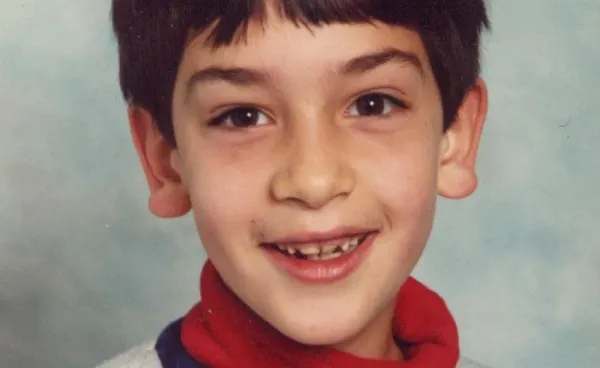

The Zurich protocol

They came for the newsroom. It was ready.

Things I've learned.

Building a community means looking beyond coding tests.

Highlights and hopes for the new year.

They came for the newsroom. It was ready.

Things I've learned.

Building a community means looking beyond coding tests.

Highlights and hopes for the new year.

Personalization is coming to journalism. The question is: who controls it?

The future of the web depends on simple, open standards.

Ben Werdmuller explores the intersection of technology, democracy, and society. Always independently published, reader-supported, and free to read.

They came for the newsroom. It was ready.

"The truth is that prestige journalism is lousy with Bari Weisses, up and down the line. Ask any journalist trying to cover the genocide in Gaza or the social death of gender nonconformists."

"But these questions are framed in this way to encourage us all to aspire towards roles that enable us to do our best work, to have the biggest impact, and to live according to our values."

Things I've learned.

Building a community means looking beyond coding tests.

Looking ahead: humans are cool again.

"Instagram no longer believes it can beat AI by making more or better content. It wants to be the referee, to decide what is real and what is not, and to build systems that can do it at scale."

Simon Willison breaks down what happened in the LLM space in 2025. Some of it has the potential to transform tech forever.

This year's predictions from tech experts and decision-makers are notably pro-human.

"Notes from someone who's withstood White House demands to stop an explosive story—and who once even had a 60 Minutes piece spiked."

A way to build a habit out of what's important.

Highlights and hopes for the new year.