47 lessons

Things I've learned.

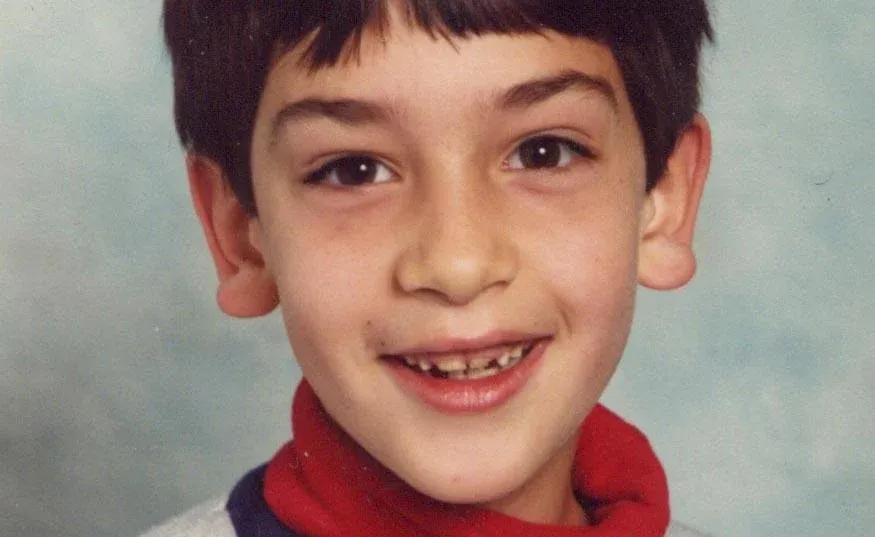

Every year, for my birthday, I collect my thoughts. This year I want to share some things I’ve learned: one lesson for each year I've been around. You might agree or disagree with them; maybe a bit of both. But they’re ideas I’ve picked up that, at the very least, are insights into how I think. Maybe they’ll be useful to you, too.

Previous birthday posts: 46 books, 45 wishes, 44 thoughts about the future, 43 things, 42 / 42 admissions, 41 things.

If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing slowly.

Every project, every major task, is worth taking your time over, both to plan and to do.

Most food cooks better if you do it with care, treating the ingredients, your tools, and the people who will eat what you’re making with respect. Most projects come together better that way too.

When I’ve rushed something together, I’ve almost always come to regret it.

You’ve got to make fucking up part of the process …

Aiming for perfection is a trap.

Even if you take things slowly, you’ll get stuff wrong. It’s part of doing anything meaningful. So rather than planning your project within an inch of its life, the best thing to do is start small, build in tests so you can figure out if you’re on the right track, learn from them, build incrementally, and keep going. The earlier you can get outside feedback, or some kind of signal from the outside world about whether you’re doing the right thing, the better.

I have this slightly reductive metaphor I use for both writing code and English, and I think it probably works for any project of substance:

Think of your project as a corridor. You have a bouncy ball and you need to get it to the end.

You could spend a long time trying to get a steady shot that hits the wall at the end of the corridor dead on. But you could also bounce the ball off the walls all the way down. It’s maybe less elegant, it’s maybe messier, but you still hit the wall at the end. And you probably get there a lot faster, with a lot less stress.

Another way to put it is this: if you accept that you’ll be wrong, you’ll approach your problem differently to how you would if you assumed you were right. You’ll talk to people earlier, you’ll get outside feedback, you’ll run tests. Even if you were right, those aren’t bad things to do. Conversely, if you assume you’re right, you probably won’t do anything to de-risk your idea, and you could still be wrong. And then you’ll have burned a bunch of time on something that doesn’t hit the mark, which might not have happened if you’d approached it with humility instead of hubris.

… Because fucking up is part of life.

Life is a project. You can assume you’ll do everything right or that you’re really smart, but that probably won’t get you very far. We all need feedback. We all need to learn and then course correct and then do it all over again. All we can do is iterate on ourselves.

Saying “I don’t know” is a superpower.

It’s weird to me how many people don’t: they’ll try and give you directions even if they don’t know the way to a place, or they’ll spin their wheels forever instead of suffering the indignity of going out and asking someone.

The cool thing about admitting you don’t know, and just asking someone if you need to find something out, is that it leads to a different kind of conversation. If someone asks me something and I don’t know the answer, particularly if there’s a vulnerability to not having that particular piece of knowledge, telling them lets them know that I’ll be real with them. But more than that, it just gets me to where I need to be faster. I’m not wasting time on face-saving bullshit. And there’s precious little time to waste.

What you pay attention to defines you.

You are what you tolerate. But you are also what you notice, what you spend time with, and what you choose to dismiss.

If you allow your attention to be shaped and manipulated by someone else, you are what they are trying to make you to be.

Pay attention to your attention.

When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.

I originally thought this famous advice was maybe unfair: didn’t it prioritize knee-jerk assessments? But it’s not about snap judgments; it’s not your first reaction to someone. It's about paying attention when someone actively reveals their values to you. If someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time. And I’ve come to understand that Maya Angelou is right.

Even the smallest red flags matter. The person who tells you the world would be better if men and women played to their gender’s strengths. The person who, on being inconvenienced by local rail drivers striking for better pay, exclaims that they can’t wait until they’re all replaced by robots. The person who is needlessly rude to a waiter or the person behind the desk at a coat check. These are the kinds of small exchanges that are indicators of a mindset that dictates how they show up in the world. It might seem kind to overlook them, but it’s wiser not to. There’s always something more.

You are what you tolerate.

What I mean by this is: if you allow something to continue, you help normalize it.

That goes big and small.

People often say this about management: if you tolerate mediocre work, your team becomes mediocre. And, sure, that’s important in a work environment.

But it’s also true in life. If you allow someone to regularly belittle you, you become belittled. If you allow someone to cause harm, you cause harm.

Every cry is a message.

When my son was a baby, I quickly learned that while babies can’t talk through words, they have a full spectrum of communication that, generally speaking, gets their point across. I’d assumed that babies were a little bit like that old app Yo, where the only notification you could send or receive was a one-note “yo”. That was so far from being true.

There’s no such thing as a cry that doesn’t have an underlying meaning, from the practical — I’m hungry, I’m uncomfortable — to the existential — I’m lonely, I need a hug.

We learn words, we pick up the cultural dressing of the society around us, but we don’t stop crying. Those underlying signals perhaps become more complicated as we age, but they’re still there, all around us as subtext behind what everyone says and does. There are the words, and there’s the message behind the words.

Communication is a muscle.

There’s a thing I learned from Corey Ford, which I think may have been inspired by some of the work Carole Robin did on interpersonal relationships at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business.

Open, 360-degree feedback is vital on any high-performing team (or functional community). If you let friction between people linger, it tends to grow, and can sink the culture of a team; it’s the kind of thing that kills startups and leads to people leaving companies. You need to be able to bring things up and talk about it in a non-accusatory way.

That doesn’t come naturally. So you have to practice.

He’s got a great process that I’ve used for over a decade called the one-on-one gift exchange. The details of it aren’t important here, although it’s worth checking out. He advises that you do it on a regular schedule, whether you have something specific to bring up or not. In doing so, you make giving and receiving feedback just a thing that you do regularly, and it makes it easier to give the hard feedback when it inevitably comes up.

All communication is like this. You’ve got to practice. And you’ve got to keep practicing, otherwise your communication skills atrophy. And it turns out that open, honest, bidirectional communication is essential to every kind of relationship, from business to families to romantic to friendships. Otherwise things build up and build up, and, if you leave them unaddressed, they snap.

Be careful about who you put on blast.

I came from a context that didn’t matter: some guy writing code in Edinburgh, way outside of the centers of tech or media power. I got used to being critical about products and teams. Some of those criticisms were meaningful; some were not.

The first time this bit me was when I worked at Medium. At some company happy hour (there were a lot of those during the era I was there), I talked about how silly a very famous product design was. “I built that,” someone said. Over time, my voice became more influential, as I took bigger roles. Despite this increased attention, I sometimes continued to run my mouth over stuff that didn’t matter, offending people for no reason.

Some things do matter. If you’re colluding with fascists, destroying the environment, or causing active, obvious harm, you deserve to be called out. On the other hand, a design decision or a voice that you don’t quite agree with deserves a little more care. Every single thing is made by real people with real lives and complicated contexts. There’s a difference between speaking truth to power and dunking on someone’s work. Choose your targets carefully.

Most dinner plates can hold over a pint of water.

Ask me how I know.

Plato’s cave is real.

If you’re not familiar with it, Plato’s allegory of the cave goes something like this:

Imagine prisoners who have spent their entire lives chained inside a cave facing a wall. Behind them is a fire; their captors cast shadows from various objects and puppets. Because those shadows are the only things they’ve ever known, they’re reality for the prisoners.

Imagine, then, that a prisoner is freed and compelled to leave. They see the fire; because they’ve never seen light so bright before, they’re temporarily blinded. Then they’re dragged outside and the sun is brighter still. Eventually, as their eyes adjust, the world outside is clearer and more detailed than the shadows ever were.

So the prisoner goes back into the cave to free the others. It’s dark in there, so they’re blinded again. The prisoners infer that whatever’s outside must have hurt the freed prisoner. So the freed prisoner must have been corrupted and whatever’s outside must be dangerous. They’ll defend themselves from being freed and dragged outside themselves, potentially to the death.

Here’s where I’ve come to differ with the common understanding of the parable:

Each of us is in our own cave. We don’t have a shared reality; we all get our own shadows.

The dangerous bit of the story isn’t being in the cave or being freed. It’s going back, or never having been a part of that particular cave to begin with and wandering in to provide perspective. There are so many people who believe their context is the right one, that the shadows they’re seeing aren’t just reality, but comfortable and right.

Take it from a Third Culture Kid who’s moved around a bit.

The more caves you’ve seen and the more times you’ve been forced into the light by the gift — or shock — of another perspective, the clearer you can see the limits of any one view of the world. But that's scary as hell for the people who won't adjust themselves to the light, who want their version of the cave to be everybody's.

If you've only ever lived in one town, one state, or one country, you're seeing narrow shadows of how the world works. We all know the people in the cozy town who see the arrival of outsiders as a threat to their “way of life”. Geography, culture, and the assumptions of the people we connect with shape what seems natural, what seems possible, what seems inevitable, and it can make a new perspective — which, too often, is a new person — feel like a threat.

Following someone else’s template is fine, but there’s more out there to see.

One of my favorite things is psychogeography: a way to explore built environments by taking arbitrary routes or following interpersonal, human-driven connections to places rather than taking a direct, logical route.

If you explore Venice, you’ll probably find the same tourist destinations as everybody else. That’s not nothing: they’re beautiful. But if you go and find, for example, the narrowest alleyway in Venice, you’ll leave the crowds, walk through neighborhoods where people actually live, and see more about the culture and nature of the city than if you’d stuck to the tour.

I would have earned a lot more money if I’d dedicated myself to engineering and just focused on software and product inside the tech industry. But it would have been a hell of a lot less interesting, and a hell of a lot less fulfilling. Meandering means going somewhere new.

The templates defend themselves.

I’ve found that the more someone adheres to a template for living, the more affronted they are by people who don’t adhere to one.

There’s a kind of xenophobia that’s at the root of conservatism. If you feel like being “normal” is a moral good, then it follows that someone who isn’t normal is immoral. They’re to be feared — and, potentially, converted.

Most overtly, we see that in peoples’ reactions to trans people, to marriage equality, or to immigrants coming from other cultures or with minority skin colors. But it also manifests in smaller intolerances: the microaggressions that many people have to deal with every day. It’s not just MAGA; it’s the libertarian, predominantly male norms of the software industry, or New York City’s implicit dress codes.

I’ve sometimes wondered if these templates provide some stability for people who struggle with empathy, who find it difficult to imagine another human being’s interior life. If you don’t know how other people work, established patterns can be reassuring. Conversely, people who don’t fit into them are unsettling.

For some reason, I give off a kind of conventional vibe, which means people feel safe sharing these fears with me. The British accent, “safe” haircut, and slightly self-deprecating demeanor don’t scream “part-Indonesian multinational third culture kid who cares about undermining centralized systems of power”. But that’s what I am.

So I’ve had those encounters. The guy who, over a drip coffee in San Mateo, told me that the problem with the world is that women don’t know their place anymore. The one who, at a pub in North Oxford, said that, you know, he doesn’t know what’s wrong with Europeans. The manager with the pristine haircut who complained that people who want inclusion “want so many other things”. And why doesn’t everyone speak English?

Spoiler alert: I am not a safe person to have those conversations with.

I tend to feel sorry for people who feel like they have to abide by a template, but that ebbs away as soon as they advocate for someone else’s subjugation. The templates defend themselves. But everyone deserves to live on their own terms.

There’s a fine line between knowing your limitations and living your life with a fixed mindset.

It’s really easy to say things like, “I don’t do heights” or “I’m a bad public speaker” in the same register as “I can’t reach high shelves” or “I’m allergic to peanuts”. But they’re different kinds of things.

The first are surmountable. You might not be a good public speaker now, but most great public speakers had practice. The question isn’t, “can you be a good public speaker”, but “do you want to be?” Because if you do, and you put your mind to it, you probably can.

I started out by wanting to write for a career. I’ve been a software engineer. I’ve founded two startups. I was a venture capitalist, somehow. I was also a film reviewer and a barista. I’ve sworn blind that I couldn’t draw and have also drawn well. Everyone changes. We’re all in flux. We can all grow.

You can never go back.

The only way out is through.

That’s true for industries and countries. We can wax nostalgic all we want about how it used to be, but (1) it probably never actually was exactly as we remember, (2) we can never go back there. Time doesn’t work that way. Even if we had a fully-kitted-out Delorean with a functional flux capacitor, our presence would change that reality. It cannot exist.

I sometimes find myself nurturing a kind of homesickness for different eras of my life. Some of them make me so sad that my chest aches. I miss people, I miss places, I miss the rhythms and values of my life back then. But I can’t go back. There’s no email I can send, no journey I can take, that will return me there. It’s more important to figure out what was so special about them, understand how important those values are to me, and make decisions about my future with them in mind.

And so much else. Rather than worrying about how the news industry used to be, we need to invent how it will be in the future. Instead of yearning for the glory days of the open web, we need to build something new. Instead of wistfully dreaming about a time before Donald Trump, we must prepare for the time after him. We all have to move forwards.

The original Thomas the Tank Engine theme will dislodge any earworm.

Of course, then you’ve got another problem.

Every system should be designed to ensure that the right things happen in the hands of the wrong person.

Most of the time, our work is in the hands of the right people. We make good decisions hiring, we bring new people we trust into our communities, and everything works well.

But sometimes that doesn’t happen. Maybe someone’s had a bad day, or they’re sick, or someone who doesn’t understand the context has to fill in for some other reason. Suddenly it becomes apparent that we don’t have systems of control: the most sensitive tasks don’t have safeguards that ensure the right thing happens. Our process has been based on norms and traditions rather than enforced checks.

These days, modern code is written using the Pull Request, a feature that was streamlined and therefore popularized by GitHub. Instead of an engineer just writing software into the codebase, they submit it as a change; another engineer checks it over and either requests changes or gives it the okay. Usually, an automated system also runs tests against it to make sure the code fits into the standards and guidelines of the codebase. The result is a system of control that has at least two levels of check: the human reviewer and the automated tests. Damaging mistakes can still happen, but far fewer than if you were writing code without oversight and uploading it directly to a production server.

Writing a rule, law, or process to contain a system of control isn’t a vote against the trustworthiness of whoever is responsible when it’s written. It’s a way of ensuring that whoever the next person is can’t abuse it.

There’s a lot that I could say about the second Trump administration. One way of looking at it is as a penetration test for American democracy: finding the parts of the American system of government that were held together with norms and traditions instead of well-defined systems of control.

That’s been the worst-case scenario. But the effect of every bad manager, every disgruntled employee, and every bad actor, big and small, can be mitigated by the same principle.

People trust people, not brands.

It stands to reason. A brand is a business entity’s marketing identity, which inherently is designed to manipulate you into having a reaction to it. Why would you trust that?

One of the remarkable things I’ve observed in journalism is that a lot of people in the industry assume that the general public should love them. Journalism provides a lot of societal value, so the fact that trust in it is at an all-time low means the public needs to be educated about it. The reason they don’t trust it is they don’t know enough about it!

I want to play the Family Feud buzzer sound here. Ehhh ehhh. The reason people don’t trust journalism is that it’s talking past them, not to them, and it’s certainly not listening to them. They see the logos and the wordmarks, rather than a real human being taking the time to be real with them. The lesson of young people turning to YouTube and TikTok is not that young people love vertical streaming video, it’s that they’re tired of corporate bullshit and want to see a real human face meeting them where they’re at.

It’s a scary prospect for a newsroom, or for any organization. A brand is an identity for the full collection of people. In contrast, a real human face is someone who might not always be employed at that company. If a community has built up a relationship with a person, they may leave when the person finds a new job. The brand owners want to invest in relationships they can keep for themselves.

But the public doesn’t care about that. They just want to have an actual conversation with a person. They’re looking for human authenticity and a personality that doesn’t try to authoritatively dictate the truth to them.

We all just want to connect with people, not be marketed at. It’s about relationships and humanity. Community doesn’t care about your ligatures. It wants to be seen.

Public gratitude is a reflection of who you think is important.

If only managers receive public gratitude from leadership for a team’s accomplishments, then the culture prioritizes hierarchy and devalues the contributions of the individual contributors who actually do the work.

If only certain roles receive gratitude from leadership, then the culture only really values those roles, and sees other positions as subordinate.

Over time, if people are doing hard but thankless work, they’re unlikely to stick around, and the work will suffer.

Everyone who shows up to work is making a contribution. What you’re doing couldn’t happen without them. They’re three-dimensional people who care about their place in the community and want to be respected. So treat them like they are — and thank them.

Everything you add is overhead.

If you’re on a team that writes code, every codebase you write from scratch is something new that you have to maintain. Write enough of those without increasing the size of the team and you’ll find that everybody is in maintenance mode all of the time. (Self-hosting someone else’s code has a similar maintenance overhead.)

If you’re in a company that buys services, every new service you buy is something new that you have to pay for. Subscribe to enough of these and you’ll find that you’re financially underwater and it’s harder to weather downturns or find profitability.

If you add complications to your life, the emotional and administrative overhead adds up in similar ways. You might think you can take it on, and you probably can, but as the complications and responsibilities grow, so does the overhead of living. And suddenly you might find that you’re tired and stressed all the time. The trick is, it sometimes happens without you really meaning it to. Life accumulates.

The trick is knowing which kinds of overheads you can manage, and when.

If you’re making something, you need to understand if you’re making art or building a business.

I’ve written a lot over the years about how if you’re making a product, you need to know who it’s for, and make sure it actually solves someone’s problem. “Scratching your own itch” is something that open source developers in particular do a lot of, but if you do that, you may spend a long time, and potentially a lot of money, working on something and find out at the end that it doesn’t quite solve a problem for anyone but you.

But that doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with scratching your own itch.

I think it’s the wrong way to go about starting a business (be it a startup, small business, or non-profit). In those situations, you need to know who your customers are, you do need to understand if what you’re making is useful, and you do need to understand if anyone will buy or support what you’re building in the context of the model you’ve created for it.

But not everything has to be a business. Not everything has to be sustainable.

There’s a word for a creative act that is self-led in this way, regardless of whether the medium is code or words or paint or anything else: art. It’s always okay to make art. We need more art, all the time. Art is one of the core things that makes us human; it’s one of the core substrates that holds society together.

But you’ve got to know whether you’re making art or building a business: whether your center of gravity, your great adjudicator, is your customers or your heart. By understanding this, you’ve set up your own expectations, and you know which tools to deploy. With art, you can follow your heart more ambitiously. With customers, you can obsessively serve them. In both cases, you can cut the ambiguity.

It’s not that one is more valuable than the other. They’re just different things.

Funding isn’t a values judgment, but it is a value judgment.

Back when I worked for Matter Ventures, we would have intense recruitment periods for our accelerator. For a few weeks, I’d work twelve hour days, sitting on a hard wooden stool at a homemade wooden table made out of a door, and listen to pitches from early-stage startups that hoped to obtain our funding. It ran the gamut from incredibly smart applications that I’d never seen before, through barely-there ventures fueled by magical thinking, to outright grifts.

A lot of first-time entrepreneurs were adamant that we should fund them because of their values. They were good people doing something ideologically wonderful in the world. They saw our investment like a magical grant.

But it wasn’t a grant. We were a mission-driven accelerator, investing in ventures with the potential to help create a more informed, empathetic, and inclusive society. But we were still a for-profit venture firm. We needed to invest in startups that had the potential to provide an exponential financial return. There were plenty of lovely people whose projects had lots of value — but we couldn’t fund them using our model.

When I was building Known, we couldn’t get investors to the point where they had conviction we would give them that return. They were very nice to us, and we had some good coffee conversations - but that’s where it ended. We couldn’t tell that story. The best founders pivot their startups until they’ve caught onto something that looks like it will grow quickly. That requires killing your darlings, as writers call it; letting go of the things you love that just aren’t working. That’s not what we chose to do.

Every venture fund is working for their limited partners (the people who put money into them). That’s most likely to be a financial return — ideally a startup will return a substantial multiple of the money that was invested into it — but it might also be a strategic return. (Consider why NVIDIA might invest in AI startups, or why the CIA might invest in social media - which, by the way, is a thing they do.) Every limited partner has a different agenda; every venture firm has its own investment hypothesis.

The same is true of non-profit grants, as it happens: donors put money into them, too, and they also have their own agendas.

None of it is a gift.

If you’re not raising money with the needs of the venture partners / non-profit funders and the agendas of the limited partners or donors in mind, you’re not taking it seriously. It’s not magic. It’s a financial transaction. You don’t get it because you deserve it; you get it because the funder thinks you’ll give them the return they need.

And of course, this is how power centralizes.

Turning it off and turning it on again works.

Nine times out of ten, it’ll fix your computer problem. Really. Try it before you ask someone else. I’m begging you.

Don’t stay up too late.

You need sleep. You really do. You only think you don’t because you don’t physically drop dead or stop talking when you’re underslept. But you’re basically another person. Go to bed.

You can’t show up for others if you don’t show up for yourself.

I’m not sure where it came from, but over time I developed a kind of shame just for being me: an underlying sense that there was something fundamentally wrong with me, but nobody would tell me what it was. It arrived one day when I was a teenager and never left. I imagined that there was a magic incantation that I didn’t know, but I could never be good enough. I’d never be worthy of the adulation I placed in other people; if I wanted to be liked, I needed to mask to be more like them. I desperately wanted someone to really see me and — despite that — know that I was okay.

The thing about feeling like you just need an ally, or someone who will tell you at last that you’re okay, is that it puts you in an incredibly vulnerable position. You don’t need someone who will tell you you’re okay; you don’t need a superficial ally. You need people who you can be in community with, who you can build relationships with over your life.

It creates vulnerability in another way, too. If you don’t like yourself, if you feel like you don’t matter, you can trick yourself into thinking that nothing you do matters, either. And there probably are people who care a great deal about you; consequently, what you do does matter. So you can make decisions that inadvertently hurt people you care about a great deal. You can fail to fight for relationships that have the potential to transform the entire fabric of your life. You can be passive about the stuff that really matters in life. You can find yourself in a place where you ignore your goals, values, and ideals.

So I’ve learned that you need to find ways to feel good about yourself; to respect yourself; to care for yourself. It’s not a selfish act. It allows you to show up in the way the people you care about need you to, which in turn allows you to build better relationships, better community with them. It allows you to take bets on yourself and build the life you really want to live. It allows you to be you, on a really fundamental level.

But if you don’t do that? The spiral is hard to escape from. The people you care about will tire of your disrespect. And those relationships may take years to repair.

Ask me how I know.

Mid-life aging is more about how your life changes than your body.

Yes, my metabolism is slower than it ever used to be. I’m definitely more tired. My back is a little more tense. I find it harder to shift into a creative mode.

But let’s look at how my life has changed. I have a much more demanding job and my time is less my own.

In my twenties I was the founder of a bootstrapped startup and could set my own parameters, including when I worked and when I didn’t. Nobody was checking my work except our customers: I had remarkable creative freedom. I didn’t have a kid, so I could walk seven or eight miles a day (and did). I hung out with friends more often, saw live music more often, went to the movies, and spent more of my life being active and having fun as a percentage.

I’m pretty sure that if I returned to that level of activity, my metabolism would increase. If I made more of a commitment to fun and had fewer parameters in my work, I would find it easier to shift into a creative flow state. If I was less stressed about money, I would sleep better at night. In fact, before my mother died, I was running 5K every day, and my body, my mind, and my soul, frankly, were all improving.

Let’s be clear: every body is different. Biology is real. But not every mid-life physical decline is inevitable. It’s that the demands on your time, your energy, your brain increase. There’s more overhead. And it takes a toll.

Grief lives in the body and flows like tides.

For a long time after she died, I could hear the gentle click of my mother breathing through her cannulas. It followed me home to her house in Santa Rosa, and across coasts to my new home in Elkins Park. Sometimes I could hear the wheels of her feeding tube stand rolling across the floor.

These sounds lived in me. I couldn’t let them go. Not with all they represented.

We washed her, my sister and I, right at the end. A final act of care. But not one of goodbye.

My cousin warned me that the grief could sneak up and grab you, unsuspecting, and it did: I found that I had to pull off the road or hide myself in a public bathroom and let it out. I don’t know what other people made of the sound of my sobbing, if they heard it. It didn’t matter.

It had been a long journey. I’ve written about it from time to time, partially to explain myself, and partially to exorcise it. It doesn’t represent my mother, and shouldn’t, except in that she fought with so much life-force, and maintained so much good humor and kindness until the very end. I want to remember her smiling at a joke or angry about the world, not her prone fragility in a hospital bed.

Grief is just this: the loss of her, the loss of the family with her in it, the loss of her life and our lives and how everything was before we knew she was going to die. Some days, moving forwards is easy. Some days, the sadness ambushes you, and it’s all you can do to keep breathing. Every day, I feel it in my limbs, in a new heaviness to every day. If you cut me open like a tree I’m sure you’ll see it in my rings.

Trauma comes in layers.

Grief is not the same thing as trauma.

The trauma is of seeing my mother in that bed, knowing she didn’t want to die in a hospital after that decade-long struggle, and not being able to do anything about it because the doctors she needed 20 liters of oxygen and she would have suffocated if we’d moved her.

It’s of learning what palliative care means, first-hand, and understanding that they would pump her with drugs and starve her until the end came.

It’s of seeing her at the bottom of the stairs and staying with her until the ambulance came.

It’s of yelling at her to wake up after the surgeon scraped off the crust around her lungs, her lips blue, her breathing shallow, and thinking this was really the end this time.

It’s of moving thousands of miles to be with her, sure she was about to die, sure that I would get the same sickness, and losing the person I thought I would spend my life with, not knowing if I had time left.

It’s of my cousins, and my aunt, and my Grandma. Everyone we have lost to this horrible disease.

It’s of, even now, not being able to dream about my mother, not hearing her voice except for the videos I took of her, except for that one time I heard her say, “oh my God, you guys,” clear as day in the dead of night.

It’s layered like rock, a thick crust of fight or flight burying layers of sadness and images that make me sit upright with my heart pounding.

I’ve only recently made peace with disrupting those layers and mining to its core. Losing the trauma is not the same thing as losing her. It’s not saying that she doesn’t matter; it’s not saying that any of the people we’ve lost don’t matter. Quite the opposite. It just says, it’s time to keep living. For them and for me.

Vulnerability needs a beat.

Oversharing is real. Sometimes it can be too much. If you’ve found you’ve done that, you might need to retreat for a moment or two; reassure the person you’re talking to that everything is okay. That you’re normal, you know? You can follow the template too. You’re safe.

Not forever. Just for a beat. Masking is overhead, after all.

And then on we go.

Those little paper condiment cups unfold to four times their size.

You know those little white cups from In-N-Out? You pull on their edges and they unfold and unfold. They’re surprisingly large! So much room for ketchup! Do you need that much ketchup? Maybe!

(You know about the secret menu, right?)

You will (almost) never regret being there for your family when things are hard.

I stood in Doctors, a real ale pub in Edinburgh that was never my favorite but was a short walk from the university buildings. I’d just presented at a tech meetup at the Appleton Tower, explaining to folks what Known did and why I thought the indieweb was important. I’d been back for a few days; I just planned to be in Edinburgh for a week.

Someone who I’d known for years — not well, just an acquaintance, but someone who I thought was generally smart and knew what they were talking about, more or less — was saying that she didn’t know why I’d left. “When they moved to California, they left you,” she said. “I would have said, ‘sorry, Mum, it’s your own fault.’”

I’ve played that conversation back in my head for years. At the time, I was so stunned that I didn’t have a real response. It was so far outside of my spectrum of values that I didn’t see it coming. Why would you say that to someone who had ripped their whole life up to be closer to their terminally ill mother? Why would you even think it?

I did do those things. When I was thirty-two years old, I moved to California for what I thought was a temporary visit. I ripped my life apart in the process.

When I was twenty-three years old, nine years earlier, my parents moved to California to be closer to my Oma. It seemed like a no-brainer. Of course you’ll be there for your family. We’re close. We love each other. We’ll support each other.

My move was a decision point: I didn’t know, exactly, where my life in Edinburgh was going. It could have gone to amazing places — and it also might not have. I knew that if I had chosen not to be with my mother during her illness, I would probably have regretted it. It was going to be seismic, but I needed to go.

But that person’s voice. I do think about it. If I’m honest with myself, it dovetails with my own middle-of-the-night anxieties. Should I have stayed?

I lost the person I was with at the time, who I hoped I’d spend my life with. That loss was devastating; the move itself was devastating. I loved my old life. But in comparison to not being there when Ma was struggling?

So, no. I did the right thing, even if I suffered a loss in the process. I’m grateful I was able to spend that time with my family. I was able to take Ma for walks and sit around the dining room table and give her hugs at the end of the day and help her brush her teeth when she was too weak to get out of bed. I was there. I am glad I was there.

Put the kids first.

If you arrange your parenting for your convenience rather than their well-being, they’ll feel it.

For example, I’ve found that if I get up as soon as he falls asleep, and he wakes up twenty minutes later to find himself in a dark room by himself, he’s scared in the moment, but trust has been eroded over time. Yes, eventually he needs to sleep by himself, but also, he’s three years old. There’s time. And I did it enough times that he now asks me, plaintively: “do you promise you’ll stay with me?” The first time he asked broke my heart.

I used to love traveling for work: when I was based in the Bay Area I’d go to New York City for long trips and love exploring in the cracks between commitments. I’d walk across the Brooklyn Bridge and find little shops in small corners; psychogeography the shit out of that place. And there would be all kinds of conversations I’d get to have as a result: meeting people for a coffee here, for a beer there.

But now I have a little guy who doesn’t understand why I’m going away, and who misses his daddy. It makes him nervous. He doesn’t FaceTime for long, but I’ve been told he’s obviously depressed when I’m not around. I still love traveling, and as he gets older I’ll find ways to bring him with me. But until then, I need to minimize the trips. I need to stay in bed and give him a hug. I need to spend the time.

Strict parenting is bad parenting.

When you set up high expectations and rigid rules, you’re not creating the conditions for a child to grow up into their own person. You’re effectively setting up a template and punishing them when they meander from it. Worse, you’re taking a still-developing human, who doesn’t understand their own emotions yet and hasn’t developed strong communication skills, and you’re ignoring the underlying needs and feelings that form the subtext of their behaviors. In a real way, you’re ignoring their humanity.

Having a child has taught me to look for the signs of sadness, of quiet worries, of not feeling well behind what a strict parent might call “acting out”. Every time he throws something or ignores something I ask him to do, if I remember to pause and really ask him about it, I’ll find that there’s something he isn’t saying — or at least, not saying with words. We can usually have a good conversation about it, and then a hug. It builds trust. He knows I’m looking out for him. I see him.

And then, of course, there are the parents who hit their children. That’s the version that’s unambiguous abuse. It’s a caveman approach to nurturing a human being that I think says a lot more about the emotional intelligence and capabilities of the parent than it does the child. They’ll often justify it in weird ways, by saying things like, “I was smacked and it never hurt me.” There often seems to be a kind of defiance to it. But guess what? Not being smacked would have hurt you less. I bet pausing for a beat and digging into how they feel would be revealing, too.

Parenting is hard. It can try your patience. But I can’t imagine hitting my child and wanting him to be anything less than his own person, free from everybody’s templates and expectations. Part of keeping him safe is keeping him safe from anyone who would seek to subjugate his spirit. And if anyone ever tries to hit my kid, I’m calling the police.

Walking fixes more than you’d think.

When I’m stressed, or feeling under the weather, or having trouble thinking my way around a problem, I’ve found that going for a walk is the best thing I can possibly do. It takes me out of my context, it allows me to blow off steam, and it puts me in a relatively isolated state where I have fewer distractions or inputs. It’s its own form of attention, in a way; its own way of being in the world.

It’s also really good exercise, particularly if you do it briskly: a 15 or 16 minute mile is a decent walking pace. As a bonus, it’s even better for blowing off steam at that speed.

My opinion: if you don’t live somewhere where you can walk outside easily, move.

Get that milkshake.

My trauma therapist and I have a shorthand: she tells me to get that milkshake.

What it means is this: sometimes it’s important to go do something nice for yourself. You don’t need to ask permission; you can just do it.

Life can be a lot. And I happen to like milkshakes. So sometimes, quietly, when I need a treat, I go and get one, guilt-free.

Cows are benign philosophers.

I think they have a lot more going on than they let on, is all I’m saying.

Don’t believe me? Talk to one. It’ll listen.

There used to be a cow field between my home and the center of town. I’d walk through it twice a day, stepping over the cattlegrid and dodging the cyclists who zoomed past. The cows were curious and friendly; they would come and investigate what you were up to.

There was another field that lay far below the Marston Ferry Road, back in Oxford, where I grew up. You could stand against the fence at the road and the cows would look up to see you. If you stayed there for long enough, they would congregate around you, as if you were the Pope. Perhaps they were hoping I’d feed them. I’d like to think they thought I might have something to say.

Optimize for community.

I’ve made two major moves in my adult life: once to California, and once, after my mother died, away from California, to the area outside of Philadelphia. It was lonely.

To have a friendship — a real one, not a warmed-up acquaintanceship — is to have built a non-romantic relationship where you really see each other. Neither wants anything from the other; there are no romantic or sexual expectations, or really expectations of any kind except that you’ll be there. It’s a relationship of shared support, values, and community.

Without it, you wither. People who don’t have friends die earlier. And while the internet can help you keep in touch with people you have moved away from, there’s no real alternative to having that mutual support there, with you, in the flesh.

But everybody moves. It’s not realistic to stay in the same place your whole life. People get jobs, family members get sick, people get priced out of their communities, there’s a Brexit. All kinds of things happen. So staying in one place is not a foolproof solution.

The thing, then, is to look for new places with community in mind. Where are you going to find like-minded people? Who are the people who see you now, and what kinds of places do they hang out in? Where are the comparable places in your new geography? Where are your people?

For me, that means finding the bookstores; the community spaces; the outsider arts events; the live music and the weird between-the-cracks culture. Find the people who don’t want to live to someone else’s template but do want to be kind. That’s where the good stuff is.

And given the choice between choosing a beautiful house in the middle of nowhere and a lackluster apartment in a place where you have community, I’d pick the place with community. It’s going to make your life better. It’s going to make everything better. Community cuts to the core of what life is; a house is just a house.

Culture is about the intersections between people.

My Oma taught me to cook. She loved to make food; often she’d be thinking about the evening meal throughout the entire day, regardless of whatever else was going on. In her nineties, she moved in with my parents, and although her love of cooking hadn’t diminished, her ability to stand over a stove had. So I helped her.

She was part-Indonesian, so the first dishes I put together started with spice mixes of turmeric, coriander, ginger, garlic, onion, and chillies. Indonesians call this the bumbu: a spice paste that can form the basis of many dishes.

You’re meant to make them with shallots, not onions. There’s supposed to be galangal rather than ginger; candlenuts are common. But those things weren’t easy to get in the San Joaquin Valley back then, so she made do. Sometimes she used milk instead of coconut milk; sometimes she couldn’t find ketcap manis. And it was always fantastic anyway.

You can improvise. You can use available ingredients. You can work with what you have and make the result your own, instead of trying for an unchanging perfect ideal. That’s how culture changes and ebbs and flows. I still make Indonesian meals, but they’re different to how my Oma did it, and the way I teach my son will be slightly different to how I learned. And so it goes, forever.

The important thing was the making and the eating, the gift of food and the sharing of it, not the verbatim copying of a version of a dish. There’s skill and craftsmanship in doing that, but that’s not where the life is.

Revisiting homemade food from your childhood is usually amazing; revisiting restaurant food from your childhood rarely holds up.

One was made with love, which still shines through the recipe; by following the same path, even if you substitute some ingredients you’re making it with love again. The other is just a product. The ingredients have changed over time; the portions are slightly different for business reasons; it’s missing the context and the smells. It’s generally better to let those memories sit.

If you have a fear of flying, playing The Muppet Show theme on takeoff really takes the edge off.

And post about it on the internet. Then, if something happens, people can point at your post, nod to themselves sagely, and say, “he died as he lived.”

I like the OK Go cover, for what it’s worth.

Show your working.

I remember taking my high school exams in the gym, individual chairs placed in rows atop wooden floors that smelled faintly of feet. You could hear breathing; the occasional cough; the squeak of rubber on hardwood as the invigilator roamed the aisles.

Showing your working was vital. Your answer to a math question could ultimately be wrong, but if your thinking was along the right lines, you’d pick up some points. They didn’t want to teach us by rote; they wanted to teach us how to navigate problems.

All of my best professional experiences have been derived from showing my working. When I started Elgg, every success was because we blogged how we were thinking about it; before we’d written a single line of code, before we knew we’d write any code, we’d talked about why it was important. People were attracted to the product, sure, but more than that, they were attracted to the ideas behind the project. And when we were wrong, they let us know — kindly. It helped us learn and grow.

That principle has continued to this day: to, in fact, you reading these words right now. Every time I share how I think, I make connections that I might not have otherwise. It’s helped me build community, land jobs I never would have landed, and find myself in rooms that would otherwise have been closed off to me.

The more you share of who you are, how you think, what you care about, and what your skills are, the easier it is for other people to find you, and for you to build connections and relationships. That doesn’t mean put yourself at risk: I’m not about to publish my home address here or reveal precise details about my kid. But there’s a lot you can say about yourself if you work in the open.

People join movements for different reasons. Not all of them are good.

In the early 2000s, a bunch of early web users, including me, wanted to tear down traditional gatekeepers: publishers who dictated whose voices could and couldn’t be heard, politicians who didn’t listen inclusively to communities, the traditional structures of power that maintained their own dominance, only including people who didn’t come from those hierarchies if they were deemed to be useful or compliant. So much of the early web movement was about creating a more participative world.

And then it turned out that some of those people saw an opportunity to insert themselves as gatekeepers. People like Mark Zuckerberg created vast companies that, in time, came to intermediate and charge rent for more than those old gatekeepers ever had. They sought to own aspects of our lives, like talking to our friends, that previously had been free from intermediation. The way for their companies to grow was to encroach upon the cultural commons. The gates they built became more and more powerful over time. As they calcified, some of them became templates that came to govern the rhythms and tenor of everybody’s lives.

Some did not. Others built the indieweb, and the free software movement, and found ways to undermine the control of these new gatekeepers. They stayed true to the values of the movement.

I tried to be one of them. Early in my career, I saw that ed-tech companies were milking giant contracts from tax-funded universities, while delivering software that didn’t do much to help people learn. Elgg was a direct response to this; it was fueled by a deep anger at the people who would seek to strip-mine a public good. Known, my second open source platform, was aimed directly at people like Zuckerberg. They were both attempts to undermine centralized wealth and power. That’s what drove me, and I have no regrets.

I have learned to look for the people who tear down gates for good, who try and foster new co-operative, participative movements in their place. They’re always there, even if they are not the most prominent voices in the room. And together, there’s a lot we can still do to make the world better.

Someone joining the movement for the wrong reasons doesn’t invalidate the movement. It just makes the work even more important.

To write, read with impunity.

Yeah, sure, read the “good” stuff. I love literary fiction. The Color Purple is my idea of a perfect novel. I just finished I Who Have Never Known Men, which is an astonishing novel that plumbs the depths of what it means to be human, written with poetry.

But you can read whatever you want. All inputs are worthwhile. Pulpy airport thrillers have brought me through some hard times. Fan fiction has struck a nerve that I never knew existed. Some of the most well-crafted writing I’ve ever read was published on a style-free website, tumbling onto the page in 12-point Times New Roman. It’s all good. All of it.

If you want to write, the only imperative is to read.

That’s certainly true for my long-form writing, and that might be advice you’ve read before. But it’s true for my short-form writing, too. If I haven’t dug into a book lately, my blogging suffers. Even my writing at work — emails and process documentation are hardly the bastion of literary prowess at the best of times — is less inspired.

Read voraciously. It’s fuel.

Fight for the relationships that matter.

“There are other fish in the sea,” the aphorism goes. But when you’re in a relationship where things aren’t going perfectly, I think it’s better to assume there aren’t.

I don’t mean that you should stay in an abusive or untenable situation. If you are being harmed and there’s no chance of living in harmony, then, absolutely, you need to get out of there. But if it’s just not quite right, or if circumstances have become obstacles, I think there’s a lot to be gained by fighting for it. At least until you’ve determined that there’s no possible way forward.

This is where, in my life, not showing up for myself has sometimes allowed me to fall into a defeatism that has caused me to give up early. “Of course this won’t work,” I think to myself. I’m the through line to the failure. I shouldn’t assume that someone would want to be with me. They’ll be better off without me.

The result is giving up on people who really care and situations that could last a lifetime. It’s not a given; nothing is. But there’s a real scarcity to people that are really compatible with you. (Or, I should say, there’s a real scarcity to people that are really compatible with me.) So, while it’s worked out for me in the end, I have sometimes wished I would have fought harder, and not assumed that eventually everyone will want someone better.

I don’t think you can show up well in a relationship without assuming it’s the only relationship on earth that will ever be important to you. It’s got to have fire. It’s got to have stakes.

It’s got to matter.

And if you give up without fighting for it, it doesn’t.

Make the dumbest jokes imaginable.

Q: Why did Pierre-Joseph Proudhon only drink camomile tea?

A: Because all proper tea is theft.

C’mon!

You contain multitudes.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

A single person holds many conflicting identities, roles, beliefs, and experiences; our selves are complex and ever-changing. There is no singular, static definition that we can use to capture any person.

We’re not making art or building a business, because there’s no way to separate the self cleanly into those categories. We’re not our professional titles and our personal contexts, because those things are inseparable. We have no way of surgically extracting pieces of ourselves, or freezing them and framing them, unchanged. We’re always learning, always growing, always making connections between the things we know, the things we’ve felt, our flaws, our traumas, our successes, our pride, the things we’ve done and haven’t done. In everything we do and everywhere we are, we are all of ourselves.

When we build walls, we build overhead, and we keep building overhead until it’s impossible to maintain and it all comes tumbling down. A single cave’s shadows can’t capture a whole person.

Better, then, to understand that we are our whole selves, and to respect that in ourselves and in the people around us. We are smart and brave and silly and stupid. We are strategic and impulsive. We must be allies for each other. In a world where we are asked to refine ourselves down into digestible metadata for the benefit of machines and algorithms, we must celebrate our full humanity.

Bring your full self to work. Bring your full self home. Only when we’re allowed to be intact, with a community built on mutual sight and support, can we live sustainably: our overheads manageable, our wounds tended to, our victories celebrated.

And we all deserve to live sustainably. We all deserve to be supported. We all deserve to be well. We all deserve to live with our full, changing, contradictory identities out in the open, unmasked.

So let’s.