Tintin and the fascists

As a child, I freaking adored Tintin, the Belgian comic strip about a boy detective and his little white dog, Snowy. There was something intoxicating about the mix: international adventures, a growing cast of recurring characters, conspiracies, humor, hi jinx. Even the ligne claire style of drawing — cartoonish figures on more realistic, epic backgrounds — lent themselves to a feeling of scale. It heavily informed my childhood imagination, far more than other comics might have. I was into the French Asterix comics as well as American Marvel and DC offerings, but Tintin was the real deal.

Of course, it was also hyper-colonialist, and the early entries in particular are quite racist, although as a seven and eight year old, I didn’t really pick up on those threads. Tintin in the Congo goes exactly as you might expect a Belgian strip about the Democratic Republic of the Congo written in the 1930s (when it was fully under extraordinarily harsh Belgian colonial control) to go. The Shooting Star’s villain was originally an evil Jewish industrialist, and the story (written in 1941-2) even carries water for the Axis powers and originally contained a parody of the idea that fascism could be a threat to Europe. That, too, went completely over my head.

I hadn’t realized until recently that Tintin originated in a hyper conservative, pro-fascist Belgian newspaper, and continued in another conservative newspaper that freely published antisemitic opinions under Nazi occupation. The first story, which I’ve never read and wasn’t made as widely available, was a clumsy propaganda piece against the Soviet Union, and it carried on from there.

This isn’t a situation where the author’s views can be held as separate to the work. It’s all in there. Even though Tintin enters the public domain tomorrow (alongside Popeye, among others), I don’t think the right thing to do is to salvage the source material.

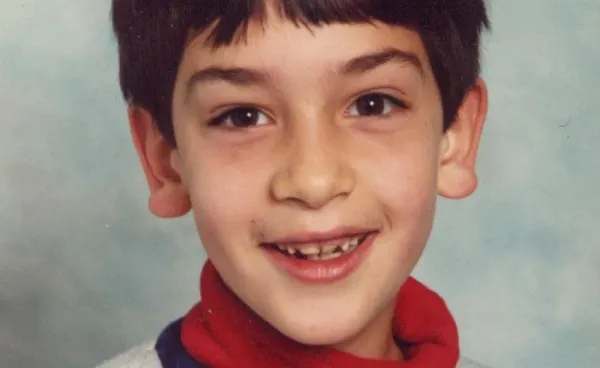

Which leaves a missing space. I loved those adventures, and I’d love my son to have something similar to cling to. Superhero stories aren’t it: although there’s some supernatural activity in Tintin (and aliens in one later story!), the threats and ideas are very tethered to reality. It sits in the same zone as James Bond — another colonialist relic — but unlike Bond, Tintin is just a kid. He doesn’t have the weight of the British intelligence establishment behind him. He’s got a dog and an alcoholic sea captain. There’s something infectious about that comedic, adventurous, dysfunctional dynamic.

I’d love to see new stories, with new characters, that share Hergé’s aptitude for compelling globe-trotting adventure but leave aside the outdated ties to colonialism and fascism. There are stories to be told that lean into international imbalances in a positive way: discoveries about how greedy businesses have exploited the global south, or mysteries that turn modern piracy on is head to reveal that it’s not exactly what we’ve been told it is, or the businesses and people that are profiting from climate change. Tintin had stories about oil stoppages in the advent of a war and a technological race to the moon: these sorts of themes aren’t off topic for children and can be made both exciting and factual. The global backdrop would gain so much from those ligne claire drawings and a sense of humor.

It’s not something Marvel or DC could do, with their heightened, muscle-bound heroes and newfound need to be ultra-mainstream. It’s also not something that I’ve seen in other graphic novels for children. But there’s a market there, left by the Tintin hole, and I’d love for someone to fill it.