There's no such thing as neutral technology

Why organizations must evaluate values, not just features

At the News Product Alliance Summit in Chicago this month, I took part in a panel discussion about building a community-focused ethic of news technology, and facilitated a related workshop on picking tools that match your values. It’s about newsrooms, but the lessons apply to any organization.

This post proposes a way to think about technology assessments not just in terms of cost or capability, but in terms of values. Values alignment isn’t a nice-to-have: misaligned values create risk that could cause major problems for an organization later on.

We often treat technology as being neutral, logical, and deterministic. But there is no such thing as neutral technology.

In reality, software is a creative work, just as journalism is a creative work. It’s made by people. Every design and engineering decision is a reflection of their goals, values, strategy, skills, resources, and foibles.

Technology always encodes power relationships. What a software development team considers to be unimportant is just as crucial as what they consider to be important.

The impact of a company’s values tends to grow as it becomes bigger and more powerful.

If a team values revenue from targeted advertising but doesn’t value user privacy, it could find itself building a surveillance network that could later be used by a government to deport students who happened to click like on an Instagram post, as has been happening this year.

If a team does not contain people from a diversity of backgrounds, it might find itself building predictive algorithms that penalize people of color, like the ones researchers like Dr Joy Buolamwini have uncovered.

Or if a team values hockey-stick growth but doesn’t value local relationships, it might find itself enabling a genocide, as Facebook did in Myanmar.

When we bring a technology into our newsrooms — or into any organization — and particularly when we embed it into our workflows, we import the assumptions and values of the people who made it. The things they think are important to encode — and the things they don’t think are important to protect.

Let’s make this more concrete.

A newsroom uses a proprietary CMS. Its features look beautiful and it claims to have excellent AI integration. But a few years later, its parent company decides it’s not working out, and pivots away from the product. Export options are limited; URLs break. Years of local reporting disappear from the web.

The tool worked, until it didn’t, and now the newsroom is held hostage.

It’s worth considering: what did the people who made this tool assume about permanence? About the importance of the newsroom’s control over its own work? And how does that differ to how the newsroom thinks about control over its work?

Here’s a second example: a newsroom adopts a tool that speeds up its hiring process using AI. The technology sifts through resumes and pre-screens applicants.

But as a University of Washington research team found out last year, that AI-based screening replicates and amplifies societal biases:

LLMs favored white-associated names 85% of the time, female-associated names only 11% of the time, and never favored Black male-associated names over white male-associated names.

What testing did the people who built these tools undertake? When research discovers this level of bias, how much do we think the vendors cared about building equitable software?

Do we think a newsroom that buys such a tool feels the same way or wants to further these systemic effects? Probably not, but by using the tool, they do it anyway – importing the values of the vendor.

These aren’t edge cases; this is what happens when we don't evaluate values alignment upfront.

In journalism, we have a duty of care to our communities.

We must be good stewards of the safety of sources who reach out to us. If a federal employee sends us information we use for a story, we must be able to keep them anonymous.

We must be good stewards of the people who read our information. If a person reads about where to get contraceptive healthcare from our website, we must not capture data about them that could lead to a prosecution.

We must be good stewards of our journalists, our donors, and the people who put themselves on the line for us so the truth can be told. If someone donates to us, that information should not be usable against them.

Our newsrooms are a reflection of our values. Those values are important. They are core to the journalism we produce, and therefore to our value as organizations to our communities. We need to protect them.

But much of the tech used in journalism — analytics, hosting, ad tech, content management, and so on — isn’t made by journalists or newsrooms. Sometimes those values are aligned with ours, and sometimes they aren’t.

As we’ve seen, a team’s values have a greater impact on their actions over time. So if we leave misaligned values unexamined, we inherently create more risk over time.

When we do a technology assessment – if we do one at all – we’re not often asked to consider the values fit of a technology and a vendor. But if we fail to examine those things, they can come back to bite us.

For example, if we evaluate ChatGPT, we must decide if we trust OpenAI, and whether we’re comfortable with how it was built and trained. They’ve poured a lot of money into making sure we’re hyped about it — but we have to ask ourselves who made it? Who benefits? And whose values does it encode?

When we evaluate technology to bring into the newsroom, we need to consider the following:

- How well its form and capabilities meet our needs

- How well its cost meets our available resources

- How well its underlying assumptions meet our values

- Whether its benefits outweigh the risks

- Who benefits from its power dynamics

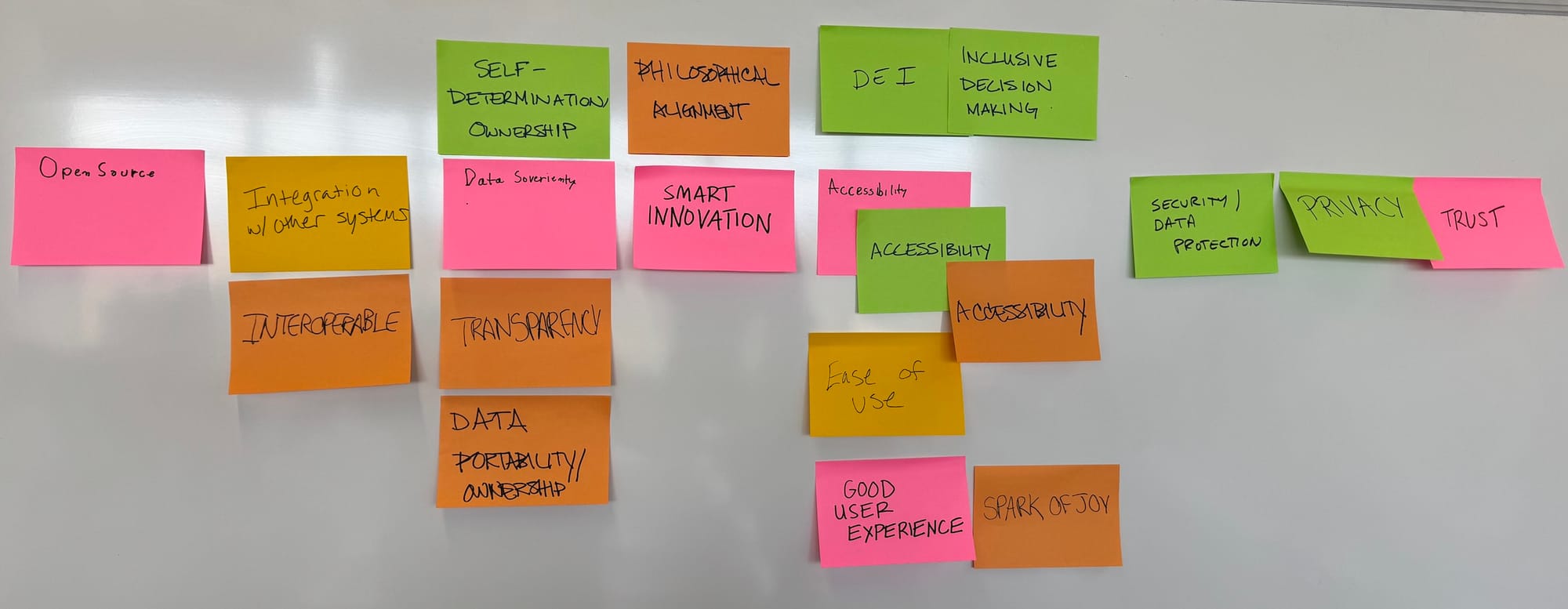

As part of a workshop at the News Product Alliance Summit in Chicago this October, I asked a room full of newsroom technology specialists to consider what values they considered to be most crucial when they made technology choices. While some participants emphasized the equity and representation of technology teams, most of them related to their ability to leave a platform if it ceased to be aligned:

- Data portability

- Open source

- Self-determination

- Interoperability

- Security / Data protection

Together, we built a rubric for assessing technology alignment that included smart questions like:

- Is the data ours?

- Could our data be exposed by a subpoena?

- If we delete data, is it removed from servers?

- Is it easy to export data in an easily consumable format?

This revealed something interesting: many technologists in newsrooms have already internalized that perfect alignment is impossible, so they're building escape hatches instead of trying to find perfect partners. These questions aren’t so much about ensuring values alignment as ensuring that a technology vendor’s values aren’t going to hold a newsroom hostage. By ensuring there’s a credible exit path from any platform, those value misalignments become less risky.

So what can we do?

Most newsrooms can’t — and shouldn’t — build much of their own software. But we can ensure that we can own our own data and use software on our own terms.

We can use third-party key encryption so that they physically can’t access our data without our permission. This is available as an option for many of the tools you already use, like Google Workspace, Slack, and AirTable.

Perhaps most powerfully, we can collaborate and build software together, to better fit our collective values. In the EU, governments are already building very highly functional collaboration suites to avoid trusting their data with US companies. Networks like Mastodon and Bluesky have been created as a values-based alternative to the surveillance-based status quo, and politicians are openly discussing the risks of depending on US software companies.

These dynamics are not limited to Europe. News often treats technology as something that happens to it, like an asteroid — but software is a creative work, just as journalism is. We have the expertise, the values, and the imperative. We can build the platforms that carry us. The future of independent journalism depends not just on what we publish, but on the tools we trust to carry it.