I’ve realized that I need to temper my enthusiasm for Mastodon. I worked on open source social networking platforms for a full decade of my life, and I’m very emotionally attached to this moment. I really want the fediverse to work.

I come by it honestly: I do think that a collectively-owned platform based on open protocols and an ecosystem of compatible tools - a social commons - is both more ethical and more resilient than a platform that is owned and run by a giant corporation with thousands of employees, shareholder obligations, and valuation requirements.

But my emotional involvement has led to me finding myself wanting to be reflexively defensive about its shortcomings, and this serves nobody. I’m enthusiastic about it, but many of the problems that people are bringing up are legitimate worries - and some of them may be showstoppers if they aren’t dealt with quickly.

I’m particularly concerned with moderation. In the fediverse, every server has a different set of content policies and a different team of moderators. Theoretically, this is good: people with specific needs or from vulnerable communities can find themselves posting from a more supportive context than they might find on monolithic social media. Field-specific instances, for example in genetics, can establish content policies relating to scientific accuracy that couldn’t possibly be enforceable on a monolithic site. But at the same time, this patchwork of content policies mean that moderation can be arbitrary and hard to understand.

Journalist Erica Ifill woke up this morning to find that she’d been banned from her Mastodon instance for no obvious reason. Block Party founder Tracy Chou’s content was removed from the largest instance on the grounds that criticizing patriarchy was sexism. In both cases, the action was reversed with an apology, but harm was done. An understanding of power imbalances is an important part of being a content moderator, but while software is provided to technically moderate, there are very few ecosystem resources to explain how to approach this from a human perspective. Open source software can sometimes fall into the trap of confusing code for policy, and Mastodon is no exception.

And then there’s the harassment. As caroline sinders wrote:

The blocking feature is like horror house anxiety game- I block when I see their new account, hoping I’ve now blocked all of them but knowing I probably never will. Because it’s a federated system, and you can have accounts on multiple servers, it means there’s multiple accounts I have to block to create some digital safety and distance.

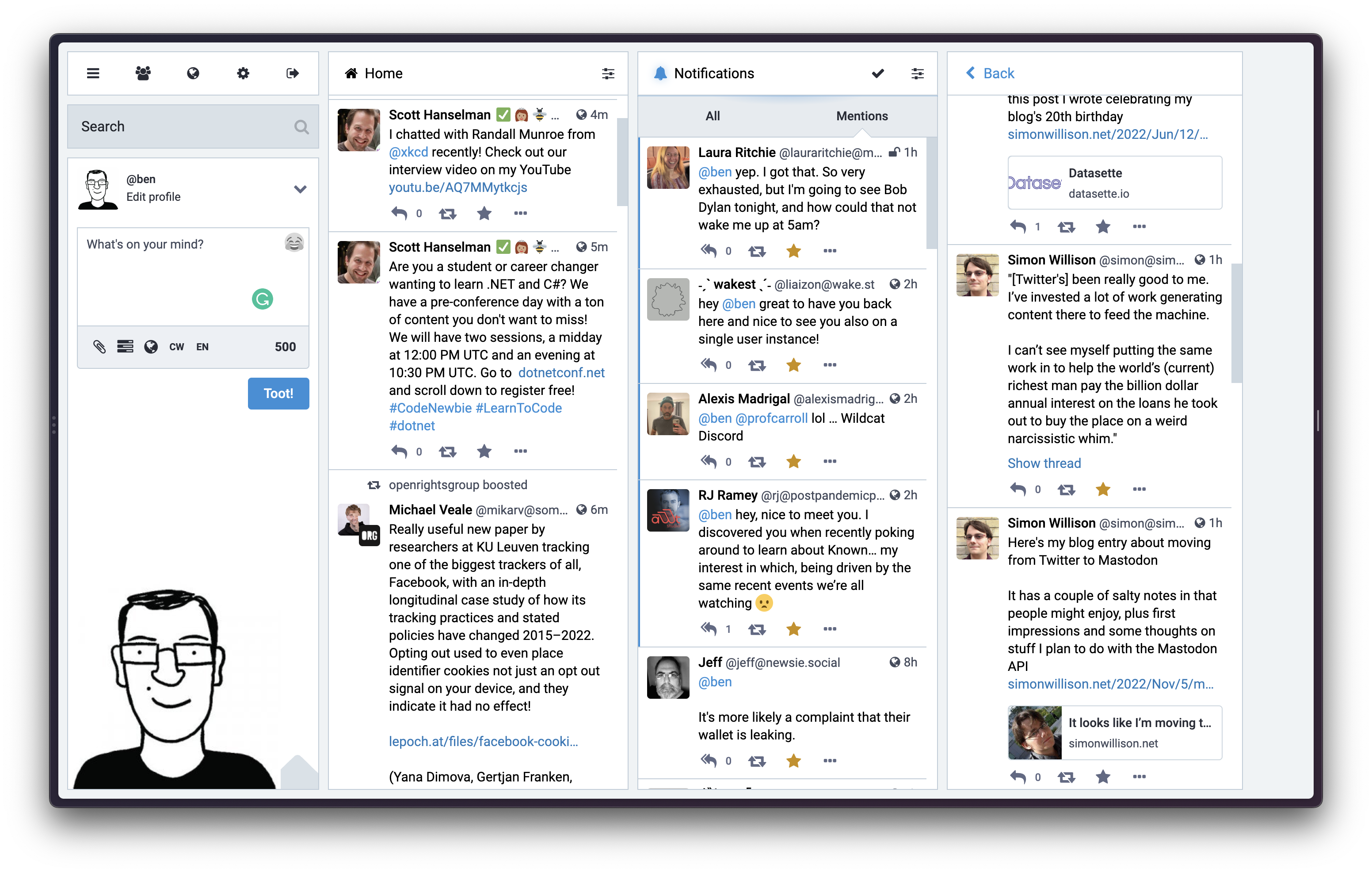

All this turns the selection of an instance when you join the network into a high-stakes choice. Does the instance have the technical resources to stay online? Does it have the social resources and insight to moderate effectively? By what rules? What are the spoken and unspoken beliefs of its owners that might affect how you post and who you can reach?

Which isn’t to say that commercial services don’t have the same problem. Clearly, they do, as can clearly be illustrated by the change in content policies at Twitter under Elon Musk compared to its previous management. Not only are content policies on commercial services notoriously imperfect, but moderation there is often undertaken by low-paid workers who frequently experience PTSD.

With a commercial service, though, you’re dealing with one service provider, rather than a patchwork, and the choice is more binary: you can take it or leave it. The fediverse gives its participants more choice, and there’s correspondingly more nuance to the decisions a user must make.

It’s unwise to dismiss these issues. They disproportionately affect people from more vulnerable communities who are more likely to experience harassment, both from admins and from other users. At their worst, they can represent real threats to physical safety; at best, they make the platform hard to trust for someone trying to use it as a basis for sharing and discussion. Mastodon has been the home for some queer communities for some time, but it’s notable that women and people of color have often had a bad experience.

I think the fediverse needs some real investment in online safety beyond what’s been done so far. Incremental approaches are probably the most feasible, rather than trying to get to the perfect thing more quickly.

Here are some suggestions as a subset of what might be useful:

A free course for moderators, with certification. Take the course - which should stress inclusion and power dynamics - in your own time. Then get a verified certification that admins can place on their Mastodon profiles. New Mastodon users could search for instances that have trained admins. Mastodon instances could actively solicit participation from potential moderators who have passed the course. (Perhaps there could be levels: for example, basic, intermediate, and advanced.)

Search that highlights moderators. The identities and beliefs of an instance’s moderators are so important that they should be placed front and center when selecting a new instance. In one recent example, I’m aware of a journalist picking an instance only to discover that its owner was notoriously transphobic. Some users might prefer instances run by women or people of color.

Standardized content policies. Content policies that can be built using pre-defined blocks, in the same way that Creative Commons licenses can be chosen based on your needs. These could be advertised in a machine-readable way, so that new users can more easily search for instances that meet their needs. Better user interfaces could be built around selection, like a wizard that asks the new user about themselves and what they care about.

Instance ratings. Right now an instance is often defederated by other instances for bad behavior, but there’s no equivalent for new users. Reviews on instances could help users pick the right one.

Shared, themed blocklists. Shared blocklists for both users and instances would make the process of removing harmful content far easier for admins. Here, if my instance blocked another instance for hosting racist content, every other instance subscribed to my racism blocklist would also block that instance.) Similarly, if I blocked a user for racism, every other user subscribed to my racism blocklist would block them too. The reverse would be true if they blocked an instance or a user, too.

These are some ideas, but experts who have worked in harassment and user security would likely have others. These are skills that are badly in demand.

Please don’t mistake this post: I’m very bullish on the fediverse. I’d love for you to follow me at https://werd.social/@ben. But particularly for those of us who have been waiting for this moment for a very long time, it’s important that we temper our excitement with an understanding of the work that still needs to happen, and that there’s much to do if we’re to create a network that is welcoming to everyone.

Share this post

Share this post