I previously co-founded Elgg and served as CTO at latakoo, but Known is the first time I've been a CEO. Candid reflections have always been important to me to learn from; maybe someone will find these useful, too. If not, then, well, my first point applies:

Writing is an important way to organize your thoughts.

In many ways, as a founder, your job is to be the company storyteller, the company cheerleader, and the person who will fix the sink if the plumbing breaks. There are so many strands that I've found writing - and in particular, blogging - to be a great way to order them into a coherent narrative. A lot of times, when I post here on my own site, I'm thinking things out in public. You're all a part of my thought process. Congratulations?

This is one reason why I'm adamant that you should hire people who can write well. I don't mean their spelling or punctuation, particularly; I'm talking about their ability to convey information. That also speaks to the kind of order they will bring to other tasks. It's a core skill.

Related to this:

The elevator pitch is more important than I thought it would be.

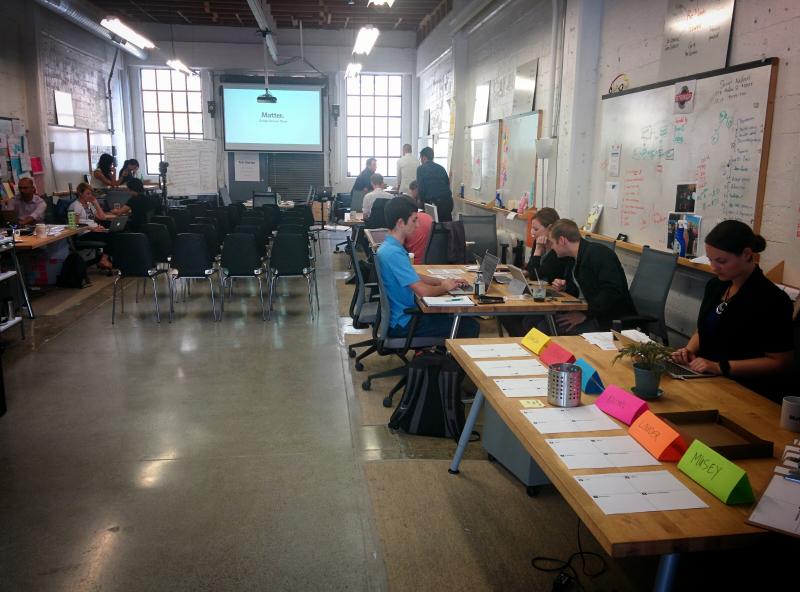

We were part of the third class at Matter, an awesome values-based accelerator in downtown San Francisco. Throughout, we were encouraged to condense our story into a seven-minute pitch. The pitch itself wasn't the thing; the process forced us to create a coherent story for our company, mostly for ourselves, which would itself inform our company's decisions. Who would buy this? What was the concrete problem we were trying to solve?

It's harder than you think to condense this into seven minutes. We live and breathe our startups - how can we cut and edit that down to a seven minute story? Help! we all thought to ourselves, while nibbling slack-jawed at our accelerator's complementary snacks. We need more time!

If only we'd known.

Seven minutes is an acre of time. It's a boundless ocean stretching out to the horizon, rippling gently beneath a benevolent sun. You can fit lifetimes in seven minutes. And in front of a captive demo day audience, to boot!

No no, my optimistic, accelerator-cheese-string-eating past self. You have got it very wrong. Try fifteen seconds.

"What is Known?", someone will ask. Ignore the existential double meaning of the question, because you have about fifteen seconds to convince the person in front of you that your idea is compelling and different. If you succeed, they might ask you a follow-up question: something easy like "are you making money?" or "doesn't WordPress do that?". Be ready.

In fact, the existential double meaning does matter, because your answer, despite being tweet-sized, will depend on all the research and insights you've gathered, and everything you know. It's likely to radically change over time as your understanding of your business improves. Your fifteen second description is the tip of the iceberg, but it's a tip that encapsulates everything below the waterline.

Arguing with investors is a clear indicator that you have work to do. On yourself.

This is something I've avoided, but I've seen other founders do this more times than I can count.

Here's what happens. A startup founder takes a meeting or walks on-stage at a pitch event. They've brought a presentation that they've slaved over, had sleepless nights over, maybe even wept over in the darkness of their shared office space at 3am, and they are proud of it. It is, as far as they can tell through their sleepless haze, the perfect encapsulation of what they've worked on so tirelessly. It is beautiful. Were it journalism, it would surely win the Pulitzer.

And the investors tear it apart.

At least, to the entrepreneur, it feels like that. In reality, they're asking important due diligence questions: trying to pick holes in the story, and figuring out, within the constraints of the space and time they have, whether this startup is a smart place to put their money. They most often want to help the entrepreneur, by asking them to strengthen their argument. But it flies directly in the face of the founder's conviction, not to mention all of their single-minded hard work, and it hurts. So they misread the situation and become defensive. They might even get visibly angry. And that's where it all falls down.

An early-stage investor is like a cofounder (or at least, they should be). They probably have a lot more experience with young companies than the founder does, and can offer pertinent advice based on things they've learned from other companies. Who would want to work with someone who gets angry when presented with that experience?

It's okay to correct people, of course, but the right way to do it is with your facts, and all the great research you've done. Your faith means nada: all startup founders have faith that they'll succeed. You've got to show investors that you have the skills, the knowledge and - ideally - an unfair advantage.

Take care of yourself.

Here's what I have experienced personally: the crushing feeling of having your work swept out from under you by that investor experience. There's a tight line to walk. Investors really do have a lot of experience, and really do want to help you. Most of the people I've met are driven by helping entrepreneurs, so the advice they give comes from a good place. But at the same time, you have to stay true to yourself, too: sometimes you do need to take a leap of faith to create something new. Whether anyone comes with you is all on you.

That's hard. Running a startup comes with intense highs and lows, sometimes within the same 30 minute period. Often that 30 minute period will be late at night, or on a Sunday, or at 6am. By its nature, it's incredibly unhealthy, both mentally and physically.

When you're terrified about money, and worried about your own lack of sleep, and there's a strange new pain somewhere in your body and you're not sure when it started happening but it's probably stress-related but maybe it's something that will kill you, and people have started looking at you strangely on the street, it can be very hard to make stable, considered decisions. But that's what you have to do. You have to be calm, and you can't let criticism go to your heart.

Take time away from your startup. Go to the gym. Eat well (not string cheese). Consider drinking tea instead of coffee (you don't need higher cortisol levels). Enjoy the countryside. Go for walks. Be with your friends. Do what makes you happy. Above all: remember that it's a business, not your entire life, and any criticism or praise you receive is not a commentary on you as a person.

Those things will make you a better person, a better entrepreneur, and a better decision-maker.

And for god's sake, stop eating the string cheese.

Don't tilt at windmills.

Fail hella fast. Don't spend years on something that isn't going to succeed for you. You only get one life. If something isn't working after you've spent a reasonable amount of time and effort on it, move onto something that does. Don't get so emotionally invested that you can't let go. (This applies not just to startups as a whole, but to features, target customers, user flows, logos ... you name it. Repeat after me: this is business.)

A mantra that's commonly (rightly) repeated for startup founders is, "you are not Steve Jobs". In other words, you need to do user research and testing. You need to build prototypes to get feedback on, so you can make better decisions.

But, okay, time out. Here's a quick question which should be easy to answer with no thought at all: what is success?

Does success mean building a unicorn or a dragon? (That's startup-speak for a company worth at least $1bn, and a company that returns $1bn to a particular investor, respectively. Yes, I know it's ridiculous. Have you been here?)

Does success mean building the dreaded lifestyle business? (That's startup-speak for a company that allows its founders to live comfortably but will never be described in terms of mythical beasts.)

Does success mean making a positive impact on the world? (That's startup-speak for "won't get funded". I kid - these kinds of startups can also make a lot of money, and Matter, as well as Better Ventures, Double Bottom Line and a few other social impact investment firms are orientated to this. I'm glad they exist.)

It's actually really important that you know the answer to this. All of these approaches lead to different approaches and decisions, different ways of describing your company, and, frankly, different companies. If you have a cofounder (and you should), you should probably be on the same page on this. If one of you wants to build a unicorn filled with ninjas that morphs into a dragon, and one of you wants to build a lifestyle business with a focus on social impact, you will reach a point where it's not going to be pretty. Founder breakups are like marriage breakups. You don't want it to happen.

Above all else: know where the money is coming from.

A lot of people have been seduced by Twitter's strategy. Here's the in-a-nutshell version of what they did: they built a prototype in a couple of weeks, with the simplest possible features, and let it loose. Over time, the community created its own norms - things like replies, hashtags and retweets - and the company thought about those and figured out how to make them into features. For a few years they didn't even think about money. They concentrated on growing the company, and to do that they paved the deer paths. Lovely!

What's mentioned less often is that to make this happen, Ev Williams personally bought back the shares that had been invested in his company. That money had previously come from selling Blogger to Google. Unless you also have millions and millions of dollars, it is not a strategy that you can repeat. And even then, Twitter partially became successful through a series of smart decisions - putting screens up at SXSW, for example, which took money - and a series of accidents.

To "you are not Steve Jobs", I would like to add: "you are not Ev Williams".

The startup landscape has changed since the mid-2000s. It is expected that you will have built something with traction off your own back. Unless you're a unicorn developer (which in this case doesn't mean you're worth $1bn, but means you can build quickly, can design well and are good at gathering user feedback; stay with me) you will need to bring in other people. That means you're going to need to commit your own money, or be oozing with leadership charisma, or both.

Here's an aside, if you aren't a developer: you can't find a technical cofounder. Technical people get asked to join startups on a very regular basis, and it's become a bit of a running joke. Join a company that will eat your life and pay you very little money in exchange for a tiny amount of equity that amounts to a lottery ticket? "What a great deal!" said no-one, ever. If you want someone technical to join your team as a cofounder, you have to prove that you're worth joining. Most of all, you have to prove that you're not going to lean on them to make your whole product for you - and that means showing that you have skills to bring to the table. Show your research. Build wireframes. Maybe even learn to code a little. And demonstrate, however you can, that your technical cofounder will be an equal rather than - as I heard someone once describe their technical colleagues - "our back-room technicians".

Once you have your working prototype - which, to reiterate, you've built with your own skills and/or money - you're going to need to know where your runway is coming from. Are you going to try and make revenue immediately? Are you going to raise investment because you're creating a consumer startup? Either way, you don't have space to bimble along like Twitter did, finding itself along the way.

Are you going to grow with help from investment? Then make sure people will invest. Are you going to bootstrap through revenue? Then make sure people will actually pay.

There is never enough time. There is never enough money. Somehow, as a founder, you have to make both.

Bonus seventh: don't trust pithy thought pieces on entrepreneurship.

Experience is important to learn from, but seriously. You're your own person. You have your own experience, your own goals, your own creativity and your own special sauce that you're going to bring to the table. There are few communities that are as much about peer pressure, community norms and cargo cultish received wisdom than tech entrepreneurship. Through all of this, you need to maintain your own strong personalty - and the strong personality of your venture.

Let me be clear: this is the best job I've ever had, and I wouldn't change it for anything.

Go out into the world and succeed, whatever that means for you, however it makes sense for you. Make a dent in the universe.

And don't eat the string cheese.

Share this post

Share this post Here's how it works: each company (including ours) receives a $50,000 investment to ensure your team is undistracted over the summer. After a bootcamp in the first week, you spend a little over four months researching, prototyping and refining. For two days each week, you have the opportunity to meet with outside mentors; once a week, each startup shares something with the class. At the end of each month, there's a design review, wherein you spend seven minutes pitching your company to a panel of investors and entrepreneurs. It's a confidential, safe environment, but the feedback is real, and panelists and audience members are encouraged to give "gloves off" advice. Based on that, you sprint to the next design review, and ultimately, to demo days in San Francisco and New York.

Here's how it works: each company (including ours) receives a $50,000 investment to ensure your team is undistracted over the summer. After a bootcamp in the first week, you spend a little over four months researching, prototyping and refining. For two days each week, you have the opportunity to meet with outside mentors; once a week, each startup shares something with the class. At the end of each month, there's a design review, wherein you spend seven minutes pitching your company to a panel of investors and entrepreneurs. It's a confidential, safe environment, but the feedback is real, and panelists and audience members are encouraged to give "gloves off" advice. Based on that, you sprint to the next design review, and ultimately, to demo days in San Francisco and New York. There's a widely-accepted maxim in software, and particularly in open source: scratch your own itch. That's certainly the mindset I walked in the door with. Although that can be helpful in the sense that it may reveal insights, user research is important if you want to reach people who aren't exactly like you. It was a hard transition, at least at first; here, the technology itself has little value unless it's meeting a deep, and scalable, user need. Halfway through the program, I was doing some pretty existential self-questioning. But ultimately, it was rewarding. As I write this, on my way to the New York demo day, thousands of people have used Known. Our initial focus, developed through extensive research, is on university educators, which has turned out to be a perfect decision: our first pilots are running right now, and we have more scheduled in the fall.

There's a widely-accepted maxim in software, and particularly in open source: scratch your own itch. That's certainly the mindset I walked in the door with. Although that can be helpful in the sense that it may reveal insights, user research is important if you want to reach people who aren't exactly like you. It was a hard transition, at least at first; here, the technology itself has little value unless it's meeting a deep, and scalable, user need. Halfway through the program, I was doing some pretty existential self-questioning. But ultimately, it was rewarding. As I write this, on my way to the New York demo day, thousands of people have used Known. Our initial focus, developed through extensive research, is on university educators, which has turned out to be a perfect decision: our first pilots are running right now, and we have more scheduled in the fall.

Friday marked the end of my first full-time week at

Friday marked the end of my first full-time week at