This is my monthly roundup of the links, books, and media I found interesting. Do you have suggestions? Let me know!

Apps + Websites

AI

Generative AI: What You Need To Know. “A free resource that will help you develop an AI-bullshit detector.”

Games

TimeGuessr. Fun little game that asks you to guess the place and time a series of photos were taken. My best score so far: 38,000.

Moderator Mayhem: A Content Moderation Game. This is HARD. Which is the point.

Technology

See your identity pieced together from stolen data. “Have you ever wondered how much of your personal information is available online? Here’s your chance to find out.” Really well-executed.

Books

Fiction

Severance, by Ling Ma. Though it fades out weakly, I loved this story about loss, meaning, and what it means to be an immigrant, dressed up as a science fiction novel. The science fiction is good too, and alarmingly close to the real-life global pandemic that took place a few years after it was written. This is a book about disconnection; it resonated for me hard.

Streaming

Documentary

Little Richard: I Am Everything. A well-argued documentary that does an excellent job of showing the debt every rock musician has to Little Richard - and, in turn, how rock and roll was birthed as a Black, queer medium. Joyous and revelatory.

Notable Articles

AI

‘This robot causes harm’: National Eating Disorders Association’s new chatbot advises people with disordering eating to lose weight. ““Every single thing Tessa suggested were things that led to the development of my eating disorder,” Maxwell wrote in her Instagram post. “This robot causes harm.””

Google Unveils Plan to Demolish the Journalism Industry Using AI. “If Google’s AI is going to mulch up original work and provide a distilled version of it to users at scale, without ever connecting them to the original work, how will publishers continue to monetize their work?”

Indirect Prompt Injection via YouTube Transcripts. “ChatGPT (via Plugins) can access YouTube transcripts. Which is pretty neat. However, as expected (and predicted by many researches) all these quickly built tools and integrations introduce Indirect Prompt Injection vulnerabilities.” Neat demo!

ChatGPT is not ‘artificial intelligence.’ It’s theft. “Rather than pointing to some future utopia (or robots vs. humans dystopia), what we face in dealing with programs like ChatGPT is the further relentless corrosiveness of late-stage capitalism, in which authorship is of no value. All that matters is content.”

Google Bard is a glorious reinvention of black-hat SEO spam and keyword-stuffing. “Moreover, researchers have also discovered that it’s probably mathematically impossible to secure the training data for a large language model like GPT-4 or PaLM 2. This was outlined in a research paper that Google themselves tried to censor, an act that eventually led the Google-employed author, El Mahdi El Mhamdi, to leave the company. The paper has now been updated to say what the authors wanted it to say all along, and it’s a doozy.”

OpenAI's ChatGPT Powered by Human Contractors Paid $15 Per Hour. “OpenAI, the startup behind ChatGPT, has been paying droves of U.S. contractors to assist it with the necessary task of data labelling—the process of training ChatGPT’s software to better respond to user requests. The compensation for this pivotal task? A scintillating $15 per hour.”

Schools Spend Millions on Evolv's Flawed AI Gun Detection. “As school shootings proliferate across the country — there were 46 school shootings in 2022, more than in any year since at least 1999 — educators are increasingly turning to dodgy vendors who market misleading and ineffective technology.”

Will A.I. Become the New McKinsey? “The doomsday scenario is not a manufacturing A.I. transforming the entire planet into paper clips, as one famous thought experiment has imagined. It’s A.I.-supercharged corporations destroying the environment and the working class in their pursuit of shareholder value.”

Google "We Have No Moat, And Neither Does OpenAI". “Open-source models are faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable. They are doing things with $100 and 13B params that we struggle with at $10M and 540B. And they are doing so in weeks, not months. This has profound implications for us.”

Economists Warn That AI Like ChatGPT Will Increase Inequality. “Most empirical studies find that AI technology will not reduce overall employment. However, it is likely to reduce the relative amount of income going to low-skilled labour, which will increase inequality across society. Moreover, AI-induced productivity growth would cause employment redistribution and trade restructuring, which would tend to further increase inequality both within countries and between them.”

Climate

Earth is in ‘the danger zone’ and getting worse for ecosystems and humans. “Earth has pushed past seven out of eight scientifically established safety limits and into “the danger zone,” not just for an overheating planet that’s losing its natural areas, but for well-being of people living on it, according to a new study.”

Outrage as Brazil law threatening Indigenous lands advances in congress. “Lawmakers had sent “a clear message to the country and the world: Bolsonaro is gone but the extermination [of Indigenous communities and the environment] continues,” the Climate Observatory added.”

Documents reveal how fossil fuel industry created, pushed anti-ESG campaign. “ESG’s path to its current culture war status began with an attempt by West Virginia coal companies to push back against the financial industry’s rising unease around investing in coal — which as the dirtiest-burning fuel has the most powerful and disrupting impacts on the climate.”

Petition: Global Call for the Urgent Prevention of Genocide of the Indigenous Peoples in Brazil. “As citizens from all over the world, we are uniting our voices to demand urgent justice for the indigenous peoples of Brazil.” This is urgent; please sign.

Recycled plastic can be more toxic and is no fix for pollution, Greenpeace warns. “But … the toxicity of plastic actually increases with recycling. Plastics have no place in a circular economy and it’s clear that the only real solution to ending plastic pollution is to massively reduce plastic production.”

CEO of biggest carbon credit certifier to resign after claims offsets worthless. “It comes amid concerns that Verra, a Washington-based nonprofit, approved tens of millions of worthless offsets that are used by major companies for climate and biodiversity commitments.”

New York is sinking, and its bankers could go down with it. “When discussing climate change that banker suggested that sinking cities was the biggest problem he thought the sector faced. Over 80% of the property portfolio of many banks was, he suggested, in cities where the likelihood of flooding was likely to increase rapidly.”

New York City is sinking due to weight of its skyscrapers, new research finds. “The Big Apple may be the city that never sleeps but it is a city that certainly sinks, subsiding by approximately 1-2mm each year on average, with some areas of New York City plunging at double this rate, according to researchers.”

Crypto

Narrative over numbers: Andreessen Horowitz's State of Crypto report. “The result of this approach is an incredibly shameless piece of propaganda showing the extents to which Andreessen Horowitz is willing to manipulate facts and outright lie, hoping to turn the sentiment on the crypto industry back to where retail investors were providing substantial pools of liquidity with which they could line their pockets. If anyone still believes that venture capital firms like Andreessen Horowitz are powerful sources of innovation and societal benefit, I hope this will give them pause.”

Culture

Jesse Armstrong on the roots of Succession: ‘Would it have landed the same way without the mad bum-rush of Trump’s presidency?’. “I guess the simple things at the heart of Succession ended up being Brexit and Trump. The way the UK press had primed the EU debate for decades. The way the US media’s conservative outriders prepared the way for Trump, hovered at the brink of support and then dived in.”

Creative Commons Supports Trans Rights. “As an international nonprofit organization, with a diverse global community that believes in democratic values and free culture, the protection and affirmation of all human rights — including trans rights — are central to our core value of global inclusivity and our mission of promoting openness and providing access to knowledge and culture.” Right on. Trans rights are human rights.

The Real Difference Between European and American Butter. “Simply put, American regulations for butter production are quite different from those of Europe. The USDA defines butter as having at least 80% fat, while the EU defines butter as having between 82 and 90% butterfat and a maximum of 16% water. The higher butterfat percentage in European butter is one of the main reasons why many consider butters from across the pond to be superior to those produced in the US. It’s better for baking, but it also creates a richer flavor and texture even if all you’re doing is smearing your butter on bread. On the other hand, butter with a higher fat percentage is more expensive to make, and more expensive for the consumer.”

Democracy

How I Won $5 Million From the MyPillow Guy and Saved Democracy. “But if more people sought truth, even when that truth is contrary to their beliefs — such as when a Republican like me destroys a Republican myth — then I think we really can save democracy in America. In fact, I think that’s the only way.”

Henry Kissinger at 100: Still a War Criminal. “Kissinger’s diplomatic conniving led to or enabled slaughters around the globe. As he blows out all those candles, let’s call the roll.”

Georgia GOP Chair: If the Earth Really Is Round, Why Are There So Many Globes Everywhere?“Everywhere there’s globes…and that’s what they do to brainwash… For me, if it is not a conspiracy, if it is, you know, ‘real,’ why are you pushing so hard? Everywhere I go, every store, you buy a globe, there’s globes everywhere—every movie, every TV show, news media, why?”

NAACP warns Black Americans against traveling to Florida because of DeSantis policies. “On Saturday, the NAACP joined the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), a Latino rights advocacy group, and Equality Florida, an LGBTQ rights advocacy group, in issuing Florida travel advisories.”

May Anti-Trans Legislative Risk Map. “The map of anti-trans risk has polarized into two Americas - one where trans people have full legal protections, and one where they are persecuted by the state.”

Techbro SF. “San Francisco is a dystopian hellhole caught in doomloop and it is all because everyone hates techbros. Well, we are tired of being disrespected. Therefore we are going to attack those who can’t fight back, yes, poor people.”

One year after Dobbs leak: Looking back at the summer that changed abortion. “The 19th spoke with people from across the country about those historic days: lawmakers, physicians, organizers on both sides of the abortion fight and pregnant people navigating a new world.” What a newsroom.

Health

Can Americans really make a free choice about dying? A characteristically nuanced, in-depth piece about the debate around assisted suicide.

One more dead in horrific eye drop outbreak that now spans 18 states. An actual nightmare.

Widely used chemical strongly linked to Parkinson’s disease. “A groundbreaking epidemiological study has produced the most compelling evidence yet that exposure to the chemical solvent trichloroethylene (TCE)—common in soil and groundwater—increases the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.” By as much as 70%!

Labor

Of Course We Should All be Working Less. “In 1940, the Fair Labor Standards Act reduced the workweek to 40 hours. Today, as a result of huge advances in technology and productivity, now is the time to lower the workweek to 32 hours—with no loss in pay. Workers must benefit from advanced technology, not just the 1%.”

Hollywood writers strike could impact diverse stories on TV and in film. “When Kyra Jones wrote for the ABC broadcast show “Queens,” she collected a $14,000 residuals check that helped her get through the months after the project ended and she was without work. Then last summer, she got her first residuals check for writing on the Hulu streaming show “Woke.” It was $4.”

Business Mentality. “Hi, we’re the company you work for and we care about your mental health!”

Hustle culture is over-rated. “When hustle culture is glorified, it incentivizes people to work longer hours, not because it’s a good way to get the work done, but because they want to be perceived as working long hours.”

Media

How We Reached Dairy Farm Workers to Write About Them. “The reporters’ process underscores one of our central beliefs at ProPublica: Publishing a story about injustice isn’t enough if we don’t reach the people who are directly affected.”

2023: The year equitable journalism goes mainstream. “For too long, journalism has had a laser focus on holding power to account, rather than widening its aperture to recognize the opportunity to build and share power in and with communities.”

Unconstitutional TikTok ban would open the door to press censorship. “But if we accept the arguments for banning TikTok, what might come next? The consequences are even more catastrophic. Bans on foreign news websites that track Americans’ clicks and comments? For example, the Guardian must have a gold mine of information on the millions of Americans that read it every day.”

It’s Time to Acknowledge Big Tech Was Always at Odds with Journalism. “Do we want to preserve the dominance of companies that like to act as if they are neutral communications platforms, when they also act as publishers without the responsibilities that come with that? Do we want digital behemoths to accumulate so much power that they can exploit personal data in ways that buttress their dominance and diminish the value of news media audiences?”

How we told the story of the summer Roe v. Wade fell. “We knew this wouldn’t be an easy feat to pull off. But this project, while technically reported over the past five months, benefited from years of our work covering abortion at The 19th. After working nonstop since 2021 to cover the looming fall of Roe, I had built a list of sources whose stories I knew would be instructive and illuminating. And I knew that they would trust me to do a thorough, accurate job.”

Grist and the Center for Rural Strategies launch clearinghouse for rural US coverage. “The Rural Newswire was created to help newsrooms that serve rural communities by providing a platform to both find and share stories that can be republished for free. Editors can use the Rural Newswire to source stories to syndicate, and they can also upload links to their own coverage. As part of this project, together the Center for Rural Strategies and Grist are providing $100,000 in grants to report on rural America. The grants are open to both newsrooms and freelancers.”

Elon Musk thinks he’s got a “major win-win” for news publishers with…micropayments. “In a digital universe where every news story is behind a hard paywall — one impenetrable to the non-paying reader — then a micropayments model might make sense. But that’s not the digital universe we live in.”

Society

Seniors are flooding homeless shelters that can’t care for them. “Nearly a quarter of a million people 55 or older are estimated by the government to have been homeless in the United States during at least part of 2019, the most recent reliable federal count available.” Hopelessly broken.

Letter from Jourdon Anderson: A Freedman Writes His Former Master. “Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.”

A College President Defends Seeking Money From Jeffrey Epstein. ““People don’t understand what this job is,” he said, adding, “You cannot pick and choose, because among the very rich is a higher percentage of unpleasant and not very attractive people. Capitalism is a rough system.””

Startups

My New Startup Checklist. Interesting to see what creating a new startup entails in 2023.

What a startup does to you. Or: A celebration of new life. “Just like having kids, you won’t understand until you do it. But if you do it, even if you “fail,” you will come out stronger than you could have ever been without it. Stronger, wiser, ready for the next thing, never able to go back to being a cog, eyes opened.”

Technology

Block Party anti-harassment service leaves Twitter amid API changes. “Announced in a blog post last night, Block Party’s anti-harassment tools for Twitter are being placed on an immediate, indefinite hiatus, with the developers claiming that changes to Twitter’s API pricing (which starts from $100 per month) have “made it impossible for Block Party’s Twitter product to continue in its current form.””

How Picnic, an Emerging Social Network, Found its Niche. “By putting a degree of financial incentive in the hands of moderators by offering them fractional ownership of the community they built through a system of “seeds,” they ultimately are able to control their community’s destiny.”

Twitter Fails to Remove Hate Speech by Blue-Check Users, Center for Countering Digital Hate Says.“Twitter is failing to remove 99 percent of hate speech posted by Twitter Blue users, new research has found, and instead may be boosting paid accounts that spew racism and homophobia.” Who would have predicted?

Power of One. “It’s not about how many views you have, how many likes, trying to max all your stats… sometimes a single connection to another human is all that matters.”

Social Media Poses ‘Profound Risk’ to Teen Mental Health, Surgeon General Warns. “Frequent social media use may be associated with distinct changes in the developing brain in the amygdala (important for emotional learning and behavior) and the prefrontal cortex (important for impulse control, emotional regulation, and moderating social behavior), and could increase sensitivity to social rewards and punishments.”

Leaked EU Document Shows Spain Wants to Ban End-to-End Encryption. “Breaking end-to-end encryption for everyone would not only be disproportionate, it would be ineffective of achieving the goal to protect children.” It would also put a great many more people at risk.

Growing the Open Social Web. “I think there are two big things that would help the Open Social Web seize this opportunity to reach scale.” A big yes to all of this.

Hype: The Enemy of Early Stage Returns. “Technology alone does not create the future. Instead, the future is the result of an unpredictable mix of technology, business, product design, and culture.”

Montana becomes first US state to ban TikTok. “Montana has became the first US state to ban TikTok after the governor signed legislation prohibiting mobile application stores from offering the app within the state by next year.” I’m willing to wager that this never comes to pass.

Many US Twitter users have taken a break from Twitter, and some may not use it a year from now. “A majority of Americans who have used Twitter in the past year report taking a break from the platform during that time, and a quarter say they are not likely to use it a year from now.”

Why elite dev teams focus on pull-request metrics. “What’s clear from this study is elite development workflows start and end with small pull request (PR) sizes. This is the best indicator of simpler merges, enhanced CI/CD, and faster cycle times. In short, PR size affects all other metrics.”

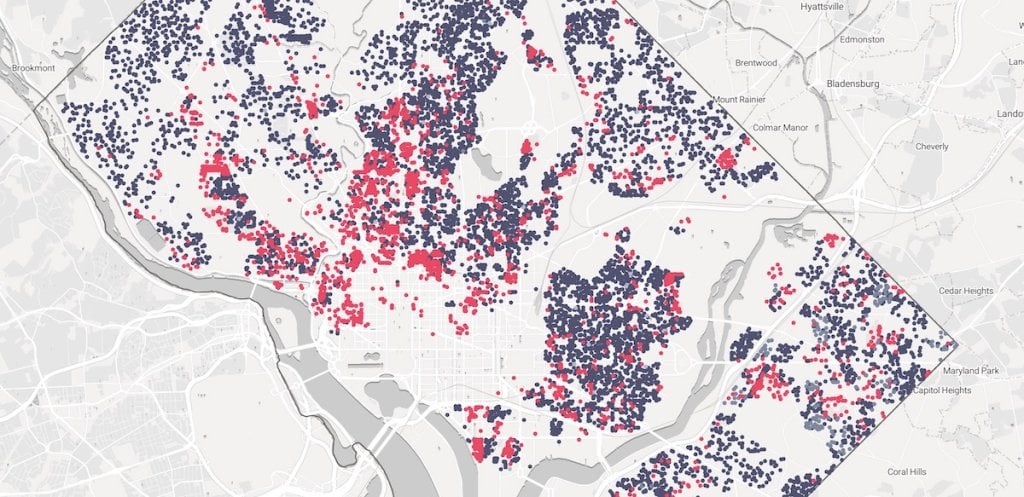

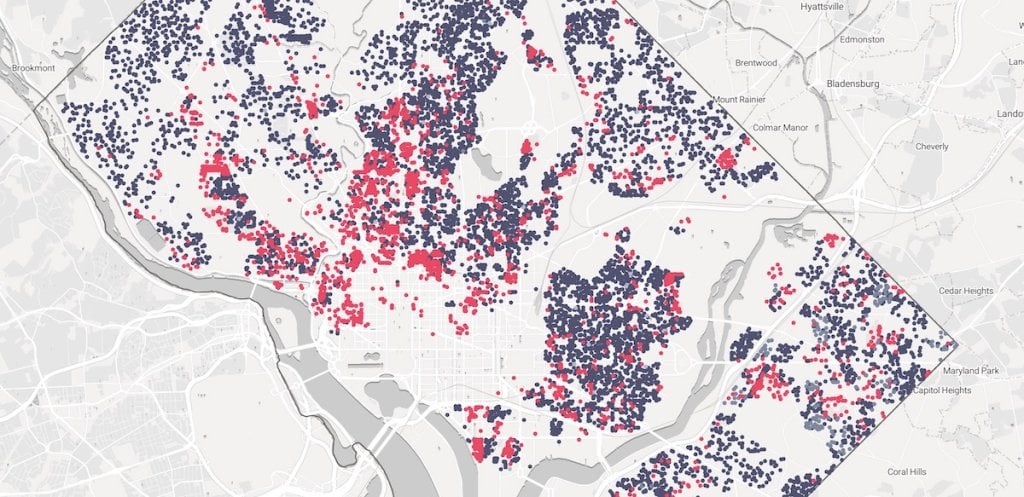

See the Neighborhoods Internet Providers Excluded from Fast Internet. “A Markup analysis revealed that the worst internet deals disproportionately fell upon the poorest, most racial and ethnically diverse, and historically redlined neighborhoods in all but two of the 38 cities in our investigation.”

How people are archiving the storytelling and community behind Black Twitter. “They see an urgency to preserving Black Twitter in a world in which Black history and Black women’s cultural labor are undervalued or unacknowledged — and where the future of Twitter seems unknown. They also want to document the racist and sexist abuse that Black women on the platform received, in part to help people dream up and create a more inclusive way of connecting that prioritizes the needs of the most marginalized.”

Google AMP: how Google tried to fix the web by taking it over. “In 2015, Google hatched a plan to save the mobile web by effectively taking it over. And for a while, the media industry had practically no choice but to play along.”

The UX Research Reckoning is Here. “It’s not just the economic crisis. The UX Research discipline of the last 15 years is dying. The reckoning is here. The discipline can still survive and thrive, but we’d better adapt, and quick.”

The web's most important decision. “But also, and this is important to mention, they believed in the web and in Berners-Lee. The folks making these decisions understood its potential and wanted the web to flourish. This wasn’t a decision driven by profit. It was a generous and enthusiastic vote of confidence in the global ambitions of the web.”

Blue skies over Mastodon. “One of big things I’ve come to believe in my couple of decades working on internet stuff is that great product design is always holistic: Always working in relation to a whole system of interconnected parts, never concerned only with atomic decisions. And this perspective just straight-up cannot emerge from a piecemeal, GitHub-issues approach to fixing problems. This is the main reason it’s vanishingly rare to see good product design in open source.”

Share this post

Share this post