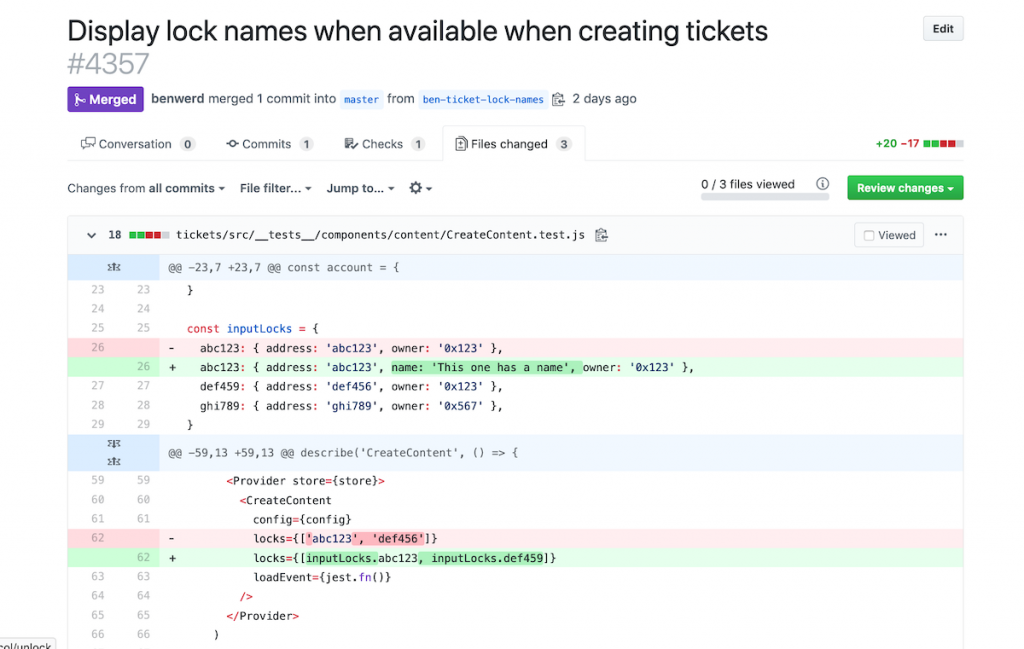

The modern software development process is aruably centered around something called a pull request. Here's a simplified version of how it works:

- All source code is stored in a source repository (there are many types, but git is the most popular).

- The main source code that everyone references is stored in a master branch.

- When a developer wants to make a change, they take a copy of the master branch and work on the copy.

- When they're finished, they submit their changes using a pull request. This

- Other developers on the project review the changes, and either request further changes, or accept the review (often with a simple "LG" or "LGTM": "Looks Good To Me").

- The changes can then be merged in to the master branch. The developer's changed copy is typically deleted; if they want to make more changes, they take a new copy.

This methodology ensures that every change has oversight, and while there's plenty of room for team dysfunction - reviewers wield a lot of power here - it typically makes for more stable code. On GitHub, the dominant platform for hosting code repositories, these kinds of code reviews can be set to be mandatory. It's rare to find an engineering team that doesn't use them.

At this point, it feels like pull requests are just part of the fabric of software development. But they were popularized by GitHub, and its version of the functionality has influenced how they work everywhere.

GitHub, in turn, was acquired by Microsoft for $7.5 billion last year. Microsoft's design decisions now influence how almost all software is made.

It would be easy - and lazy - to accept the pull request as it stands as the most optimal interaction for software development. After all, it seems to more or less work for code. But software is eating the world, and in a world where every aspect of society is influenced in some way by source code, we have a responsibility to examine the processes that are used to make it. We talk a lot, rightly, about the demographics of software teams and the power dynamics of funding, but it's also important to re-examine the core activities involved in building code itself.

The design of the platforms we use matters. The boxes we type into - whether on Twitter, Facebook, or elsewhere - influence the content we create.

Pull requests, in their current form, encourage teams to take a code-first approach without considering the human impact or social context of their work.

Every software project is built to help someone achieve some kind of goal. Understanding who that is, and how the software will be effective for them, is key to successful software: you can't just build something and hope it will be useful to someone. Maybe it will, and maybe it won't; you're leaving it up to luck. Adopting a human-centered development philosophy allows you to build an effective product (and if you're a startup, find product/market fit) far more quickly and cheaply than you could otherwise.

We also live in a world where the societal implications of the software we build are serious. One of the most eye-opening conversations in my working life was with Chelsea Manning. We were discussing a set of software projects I had been working to support, and I asked her what she thought. Some, she liked; but she pointed out that the technology involved in others could be used to harm. "[This project] could be used to target drones", she pointed out. I hadn't even considered it, and she was right.

A key question to building any software in the modern age is: "In the wrong hands, who could this harm?"

Decades ago, software seemed harmless. In 2019, when facial recognition is used to deport refugees and data provided by online services have been used to jail journalists, understanding who you're building for, and who your software could harm, are vital. These are ideas that need to be incorporated not just into the strategies of our companies and the design processes of our product managers, but the daily development processes of our engineers. These are questions that need to be asked over and over again.

It's no longer enough to build with rough consensus and running code. Empathy and humanity need to be first-class skills for every team - and the tools we use should reflect this.

Share this post

Share this post

I’m writing about the intersection of the internet, media, and society. Sign up to my newsletter to receive every post and a weekly digest of the most important stories from around the web.