If you take investment to build your product, you will one day need to find a way to repay those investors. That might be a risk that you need to take because you otherwise wouldn't be able to build the thing you want to. But it's a key part of the equation.

With no outside money, only people with copious spare time or disposable wealth can afford to build software of any complexity. I don’t see that as a desirable outcome, not just because it’s fundamentally unfair, but also because we then won’t get software built by people with a wider range of lived experiences, which means it will be less useful overall. We therefore need to have investors or grant-making institutions in the mix. Venture capital, though often maligned, has allowed a lot of services we all use to exist.

The trouble is, the need for exponential growth or revenue sometimes pit platforms against their users, which is death for a Web 2.0 business.

Web 2.0 businesses work by making their user-bases into part of the machine. They produce network effects, which means that the product becomes more valuable as more people use it. Reddit with one user is not particularly useful; Reddit with millions is a much more compelling place to converse.

For years, those user-bases have just sort of gone along with it. There have been minor skirmishes from time to time, but the utility of the platform itself has generally been enough to keep people engaging.

Twitter’s implosion changed that. Millions of people decamped from the platform to places like Mastodon — and some of them to nowhere at all. More than creating a problem for Twitter and an opportunity for anyone working on alternatives, this mass movement of users also opened the floodgates for more direct action among Web 2.0 users.

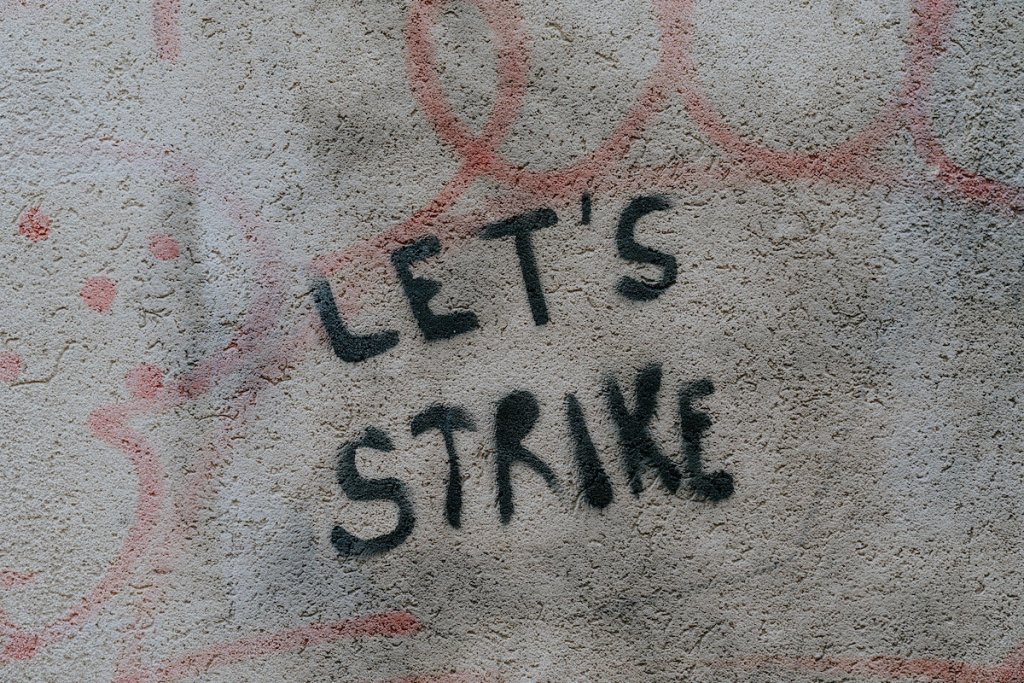

Over 87% of subreddits - the themed discussion communities that make up Reddit - went on strike this week in protest of new API policies that price most apps out of the market. When CEO Steve Huffman issued a tone-deaf internal memo suggesting that this, too, would pass, they decided to extend the action. In effect, the vast majority of the site has been shut down. Huffman lost the respect of the people who had, up to then, been willingly part of his machine.

In the old days, we talked about Web 2.0 “democratizing” industries. Blogging democratized publishing. Flickr democratized photo discovery and use. Delicious democratized … bookmarks, I guess? Because these use cases represented a move away from centralized publishing models where an elite few controlled who could be seen and heard, they were democratized, in a sense. But the platforms themselves continued to be built, run, and funded by an elite few. There was no democratization of power or equity. As has long been the case with mass media, the users were not the customers; they were the product being sold.

While there were always people who discussed these obvious harms and advocated for solutions — long-time members of the indieweb community and its cousins, for example — these were not mainstream topics. The cracks really began to show after the 2016 election, when Facebook finally caught some criticism for its flippancy towards democracy. Subsequently, stories about its role in genocide, its misrepresentation of its own engagement analytics to news organizations, and other harms became more widespread.

But while there has always been some sporadic direct action — there have been a few third-party tools that have let people delete their content and connections from Facebook, for example; LiveJournal users finally left en masse after its sale to a Russian media company which enacted homophobic and anti-politics policies — we haven’t seen anything on the level of this year’s. Millions of Twitter users quit following Elon Musk’s acquisition, and now most of Reddit is offline.

Reddit is the perfect testbed for this kind of collective user action. Each individual subreddit is controlled by a set of moderators who have the power to turn their communities off — which is exactly what they’ve done. But Reddit isn’t the only platform with this dynamic: a 2021 report by the NYU Governance Lab suggested that 1.8 billion people use Facebook Groups every month. Admins of those groups have remarkable power over the Facebook platform.

This has the potential to be a radical change. Once users realized that they have power as a community, the fundamental dynamics of these platforms changes. You can no longer engage in adversarial business practices: there’s nothing wrong with making money, but it will need to be in a way that aligns with the people who give a platform its value.

Not only should that give the leadership of more established Web 2.0 businesses pause, it should inform early decisions by both investors and founders of any new collaborative platform on the internet. An adversarial business model, or a hand-wavey one like “selling data”, has the potential to deeply harm the value of a venture that depends on its users further down the road.

The health, trust, and safety of a platform’s community is paramount. The potential for collective action means that, finally, users can have some say in how the platforms they use are run. We may even see more platforms move to co-operative and community-owned models as a way to ensure that they remain aligned with their ecosystems: it’s not just good ethics, but it’s good business sense in a world where users, admins, and third-party app developers understand that they have the power to leave.

We may even see moderator’s unions, providing collective bargaining, advice, and other benefits for people who run communities across platforms. Perhaps even bonuses like negotiated healthcare that industrial unions have long provided. There’s honestly no reason why not: these people are the direct drivers of millions upon millions of dollars for platform owners. They have power; they just have to stand up and use it.

Share this post

Share this post

I’m writing about the intersection of the internet, media, and society. Sign up to my newsletter to receive every post and a weekly digest of the most important stories from around the web.