Why the open social web matters now

The needs are real – and you have so much power.

I was privileged to deliver the opening keynote at this month's FediForum, a conference for people building and supporting the open social web. My talk touched on what's happening now, drew on my experiences building Elgg and Known and investing at Matter Ventures, and gave participants three important questions to ask themselves as they build platforms and serve communities.

Here's the talk in its entirety, courtesy of FediForum. The transcript follows below.

Introduction

If we haven’t met, my name’s Ben Werdmuller. I’m based just outside of Philadelphia.

Today, I’m the Senior Director of Technology at ProPublica, a non-profit newsroom here in the US that investigates abuses of power and betrayals of the public trust by government, business, and other institutions. If you remember the Clarence Thomas corruption scandal, Project 2025 co-author Russell Vought’s private remarks about how he was going to go after the left, or Peter Thiel’s tax-free investment scheme, that was our reporting.

I’m not a journalist but I’m very proud to support the people doing this journalistic work.

But I actually started my career by building open source social networking platforms. I built a platform that allowed communities to self-host on their terms, using exactly the features that would support their needs. Elgg started in higher education, but it was used by NGOs like Greenpeace and Oxfam to train aid workers, it was used by the anti-austerity movement in Spain to help them organize, and Fortune 500 companies and at least one government used it as their primary intranet.

We always wanted Elgg to federate. That was the plan from day one. It was an obvious need. There was no ActivityPub yet. We picked up on whatever tech we could — OpenID, Friend of a Friend — but ended up trying to cobble our own standard together. It wasn’t ActivityPub, and it didn’t work out quite as we’d hoped, but it began to touch on some of those underlying ideas.

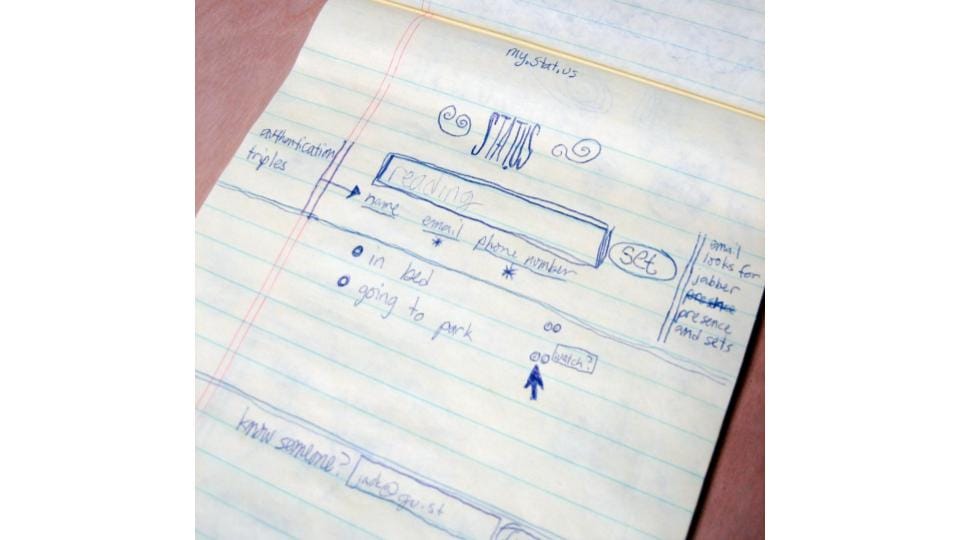

I built Known as a way for anyone to build feeds containing content of any type. It was mostly used by indie web bloggers, and it supported indie web standards for decentralized conversations, but it could support any number of users, and a feed could be published to by webhook and micropub, meaning theoretically any automatic system could post there.

I led west coast investments for something called Matter, which supported early-stage mission-driven startups.

These were all ventures with the potential to create a more informed, inclusive, and empathetic society. That was our hypothesis. They had diverse teams and missions that weren’t a million miles away from the missions of people in this room.

And then I took a hard left turn and moved into leading technology for newsrooms, because I felt like that was the best way to be useful in this era.

The 19th reports at the intersection of gender, politics, and policy - a much-needed inclusive newsroom in a world where much of our news is produced by white men in New York City. And I’ve already introduced you to ProPublica.

So I’ve been involved in building platforms, supporting people who are building platforms, and leading technology in the kinds of organizations that we hope will be platform users. I’ve been on all sides of the table.

And now, maybe ironically, while I’m not building or supporting platforms, open social networking is finally taking off. My timing has always been terrible, but I’m thrilled to be back in this conversation.

Why should anyone care?

I’d like to open FediForum with this provocation:

Why does this matter? Why should anyone care about decentralized or federated networks?

Let’s start by examining the moment we’re in.

Here in the US, our government is becoming increasingly authoritarian.

Immigrants are being ripped off the streets by masked officers without due process and often shipped to places like El Salvador or South Sudan. Just last week, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth told a roomful of American generals that he wanted them to fight “the enemy within” in the United States, echoing a phrase used in Nazi Germany.

In Gaza, a UN commission found that there is indeed an ongoing genocide in progress. Many tens of thousands of people have been killed. Some of them were allegedly identified by a targeting AI through metadata from their WhatsApp chats.

Here in the US, students and journalists who have described it as a genocide have been detained or deported. Even liking a post on Instagram has been considered an actionable signal that you support terrorism by aligning yourself with Hamas.

And on some US-run social networks, people from Palestine who have been asking for help have been systematically removed.

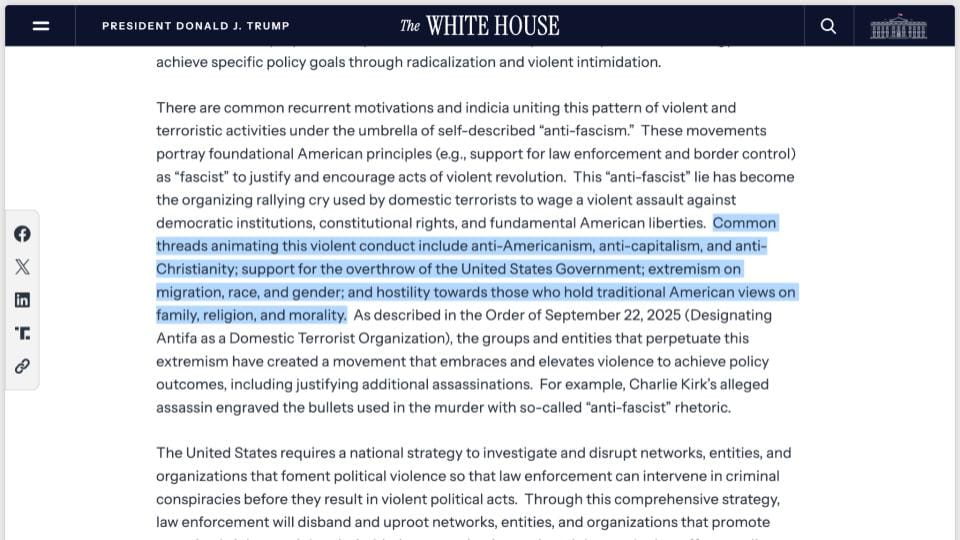

National security policy now describes the following amongst signals that you might be a terrorist:

“anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, and anti-Christianity; support for the overthrow of the United States Government; extremism on migration, race, and gender; and hostility towards those who hold traditional American views on family, religion, and morality”.

People from communities that were already vulnerable - trans people among them - have been explicitly targeted, just as they were in 1930s Germany.

And speaking of trans people, they’re reportedly about to be classified as a nihilistic violent extremist threat group.

Categorizing these communities this way is a pretext to surveillance.

The CLOUD Act, passed in 2018, compels US-based online services (including US subsidiaries of foreign organizations) to share data with the US government regardless of where in the world that data is stored, and regardless of local regulations like GDPR. In the event of a criminal subpoena, including for suspected terrorist activity, you may never know your data was supplied.

That was always creepy, but in a world where you may be profiled as a potential terrorist for having left-of-center opinions, or for being a member of a vulnerable group like the trans community, that really matters.

The capitulation of social media

The first step towards doing something about these events and threats to democracy is to know about them. How do we learn about them?

In most western countries, social media and video networks are now our main source of news and the way we receive updates from our friends. A handful of companies own how we learn about the world, giving them the ability to shape our collective worldviews, influence movements, and prioritize their own interests.

They have never been great actors — Amnesty International accused Meta of platforming a genocide in Myanmar in 2017 — but their influence and power has never been greater than it is today.

And every major commercial social network is complicit. They’re collaborators.

We all know about Twitter acquirer Elon Musk, who bent the platform to fit his political worldview. But he’s not alone.

Here’s Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, owner of LinkedIn, who contributed a million dollars to Trump’s inauguration fund.

Here’s Mark Zuckerberg, who owns Threads, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, who said that he feels optimistic about the new administration’s agenda.

And here’s Larry Ellison, who will control TikTok in the US, who was a major investor in Trump, and who one advisor called, in a WIRED interview, the shadow President of the United States.

Social media is very quickly becoming aligned with a state that in itself is becoming increasingly authoritarian.

The decline of journalism

Journalism and the media is a way we’ve traditionally learned about the world. And a free press is usually a check on power. Multiple studies have found that communities with an active newsroom have less political corruption - or, rather, that communities without an active newsroom had more corruption.

But the news industry failed to adapt to the more personal nature of the web, and has been in slow decline for many years.

Compounding this, business decisions by companies like Google have led to fewer clickthroughs to news sites from search engines as well as from traditional social networks. They display AI summaries and show you answer boxes instead of prominently linking to the sources themselves.

Fewer people clicking through translates to fewer pageviews, fewer subscribers, and fewer donors. Engagement and revenue are both declining. Public service journalism is withering just when we need it most.

And now public media has been defunded by the government, driving the final nail into the coffin for many outlets. Hundreds of them have closed or are predicted to close soon.

Between the capitulation of social media and the slow decay of journalism, the result is less sunlight, more corruption, and more freedom for authoritarianism to spread and thrive.

The problem is global

I’m speaking from the US context, but these aren’t US only problems. For one thing, America’s influence extends worldwide, both through agreements and through overarching legislation like the CLOUD Act.

For another, there are parallel movements elsewhere. Over in Britain, a nationalist movement that started with Brexit is taking hold, while public journalistic institutions like the BBC are under threat. The Online Safety Act requires identity verification that can put people in vulnerable communities at risk, and the government seemingly continually asks for backdoors in privacy software. Similar patterns are emerging over much of Europe. Japan just elected a far right prime minister.

There’s a lot going on everywhere. It can be overwhelming.

And whether you like it or not, sitting in this virtual room, you’re the counterculture. All of you are building platforms, communities, and relationships, with the potential to create an alternative to this centralization of power and influence.

Social media and social networking

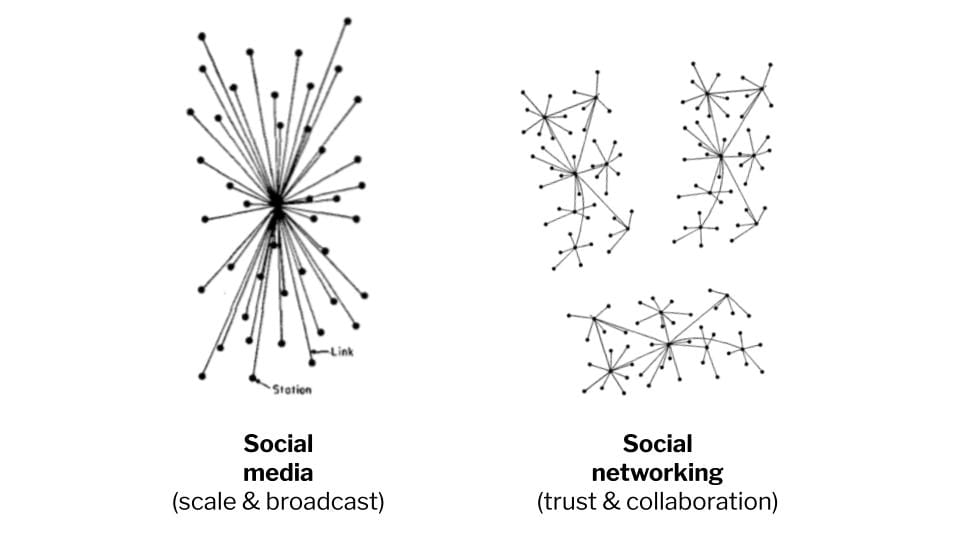

We talk a lot about social media these days, but I want to register two definitions with you. Social media is the town square: a global commons where we can all learn from each other and build audiences at scale. Social networking, on the other hand, is a way to support communities of any kind using technology. These two things can interact and intersect, but they are not the same.

Because of its emphasis on scale, I think social media is more predisposed to centralization, and because of its emphasis on relationships and communities, social networking is more predisposed to decentralization.

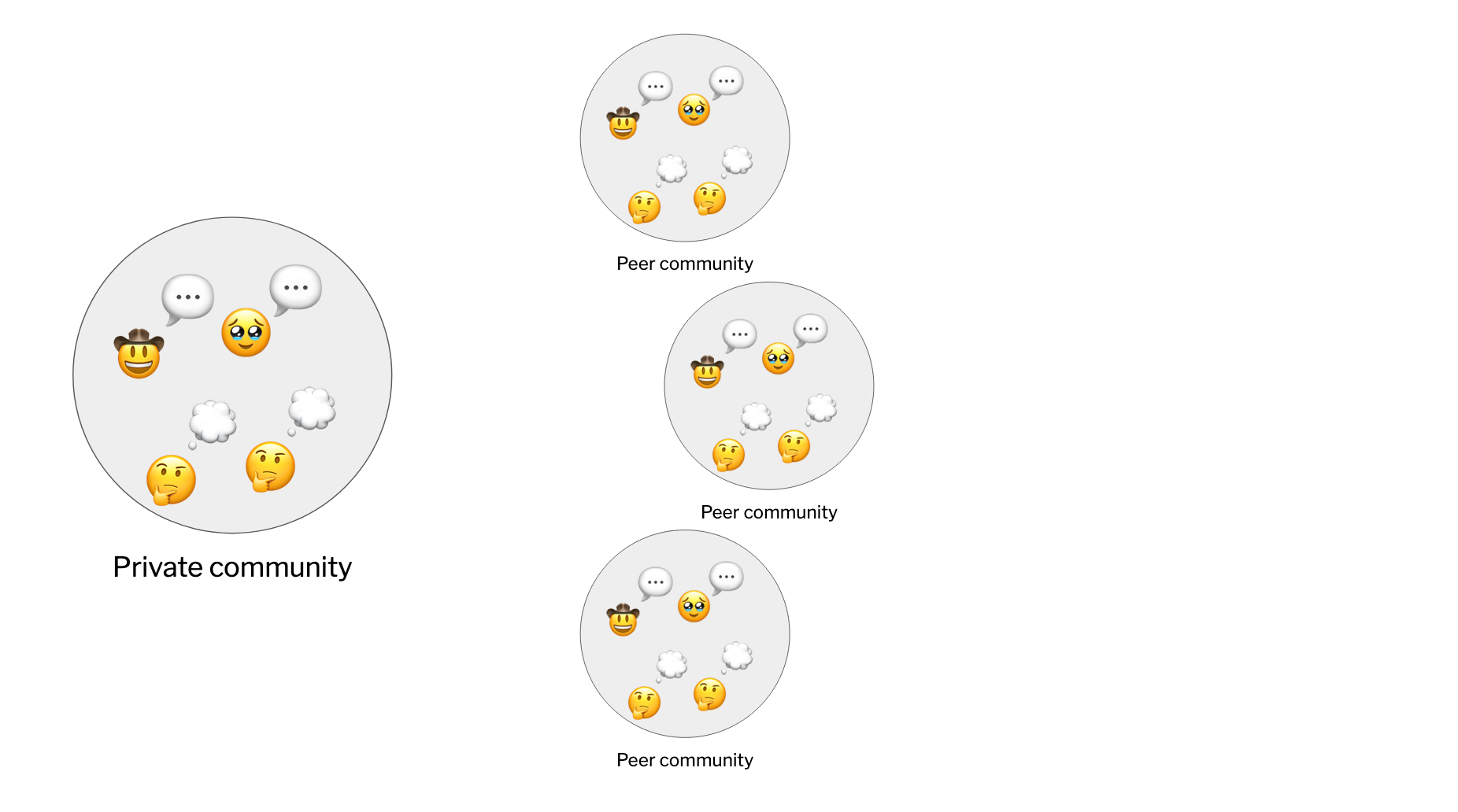

Let's make this more concrete. Imagine I'm part of a rapid response network protecting immigrants from deportation without due process.

I have a core community. We trust each other completely. We coordinate the sensitive stuff in our private space: who has access to various resources, which volunteers are trained legal observers, how we move money to families when someone gets detained.

This inner circle needs to be absolutely secure. These conversations could get people deported if they fall into the wrong hands.

But our community can't cover a whole city. So we connect with other groups we trust: other mutual aid networks, immigrant rights organizations, faith communities that have offered sanctuary.

These groups have their own secure spaces, their own trusted circles. But we need to coordinate with them. When ICE shows up to detain someone, we might need bodies there within 20 minutes: witnesses with cameras, legal observers, community members who can slow the process down and ensure due process is followed.

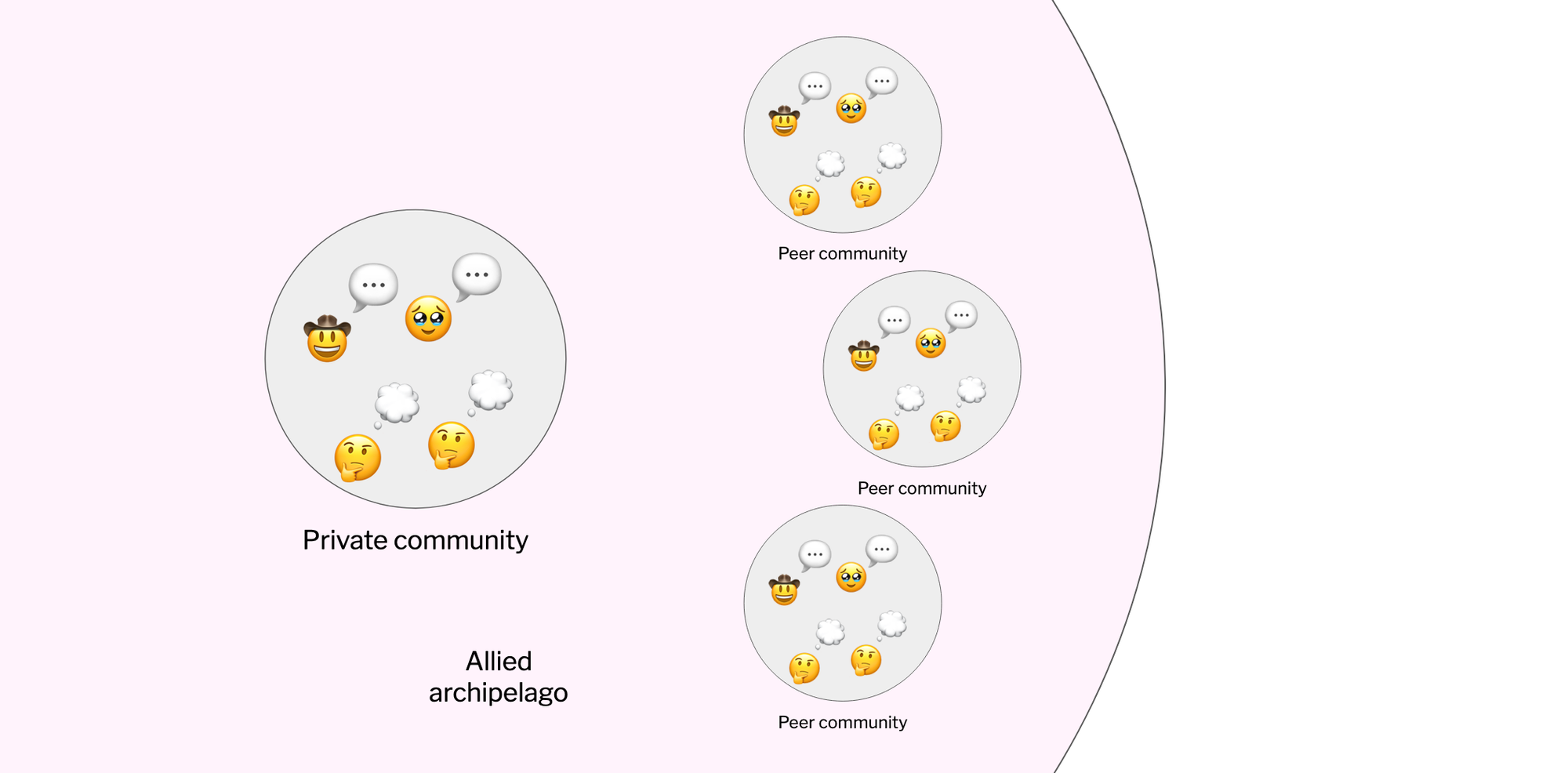

We're building an archipelago of trusted communities, each with their own secure space, but able to communicate across those boundaries.

Together, across this archipelago, we can have private, end-to-end encrypted conversations about who's available for rapid response, where ICE was spotted this morning, which families need emergency funds.

This encryption is vital. Without it, the web hosts that power our communities can be subpoenaed without our knowledge, and our conversations can be handed over to the government, putting everyone we're trying to help at risk.

So at this level, everything must be encrypted. The inner circles and the archipelago both need to be surveillance-proof.

Federation makes us stronger. If one community is compromised for any reason and is taken offline, the others remain online. Just like the web itself.

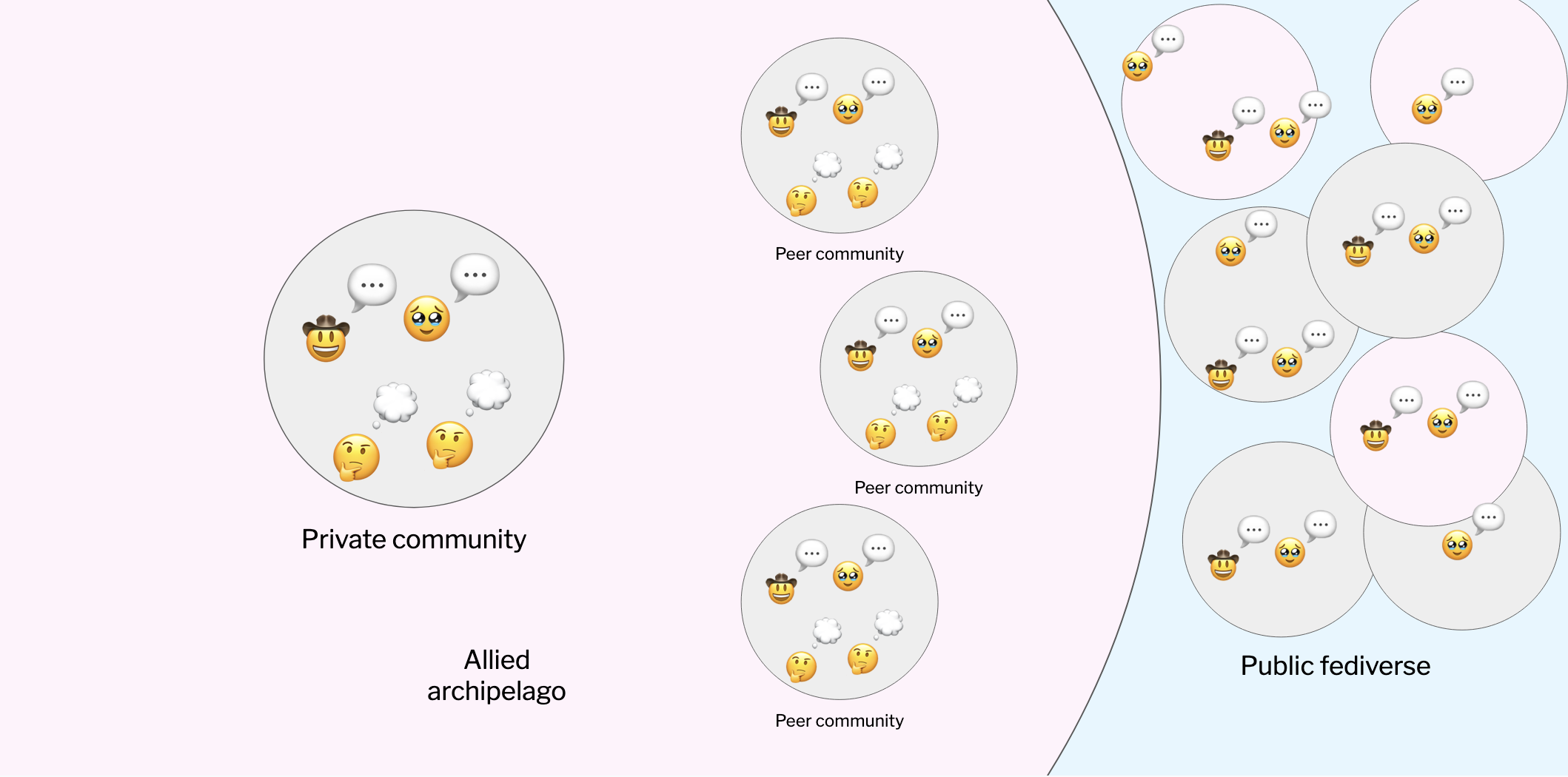

And when we're ready, then we step into the public fediverse.

We announce the action. We share the video. We name the officials responsible. We rally public support. Everyone has access to this: it's the town square, the place where we build power at scale.

But we only got here safely because we could organize privately first.

That's the distinction: networking builds trust and enables coordination within and across communities. Media scales that message to everyone.

And the fediverse can do both. And it can do it without centralization, without being subject to any one company’s business decisions, and, if we add encryption, with freedom from surveillance. For vulnerable groups in particular, that provides a refuge, a place to build relationships and community, and, perhaps most crucially, a place to organize.

But these two modes - social media and social networking - are different modes with different use cases and different technical requirements.

In my example, each group hosts its own communications and controls its own data. They federate to form an archipelago with other trusted groups. At both of these levels, communications are end-to-end encrypted because they have to be. These conversations can’t happen safely without it being physically impossible for adverse actors, including the government, to obtain access to them without the active participation of the community itself.

The fediverse is not inherently safer because it’s federated: an open, permissionless protocol can be exploited just as easily to surveil as it can to build.

But then, at the public level, those same groups can broadcast to the open fediverse when they need to.

The spec for MLS over ActivityPub covers these activities, and using it within a limited archipelago limits potential exposure to a set of trusted communities. Most fediverse platforms don't currently support this archipelago model. But the building blocks exist.

Start small

Of course, this isn’t limited to immigration protests or even activism. This model of small, trusted communities that intersect with the public sphere is already at the heart of the open social web. With the right tooling, it has applicability for journalism, for mutual aid, for co-operative culture, for collaborative marketplaces, and for every aspect of public life. The open social web is, I believe, and I know I’m preaching to the choir, the future of social and the future of the web.

So you might reasonably disagree with me about the threats, the needs, and this particular manifestation of a solution.

But my point is not necessarily to advocate for this particular model. It’s when we’re building something new, we need to start somewhere small and specific.

We need to start by supporting a specific community’s burning needs really well and grow outwards from there.

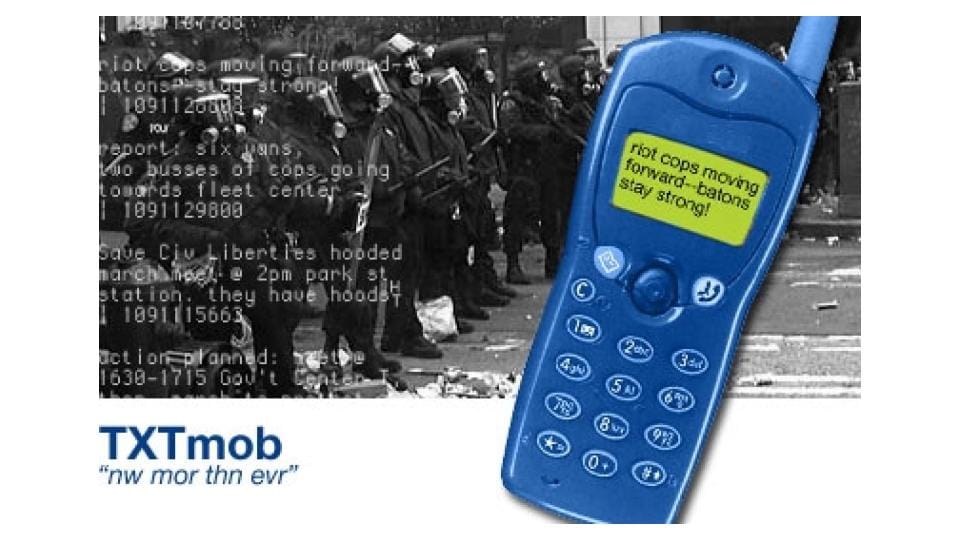

Let's talk about TXTmob.

TXTmob was an SMS messaging service originally built by the Institute for Applied Autonomy for protesting political conventions in 2004, towards the beginning of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Activists used it to coordinate actions, report on police movements, and share their whereabouts. A user would send their status update via SMS, and other members of the group would receive it. They refined it based on this very specific use case.

After the Republican National Convention, there was a weekend session of hackers and activists. Two of the people there - Rabble and Blaine Cook - worked for a company called Odeo that was having trouble getting its social network for podcasting off the ground. They made some helpful suggestions that improved TXTmob, but they also did an internal presentation at Odeo about the tool and how it worked.

A few days later, at an internal hackday, the team there prototyped a tool that worked very similarly. Eventually, they named it Twitter.

All of our microblogging tools have this lineage: short messages designed for a specific group of people and limited in length for a specific reason that was an outcome of that use case.

A specific use case led to a working prototype that led to a wider application. That pattern is repeated again and again.

Helping communities today

For the open social web to thrive, we need to go back to real communities with real-world use cases and solve their problems better than anything else. Not the needs of individuals within them, but of the interconnected communities themselves. We need to build social networks that deeply support their needs, and then social media that helps them thrive.

So if microblogging emerged from SMS updates for activists coordinating at the RNC in 2004, what should emerge from the needs of communities in 2025?

What does that look like in practice?

I'd challenge anyone looking to start a new platform - or add features to an existing one - to ask three questions.

First: Who specifically do we want to help?

Not "activists" or "journalists" in the abstract. Which organizers? Which newsrooms? Which communities?

Have you sat with them? Marched with them? Watched them work? Have you understood how they communicate and where their current tools fail them?

Second: Why are we the right team to help them?

Is it lived experience in that community? Deep domain knowledge? A unique technical capability they need? Or are you building what you find intellectually interesting, rather than helping someone?

If your team isn't representative of the people you're trying to help, you might not be the right people yet.

Third: How can we address their needs better than anything else that exists today?

I don’t mean ideology. Open source or federation are not solutions in themselves. They’re characteristics of a solution.

We need to be concretely meeting needs. Not what you think their needs are or what they should be, but what you’ve learned they are from getting to know them deeply.

What specific pain point are you solving that keeps people on WhatsApp despite the surveillance risk, or on X despite the white supremacy?

What does open source or federation make possible that concretely makes their lives better today? Is it really better than Signal or email or whatever else they’re using?

Concepts like "credible exit" are hypothetical. They matter in the long term, but they won't drive adoption today if the immediate experience isn't better. What’s making their lives better right now?

It might be that you don’t have the answers today.

Even then, there’s so much you can do. Maybe your role is to provide infrastructure, funding, technical support for communities building their own solutions - or just to promote the movement and spread the word. Maybe it’s about supporting and contributing to other projects in forums and communities like FediForum. Maybe you need to build your community or a team, building relationships and doing research until you do have the answers.

But I don’t think any social movement, any community, needs saviors riding in on a white horse.

The world particularly does not need more tech teams swooping in to change the world from the basis of their own assumptions, even if they do believe in open source or federation. It needs more people willing to listen to the people who know, and to support people who are already on the ground.

These questions work.

At Matter Ventures, I invested in and supported a portfolio of 75 startups, all of which were mission-driven, trying to make the world better in some key way. It taught me a lot about projects and how they succeed or fail.

It turns out these questions for mission-driven open social web teams happen to be the same ones that most closely predicted whether one of those companies would live or die.

If a team was trying to be the smartest people in the room and invent a solution without knowing, being of, and co-creating with the communities they were trying to help, they were not likely to succeed at what they were doing. The startups who were led by unwavering visionaries who thought they could invent something amazing because they were smart and clever and creative, with better values, were the ones that died fastest and hardest.

If, on the other hand, they did the work to understand their communities, make sure they were building something that really served them, made the effort to grow to be representative of them, and changed their focus when they learned that their communities needed something different to what they had in mind - those teams were much more likely to succeed.

I realize most of this room probably doesn’t care about startups.

But again, not to belabor the point: the same questions that predicted whether mission-driven startups would succeed apply to everyone building on the open social web. Who are you building for? Why are you the right team? How does your solution concretely serve their real human needs better than anything else?

I’ve learned this first-hand.

I mentioned my two social networking projects, Elgg and Known. Elgg started with a concrete use case in higher education, then expanded to adjacent use cases in non-profits, and then to businesses and startups. It became a thriving business for years. Investors came to us asking to put money in. Several governments used it as their national intranets.

Known was designed for the indie web, and had a community of people who were lovely people - they’re all my friends today - but they liked and supported us because of a certain set of shared values that we were in line with. It was ideological. There was no concrete real-world use case and Known had real trouble building traction.

The internal newsroom conversations I’ve had about the open social web have been disappointing to someone like me who cares about the space. They want to know why it’s better for their bottom line than the incumbent social networks that they already know how to measure and use. The answer can’t be ideological. There are real answers - people on the fediverse are more likely to engage in and donate to journalism, for example - but stories about how the fediverse is decentralized don’t land for them. It doesn’t speak to their needs.

It turns out that if you solve a community’s needs deeply, you’re valuable to them. And these communities have intersecting communities, which you can get to know too, and be valuable to also. You’re more likely to reach sustainability, whatever your model is, because you’ll have communities that you’re serving deeply, who you’ve become valuable to, and who want to support you. That might be through donations or mutual aid or revenue or collaboration.

And we need the open social web to be sustainable. We need people to keep working on these problems. We need you to be able to work on this full-time without burning out.

These aren't just good questions to ask: they're survival questions. Because the threats communities are facing aren't abstract and we need the open social web to exist.

The threats are real

As I was writing this talk, an entire apartment building in Chicago was raided. Adults were separated into trucks based on race, regardless of their citizenship status. Children were zip tied to each other.

And we are at the foothills of this. Every week, it ratchets up. Every week, there’s something new. Every week, there’s a new restrictive social media policy or a news outlet disappears, removing our ability to accurately learn about what’s happening around us.

And, look, I don’t mean to scare or pressure you. I really don’t. But you have so much power.

The threats are real. But so is the community in this room. You have the skills, the values, and now hopefully a framework to build what's needed.

Everyone here has the potential to be building the future. You’re building platforms that provide an alternative to an authoritarian, extractive status quo, and every platform on the fediverse has the potential to help build a more informed and equal global society.

What I hope we'll all remember is that protocols and code are only valuable if they serve real communities with real needs. And today, there are communities facing real threats.

The opportunity right now isn't to build a better Twitter or to provide a nice place for people who care about Linux to chat: it's to build infrastructure that vulnerable people can actually use to organize, to communicate safely, and to build community. But we can only do that if we're building with those communities from day one, not building for them based on our assumptions about what they need.

Over the next two days, I hope you'll use those three questions as one of your lenses. Who is this really for? Are we the right people to build it? And does it concretely serve their real needs better than what exists today? Because the stakes are real, and there’s real scope to help.

Thank you

Thanks for listening.

If you want to yell at me, I understand. Here’s where to find me.

- Fediverse: @ben@werd.social

- Bluesky: @werd.io

- Web: werd.io

- Email: ben@werd.io