also be affected by other environmental factors, so I would certainly make lifestyle changes to help protect them (and, in fact, I already am). But as I write this, there’s a real chance I will leave my best buddy behind far earlier than I would like.

Many people have to deal with these kinds of confronting situations (and far worse, of course). But it is confronting. And it brings up the kinds of questions that are worth asking regardless, in any situation: what does it look like to be the best parent possible in the time I have? How can I make sure that I set him up as well as I can for life? How can I optimize for being present and making wonderful memories together? How can I be the best possible person as we navigate childhood and parenthood together?

When my mother died, I made a resolution to be more representative of her values. I haven’t always lived up to this, and I was frankly a total mess in the year afterwards in particular, but it was the core reason that I shifted into working inside non-profit newsrooms. I’m really grateful for the upbringing I had: a non-traditional journey that involved multiple countries and parents who were oriented towards togetherness, internationalism, and equity from first principles rather than personal gain or living according to traditional templates. How can I give my son something similar? And working backwards from that, what should our family life look like?

These are heavy questions.

Nowhere Special has 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. If you haven’t yet, I’d go check it out.