Building distributed media for a democratic breakdown

Preparing viable alternatives for broadcast censorship and a restricted internet.

Jimmy Kimmel returned to the air on Tuesday and delivered a 28-minute monologue that set the record straight and sharply criticized the Trump administration. Sinclair and Nexstar, two TV networks whose affiliate stations collectively represent 25% of ABC’s broadcast audience, refused to transmit the show, pre-empting it with extended news programming instead. Trump, who is only increasing his authoritarianism, took to Truth Social to threaten ABC with new legal action for bringing it back.

Someone needed to introduce them to the Streisand effect: his monologue was streamed over 17.7 million times on YouTube in the first 24 hours alone, breaking records in the process. In the age of the internet, broadcast television is a legacy technology, and the content can always be obtained elsewhere. The median age of a primetime ABC viewer is 65.6 years old. Everyone else is streaming.

While the discussion of Kimmel’s week-long indefinite suspension dominated media discourse, a few other things were going on. New Jersey public media announced it would cease operations due to funding cuts. Cascade PBS in Seattle announced it would stop producing written journalism. Arizona public media made significant cuts to its content production staff. And on, and on, and on. Public service media has been gutted by the defunding of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and other attacks. It’s maybe not as exciting as the former host of The Man Show being canceled for a very mild criticism of the current administration — which, to be clear, is an alarmingly fascist abuse of power — but it’s ongoing and harmful. It leaves rural communities in particular with no information sources and no meaningful journalism covering their local governments.

If you believe that public service journalism is a load-bearing prerequisite for democracy, as I do, these are scary changes. These changes are particularly alarming because they're happening just as the news industry overall has been contracting for decades, leaving fewer resources to fill the gaps. Other, larger, newsrooms could theoretically help fill the content and funding gaps, but there are fewer and fewer resources to share around.

The irony is that local news is the one place where this erosion of trust hasn’t been happening: local newsrooms know how to build community and are disproportionately trusted as a result. It’s also the one place where the broadcast medium is still important; in an emergency, or in a broadband desert, a radio signal can be the last source of real information. You can’t, yet, take a closed rural station and move it to YouTube without losing a large proportion of its audience. Around 90% of Americans have access to broadband internet, but that last 10% really matters.

Of course, if all the shuttered public media stations did move to YouTube, the government would go after that, too. As a service owned by a single corporation, it’s a central point of failure. Publishing on the open web would remove that risk, but the internet itself has been repeatedly under attack. In some areas, legislation has passed that effectively bans certain kinds of content (Bluesky is unavailable in Mississippifor this reason) and net neutrality has been decimated nationwide, making it far easier for an ISP to cut access to a particular service, perhaps in response to pressure from the government. With the government flexing severe restrictions to broadcast media, and nothing stopping severe restrictions to streaming media, there’s nowhere left for information to go.

In Cuba, the internet was legalized in 2019, although you need a permit to have a home connection, and connection quality is still intermittent. Starting long before that, people with access would download content to flash drives and then distribute them through a vast, illicit network called El Paquete Semanal, or The Weekly Package. You could think of it as a magazine: every week there would be a new issue of media that couldn’t be obtained any other way. It became so popular that the government tried to release its own competing USB drop containing approved media; unsurprisingly, it didn’t catch on.

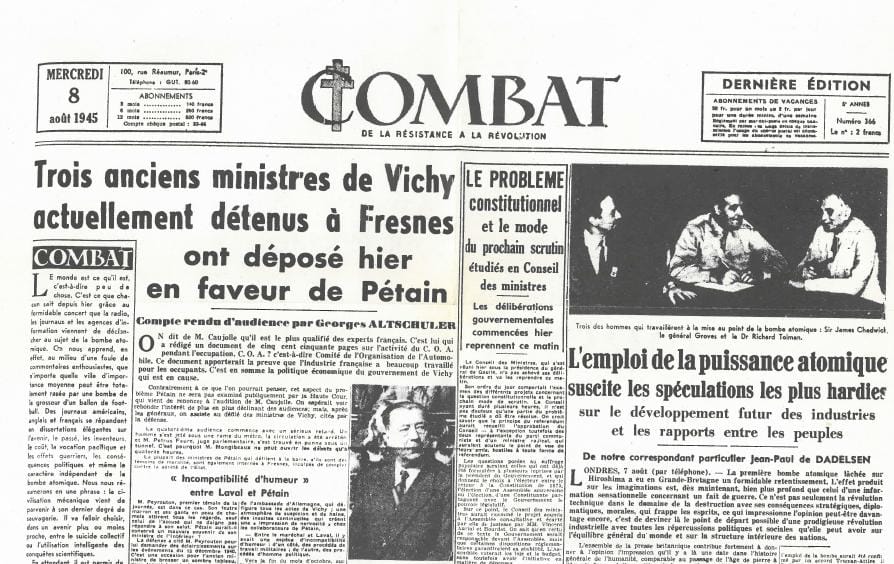

There are other analogues through history to draw on: Samizdat was a method for reproducing and distributing censored material by hand in the USSR; its network was similarly decentralized. In France during the Nazi occupation, there were over a thousand underground publications operating with portable printing equipment and distribution cells, with over two million copies circulated in total.

We’ve become very reliant on the internet, but we may need to prepare for a post-broadcast, post-open-internet era. Ironically, newspapers, long the poster-child of media’s death throes, are semi-distributed and would be more resilient to this more restrictive media landscape, as the French resistance example demonstrates. (Of course, a newspaper that relies on a centralized printing press can always be shut down.) These are things that might happen, not things that definitely will, but it doesn’t hurt to consider this as a potential future that we might need to react to.

In a world where we succumb to truly authoritarian control over the media, I think there may be something to learn from El Paquete. A discrete bundle of digital media can be transmitted in multiple forms. It can be accessed via the web; consumed via an app that downloads the new bundle every week; transmitted over peer-to-peer networks; stored on resilient alternative file systems like IPFS; and even through sneakernet networks like Cuba’s. The bundle could contain archives of entire websites in the Internet Archive’s WARC format, downloads of video podcasts, and so on, linked with a web-based interface that would be somewhat akin to a DVD menu.

Such a bundle would probably not be collated inside the US. Instead, a group might be established in safe third-party countries like Switzerland, who could communicate securely with journalists on the ground in the US and elsewhere. They would bundle the release, publish it to various networks (the open social web, IPFS, p2p networks), publish a checksum hash, and publicize it in Signal channels.

It would be paid for in various ways. The central newsroom would need to be funded by international non-profits oriented towards re-establishing media freedom in the US (for example, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders). Individual journalists and creators in the US would need to be supported by communities more local to them and would likely take the form of mutual aid as much as direct support. Because traditional payment and crypto networks are both highly traceable, direct donations or subscriptions might not be feasible or safe.

I think it’s important to establish this ahead of time. By the time the internet is locked down and major restrictions have been applied to broadcast media, it’s too late. The good news is that it’s kind of cool in itself: the form of an online magazine that carries submissions from multiple news and media creators has a lot of scope for experimentation at every level, from content to design. It’s offline-first, which means you can interact with it on a plane and in other situations where internet is not an option. That’s neat in itself!

It also solves the problem of how this would be found by new readers to begin with. After a democratic collapse, discovery would need to be through word of mouth; before it, though, such a product could be promoted through more traditional channels (emphasizing the innovative nature of its issue-based format rather than its resiliency to authoritarian control). Early adopters who are attracted to the initial product would form the backbone of the word-of-mouth network later on. Just as newsrooms today thrive if they successfully build community, building trusted networks of people becomes vital for distributing underground material in an authoritarian environment. Historical underground media networks took years to establish, as all communities do; building community would need to begin immediately.

Our entire software stack — our content management systems in particular — are designed to be accessed through a functioning internet. Luckily, thanks to tools created by organizations like the Internet Archive, we can simply build websites locally on our own devices and create an archived version to distribute. The tools are there; the work to be done is all at the human level.