Previous birthday posts: 44 thoughts about the future, 43 things, 42 / 42 admissions, 41 things.

This post is in partial answer to Matt Mullenweg’s birthday request for everyone to blog, which is a lovely idea in its own right - happy birthday to you, too, Matt.

2024 feels like a good year for wishes.

—

One.

I wish the form of media was fully separate from its content.

For example: when I’m reading a book in bed, I want it to be text, on a screen (if it has to be a screen) that approximates ink on paper with a small reading light. But when I’m driving, that form is inappropriate: I’ll crash the car. I still want to make progress on my book, though, so wouldn’t it be great if I could flip to the audiobook for the duration of my journey? And then when I’m lying on the sofa later that evening, or sat at my desk, I’d just be able to pick up the book from that point, with a form that made sense for each of those situations. The desk-bound version might have sprawling video illustrations if it made sense for the content; if I’m lying in bed, I just need the text.

This partially exists today, and a lot of the technical prerequisites are in place, but there’s no great way to seamlessly switch between an audiobook and a book (or text and video, etc). It would be convenient; it would remove friction; it would improve accessibility.

Two.

I wish the interiors of homes were modular like computers are modular.

Today, if I want to install a washing machine, I have to make sure that the space is the right size, that I have the right electricity hookup, and that I have water and drainage. If I want to hang a picture, I have to hammer a nail into the wall or put up command strips that are likely to damage the paint when I take them off.

What if, instead of electricity plugs and water hookups and drainage, appliances sat in standard-size cradles that were pre-installed in your home? You would always know that an appliance could fit a given cradle, and that it would be provided with the electricity / water / drainage / air it needed.

What if you could hang pictures on the wall using something like MagSafe? Just hold them up and they’d snap into place, perfectly straight and aligned? What if that same mechanism could power light fittings and wall-mounted thin appliances, which also attached via magnets?

What if houses themselves were modular in this way, so that rooms and functions could easily be added or recombined, and what if these components were mass-produced in a way that lowered their cost?

What if you could attach modular power generation, like solar arrays, wind, and hydro, depending on your location’s characteristics?

Three.

I wish it was easier to bend space.

I don’t mean outer space. I wish I could turn on a portal and walk through and suddenly be in Rome, or Tokyo, or Leamington Spa. Think of it as a personal warp drive to go to the shops.

Sure, you would need to contend with timezone differences. As I write this, it’s 10:30am in Elkins Park, 7:30am in San Francisco, and 4:30pm in Paris. But honestly? I’d find a way to make it work.

One of the most defining features of the United States is its isolation. It’s harder to get to other places from here than it is from most places. Wouldn’t it be amazing to make those distances go away? You might have to resign yourself to open borders, of course, because there’d be no way to do customs and immigration if anyone could warp anywhere. But I bet we could make that work too.

(Would that lead to mass, global surveillance? How would it affect policing? Could you imagine trying to catch a criminal who could be literally anywhere in the world? Would we still need roads? So many questions.)

Four.

I wish for world peace.

If you’re rolling your eyes at me right now: fair. I don’t think most people would have read this far if I’d led with this. But, let’s be real: if you can overcome your cynicism for a moment, it would be pretty cool if there was world peace, no?

The thing is, world peace has all these prerequisites that would also have to be true. If you want world peace, you can’t occupy or exploit someone’s homeland. You can’t plunder their resources. You can’t have colonies or make opportunistic land grabs. You can’t exert your will through authoritarianism. The only way to have lasting peace is for everybody in the world to be able to have a good life, and for it to be generally accepted that this is a good and desirable outcome.

Which, in turn, means that people need to care about the welfare of their fellow humans who happen to live in other countries or lead wildly different lives to them. It implies not just tolerance, but a kind of love for people whose lives will always remain unseen to you. It means an end to nationalism; a sense of kinship with all people, everywhere.

It’s a big ask. And I don’t think we’ll get there. But I don’t think it’s necessarily too much to ask.

Five.

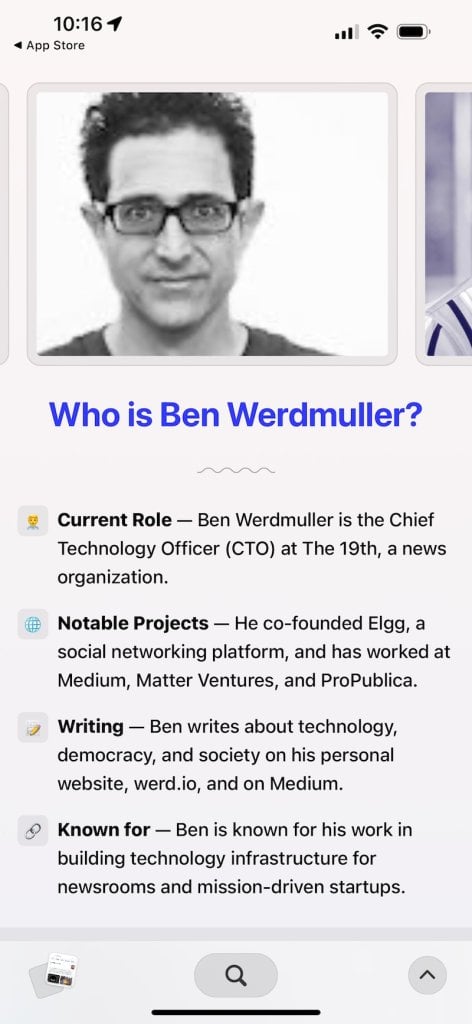

I wish there was a trustworthy, open AI engine that paid sources for their work.

Imagine you have an AI agent that is entirely yours. It tells you what you need to know (and what you might want to know), helps you interpret the world, and takes actions on your behalf. It’s a teacher, entertainer, personal assistant and thought partner.

Imagine that each business can also employ these AI agents, working behind the scenes to make their products and services better. You can interact with them via voice, text, programmatic API, and so on — whatever makes sense for the context they’re employed in.

Each agent starts with a vanilla dataset of genuinely free and open information. Then, let’s say you want to know about current events: you might add a New York Times subscription, and perhaps a subscription to a local newsroom, to your agent. If you’re a trader, you might add Bloomberg data. If you’re a pilot, you might add up to the second weather information and predictions. If you’re a venture capitalist, you might plug in market information and analysis from experts in segments you invest in.

It doesn’t happen through a private ecosystem: there’s an open standard through which AI agents discover and connect to new sources, including a mechanism for subscription payments. No one vendor controls the market; any AI engine can connect to new training data, as long as its owner agrees to the terms and pays any fees.

The journalists at the Times and the local paper, the data room at Bloomberg, the organizations providing the weather sensors and predictions, the analysts: each of these sources get paid on a subscription basis for the data used to augment each individual agent. There’s no exploitation of creators in this system; everyone is paid for their work. And through this system of plugins, users get to use an AI agent that is tailored to their needs and interests.

Six.

I wish everyone had access to healthcare.

“Having access” doesn’t just mean that it exists; it needs to be accessible. You need to be able to walk up and use it, without fear of being turned away, without fear that the financial effects of your care will be adverse, and with full bodily autonomy.

Easy-to-use, inclusive healthcare, free at the point of use. It would save so many lives. And even beyond that, it would remove a cognitive load that many people in America simply live with: a fear that something will go wrong with their health and they will ruin their lives in order to deal with it. Imagine what people could do if they weren’t afraid of having their basic needs met.

Even if you’re lucky enough to not have to worry about money, the act of having to choose health insurance, potentially figure out an HSA, pick a provider, etc, is a hassle that no-one really needs. I certainly don’t. Just make it one, continuous healthcare system.

Seven.

I think I wish we could bend time, too.

Imagine if you could hit pause and create a time bubble for yourself: a weekend temporally alone, with no requirements or restrictions looming over you. You could read a book, or do research, or bend space and go see a beautiful glacier halfway across the world. And then your bubble would end and you’d be back in the temporal world, refreshed or illuminated.

Of course, you’d continue to age in the time bubble, so you’d shorten your effective life — which is to say, the surface area of your life that interacts with everyone else. But your experiential life wouldn’t be any shorter. How you’d use this ability might depend on who you were and what you cared about; someone with loved ones or dependents might be more likely to live a temporally-aligned life, while someone without might live more of their life in a bubble. A monk might disappear into solitude and emerge - poof! - having apparently aged forty years in the blink of an eye.

It would need to be free from abuse. You can easily imagine a factory forcing its entire workforce to live in a time bubble in order to more quickly construct its products, literally working their lives away and being robbed of time with their families in the name of someone else’s profit. It would be murder, in a way.

But if it was entirely up to you? If you just needed a little more time here and there? Magic. I bet it might even make your life longer, despite everything.

Eight.

I wish we could take all the people who want to flood the web with AI-generated content and relegate them to their own mirror internet.

They wouldn’t know. They’d just be happily posting their ersatz thinkpieces at each other, giddily generating their one-sentence-per-paragraph LinkedIn updates and dumping them into the hustlenet, and we’d all be off on the real, human internet, communicating with each other in peace and tranquility.

Nine.

I wish there was a way to help build and fund end-user open source software.

Here’s how my imaginary program would work. There would be a pot of money at the center of it, managed by a foundation or an endowment of some kind, that would be ring-fenced to support software in the public interest. There would be no expectation that these projects would be self-sustaining: the fund would pay for them.

A call for applications would be made every so often. Teams could apply if they’d built an initial version. They would be expected to be able to explain the human impact of that software, and prove that it would be useful to real people. They wouldn’t get funding if they didn’t know who their users were, or hadn’t validated their product with real people.

The fund would pick six projects every cycle (perhaps every year), and guarantee a stipend that would last at least two years to work on that project. If that project continued to make a real human impact after that period, it would be renewed for another two years. In addition to releasing software, projects would be expected to transparently share their thinking, their research, and findings as they went.

Projects related to the fund, and alumni of past projects, would be expected to help each other, contribute to each other’s projects, and share their experiences. There would be a curriculum to help teams get on top of design and user experience, and to communicate effectively. The aim of the whole thing would be to make end-user open source projects more sustainable and more empathy-driven.

Ten.

I wish everyone would blog. Or write, otherwise. Or take photographs or make music or paint or sculpt or do whatever makes sense to tell their stories.

But mostly blog. I love these public journals that everyone can read. I love learning about people and what makes them excited about the world and what they’re worried about.

You should all blog. All of you. I think the world is better when everyone’s voices can be shared and heard. And I want to hear yours.

Eleven.

I wish there was a cure for dyskeratosis congenita, and for every genetic condition.

Literally one in a million people have DC. Unfortunately, I’ve been related to five of them (so far). We lost people we love to an illness that is still barely understood: my mother, my grandmother, my aunt, and two beloved cousins.

Because it’s so rare, it doesn’t achieve the funding that more common conditions receive. Some of its symptoms - pulmonary fibrosis, for example - do receive more attention, because they’re shared with other conditions. But the underlying cause remains niche.

It’s not niche to me.

And there are so many other conditions that have few sufferers overall, but where the impact on individual families is seismic. I wish there were cures. I wish that technology like CRISPR could evolve, perhaps in tandem with AI, to be able to address all of these illnesses, even when they’re rare.

Twelve.

I wish Google Maps, Apple Maps — all of the maps — took my idiosyncratic preferences into account when they drew a route.

When I ask for directions, it’s usually true that I want the roads that provide the fastest route. But sometimes, in a way that’s hard for an algorithm to predict based on logical rules, I don’t.

There’s a main road near me that leads to the Turnpike. I can take another main road to get there, or I can cut down a smaller road that takes me past the Target and the Home Depot. It’s theoretically smaller and slower, but what the mapping apps don’t know is that the route they want to take me on has a really uneven surface. I don’t want to take it; not ever. I want to go the tiny Home Depot / Target road, even though it’s worse on paper.

So, learn from me. App, you know when I ignore your advice and constantly use another road. Take the hint, please.

Because here’s the thing: I’m still relatively new to my area, I don’t always know where I’m going, and sometimes I don’t realize I’m going on the bad road until it’s too late. So I could use a little help.

Thirteen.

I wish AI-generated presenters would embrace their artificiality and really just push the boat out.

If you’re going to have a photorealistic AI newsreader, why on earth would you make them look like any other person? We have people.

The galaxy brain version of this idea is to make them into the perfect newscaster: something that could only be achieved with AI. Give them a bigger, multidimensional mouth for stronger enunciation. Give them large, resonant eyes for enhanced empathy. Give them bunny ears as a deep cut reference. Give them tentacles, because tentacles are cool.

Or perhaps you could have a sentient plasma read the news. Or the visual embodiment of the concept of gravity. Or the collective half-remembering of a song you used to know. The point is, there’s an enormous creative canvas here, and recreating an actual human being that you could have just gone ahead and hired seems like you’re leaving a creative opportunity on the table.

Fourteen.

I wish we had fully-electric, nationwide high speed rail, with satellite internet, sleeper cars, private rooms, cafes and restaurants. Let’s make them cool.

They probably couldn’t beat air travel on speed for longer distances, but they can be more comfortable, and they can let people work en route. There’s no need for them to mimic air travel in the way they do today: the space could be mixed-use, walkable, and luxurious.

Rail travel is already an experience (if you’ve never traveled coast to coast on Amtrak, you should; it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done). But it could be turned up to 11, and the speed could be turned up to 110.

Fifteen.

I wish my mother had met my son.

I wish he had her in his life.

I think about this daily.

Sixteen.

I wish we could find make all of this amazing technology without exploiting other nations, which means without conflict minerals.

We may be able to replace rare earth elements with carbon nanomaterials like graphene, which in turn can be created from raw ingredients like wood ash and even household waste. I think this is an obvious shift that’s coming down the pipe, but I wish we could be there now.

I love my iPhone; I love my electric car; I don’t want people to suffer because I own these things. I don’t want these tools to contribute to inequalities between nations. And I want everyone to be able to own one. (And I bet the relative abundance of these new materials will lead to all kinds of new amazing tech.)

Seventeen.

I wish I could find a way to be the American franchisee / importer for:

- Gregg’s the bakers: sort of the UK’s answer to Wawa or Tim Hortons (without the gas station association). This would make a killing in places like NYC, in the same way that Pret has managed to take hold. Call me a maverick, but I think America will appreciate sausage rolls. Even the vegan ones.

- Innocent Drinks smoothies. (I guess there would need to be a US version of the Blender, their impressively sustainable factory in Rotterdam.)

- I was going to say Caledonian Brewing Company beers, but it turns out they’ve been shut down since I was last in Scotland. I wish the Caledonian Brewing Company was still around. C’mon.

Eighteen.

I wish for real journalism to flourish.

I’m talking about newsrooms that speak truth to power, elevate lived experiences we might not otherwise hear about, and help us understand our world in a way that allows us to make better democratic decisions, yes, but also allows us to know who we are as a country, and understand where we are as a world.

From local police departments who act above the law because they think they’ll avoid scrutiny to governments who make deals and build strategy at the expense of entire communities, more light needs to be shone.

I’m not talking about both-sidesism here — “we went to a Nazi bar and here’s why they think their ideology is great.” — although truth be told, I think this kind of anthropology does have some value as long as you don’t fall into the trap of promoting or whitewashing their ideas or presenting them without the required context, because, at least in theory, if you can understand people, you can understand how to prevent these violent ideologies from rising again. (Too many people believe that Hitler was some kind of freakish aberration and not something that could easily happen again, even in a democratic society. Even now.)

And I’m not talking about industry puff pieces (so much tech industry journalism in particular is horrible, cheerleading stuff that celebrates wealth and power; thank the gods for the Markup, 404 Media, and Platformer) or the kind of local journalism that riles up prejudices and does nothing close to speaking truth to power.

I’m talking about the kind of journalism that shines a light on corruption, prevents peoples’ suffering, and punches up in the public interest. We need more of it. It needs to flourish. Particularly in this moment; particularly this year. In service of democracy and the well-being of the vulnerable and oppressed, in the face of widespread corruption, war, the climate crisis, and the continued rise of toxic nationalism, let a thousand newsrooms bloom.

Nineteen.

I wish I didn’t have to worry about our son’s safety.

As I write this, he’s just turned sixteen months old. He’s tall for his age: in the 99th percentile for height, looking much more like a three-year-old than the barely-a-toddler he really is.

He goes to a Jewish daycare center, and I worry about anti-semitism and what people might do to find belonging in some hateful community or to service a racist notion. Not so long ago, someone threatened the local synagogues and schools and I shot out of my office to go pick him up. The police said it was not a credible threat, but who wants to take that chance?

He also lives in America, a country where people are allowed to keep AR-15s and concealed handguns in support of entirely fictional ideas like defending themselves against a despotic government, and I wonder what someone with a gun might do. Not today, but perhaps some day: a disaffected fellow student at their school, or a misguided friend picking up a weapon that their parent owns.

I wish I didn’t have to think about this every time I drop him off, but I do. I wish I didn’t have to worry about who we know — or who he knows — might have a gun. I wish we didn’t think having these weapons around us was normal. I wish we didn’t continue to normalize them. I wish all of them were gone.

Twenty.

While we’re at it, I wish we didn’t, as a society, love cars that make it impossible to see my son from the driver’s seat.

There’s nothing wrong with small cars (except for the not-insignificant baseline of things that are wrong with all cars). Bigger cars kill more pedestrians and are far more likely to kill children. I wish we could all downsize a little.

But don’t take this the wrong way: my wish is not a criticism of people who have big cars. I know some very lovely people who have them and love them. They just scare me, is all, because I’m worried someone is going to hit my child with one, and rather than pointing fingers at anyone, I’d rather the whole ecosystem of cars was a little smaller.

Twenty-One.

I wish I could take a year off and just tinker.

I’m not sure how that would work in practice. I can’t afford to, for one thing, and I’m lucky enough to actually love my work, so I’d miss it. But it would be lovely to take some downtime and focus on creative projects.

Creative projects, for me, fall into three broad buckets:

- Writing

- Websites

- Software

Writing is exactly what you think: I have a book in progress, and I’d like to finish it. Then I’d like to write another one. I have some stories that I think are worth telling.

Websites are stand-alone projects like Get Blogging! that try to inform, entertain, or provide help.

And software is homegrown products like Known that I think other people might find useful.

What if there was a sort of angel investment agreement where someone gave you a salary for a year and took 40% ownership of whatever you created, with the promise that you’d spend the time actively trying to create things? Depending on who was offering, I’d probably take that.

Twenty-Two.

I wish something like DAOs had taken off.

A Decentralized Autonomous Organization is a leaderless organization managed through software, where decisions are made through voting and voting rights are conferred through ownership of cryptocurrency.

They’re flawed in two key ways:

- They confer more power to people who already have it, because your voting share increases with the amount of cryptocurrency you buy. People with more wealth can therefore have more say — and usually do.

- They use and depend on cryptocurrency, meaning that votes and ownership are always financial transactions.

While these flaws meant that DAOs were DOA, the idea of a leaderless organization with voting rights that are automatically enforced is interesting to me. What if we removed the financial component and overhauled the voting system to be one-member-per-vote? It might look a lot like a software-enhanced co-operative, and would be useful for everything from mutual aid to global movements to a family co-managing a house, all with enforced democracy and a careful audit trail.

Twenty-Three.

I wish we could move away from GDP as a metric for collective well-being.

Chiefly because it isn’t a metric for human well-being: it’s an imperfect measure of economic output that was designed for wartime conditions.

Amit Kapoor and Bibek Debroy in HBR:

We know now that the story is not so simple – that focusing exclusively on GDP and economic gain to measure development ignores the negative effects of economic growth on society, such as climate change and income inequality. It’s time to acknowledge the limitations of GDP and expand our measure development so that it takes into account a society’s quality of life.

So while we can talk about economic growth and hold it up as a sign of success all we want, it doesn’t at all mean that the average quality of life has gone up, or that we’ve dealt with issues like the climate crisis that will affect the quality of life of future generations.

GDP doesn’t ask if our experience as humans is improving, and it really doesn’t ask if the experience of our worst-off people is improving. I’d love to see us focus more on measuring that, rather than relying on the assumption that if the country is getting richer as a whole, everyone will see the benefit. It’s simply not true. Either we need to admit that we simply don’t create about most people’s lives, or we need to find another measure.

Twenty-Four.

I wish AI copilot for software development worked in a more literate way.

By “literate” I mean literate programming, a defined methodology where you write what you want your program to do in a descriptive, human language first, with snippets of code included almost as illustrations of their written counterparts.

Tools like GitHub Copilot let you write prompts in English, which the system then automatically replaces with an appropriate snippet of source code in the desired language. Like all AI output, it often needs a little editing, but it’s surprisingly magical.

I think AI code generation has the potential to replace software libraries in many cases. When you use a third-party library, you’re importing code that someone else has written to serve a particular function: parsing an RSS feed, say, or sorting an array of variables in a particular way. With code generation, you can prompt the engine to add RSS parsing or array sorting code, and it’ll appear as if by magic. And, unlike a library, that code will be written for you, and may be a better fit for how you want the software you’re writing to work.

There are a few limitations, beyond the usual ones that accompany all generative AI:

- While a library author will (hopefully) continuously update their code, your AI-generated code is frozen in aspic. You’ll have to update it yourself. If everyone uses AI for a particular function, it’s also possible that those engines will never update their approach to that particular problem, because there will be no new approaches to train them on.

- Your AI-enhanced code is generated prompt by prompt, rather than holistically in the context of the intention behind your whole project.

That second bullet is what I’m getting at here. What if an AI engine could look at a whole literate project in context?

The data engineer Frederick Giasson experimented with this and concluded that Copilot was context-aware within a file (or Jupyter notebook). What if it could take the whole project into account, with an accompanying UI that made specifying your applicable intentions, ethics, and values as well as your logical approach easy? Making these things explicit in the context of a body of source code, in a way that affects how that code is written and logically interpreted, is really interesting to me.

Twenty-Five.

I wish we had a pantheon of really positive science fiction stories to work from: takes where everything has worked out.

Star Trek is a little bit like that, but not really: the Federation is militaristic in nature, and while its participants have been drawn from disparate worlds and contexts, its culture is pretty homogenous. I don’t know that that’s what we should be aiming for.

Most of the science fiction I’ve watched or read over the last few years in particular has been willfully dystopian. Even Doctor Who, which is more fantasy than science fiction to begin with but plays with notions of whimsy and radical inclusion, has both feet set in the aftermath of a great war. The science fiction I’m writing — in part about the idea that the thing that will bring us down in the climate crisis is not the crisis itself but our need to profit from it — crosses that line too.

The problem is, as Charles Stross pointed out in Scientific American recently:

Billionaires who grew up reading science-fiction classics published 30 to 50 years ago are affecting our life today in almost too many ways to list: Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars. Jeff Bezos prefers 1970s plans for giant orbital habitats. Peter Thiel is funding research into artificial intelligence, life extension and “seasteading.” Mark Zuckerberg has blown $10 billion trying to create the Metaverse from Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash. And Marc Andreessen of the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz has published a “techno-optimist manifesto” promoting a bizarre accelerationist philosophy that calls for an unregulated, solely capitalist future of pure technological chaos.

We need to be able to imagine a really great future in order to get there. I think we’ve lost that muscle. We’ve ceded optimism to people who seek to create an adverse future. It’s easy to see how we got here — the world often feels oppressive — but it’s imperative that we re-find the sunlight.

There are positive science fiction movements: solarpunk, for example. I’d love to see more; I’d love to read more. Perhaps write more?

Twenty-Six.

I wish I was better at seeing my friends. Or, at least, keeping up with them.

I’ve never regretted moving to the US — supporting my terminally ill mother was a very good reason — but I’ve missed a lot of people. I made a lot of friends in the twelve years I’ve been here, and moving from California to Pennsylvania was almost the same level of severance, although the pandemic has made us all far more used to hanging out online.

There was a time, when I was much younger, when I could send a text that read:

Pub?

And an hour later I’d be hanging out with friends, having a few drinks (alcoholic and otherwise), talking about anything and everything. I really deeply miss being able to do that.

Twenty-Seven.

I wish for everyone I love to be healthy.

I wish for everyone I love to be happy.

I wish for everyone I love to be here.

Twenty-Eight.

I wish every software development team stopped to ask:

- Who, exactly, are we building this for?

- Is it the right thing?

- Why do they need it?

- How do we know?

- If we are successful, who will be impacted?

- How can we ensure that as many people as possible see the benefits?

There’s an idea that software is somehow outside of the human sphere, a world of discrete logic and objectivity. It’s not, and the more we acknowledge and internalize how human software actually is, the more useful and world-positive it becomes.

You don’t build software for everyone, because that’s the same as building it for no-one. You build it for specific people, serve their needs deeply, and expand from there. How do you know their needs? Because you know them, not as abstracted-away personas or vague market notions, but as real, concrete human beings who you’ve met with and understood.

Building useful software is an exercise in engineering, of course. But more than that, it’s an exercise in empathy, of human relationships, and of community. I wish that was universally acknowledged and built directly into both engineering processes and team cultures by default.

Twenty-Nine.

I wish I’d been to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This one seems particularly fixable, right? I’ve lived in the Greater Philadelphia area for a year. One of the best art museums in the country (maybe the world) is downtown. I think art is important; I like art; art makes me happy. I should have been by now.

But, of course, life happens, and there’s always something more important to do. There are chores to do for the baby, and things to do for the house, and admin stuff more generally, and work, and we need groceries, and there are other, closer trips to be had. There are so many things. And before you know it, it’s been a year, and this thing that I knew I wanted to do before I got here remains undone. And then before I know it, it’ll be another year, and another, and I’ll have blinked and life will have flowed all the way through my fingers.

It’s not really about the Philadelphia Museum of Art, of course. But it is about intentionality, and about self-care, and prioritization.

Maybe I’ll go next weekend. Unless something comes up.

Thirty.

I wish I could sing and play guitar.

My cousin Noah wrote these lovely songs for his wife, for his children, for his cousins. Music was such a core part of his life, and it became a core part of the lives of the people closest to him.

I love that spirit, and I wish I could embody that in some way. It’s not about a particular artistry or form; it’s about being able to convey the underlying emotion. In a very real way, it’s about love.

I miss Noah. I wish he was here.

Thirty-One.

I wish we could nudge our rhetoric from “trust experts” to “work with experts”.

The “trust experts” line comes from the pandemic, when skeptics and anti-vaxxers were urged to trust the scientific advice we were being given. In that context, and to that audience, I think it’s obviously right: the level of misinformation was intense, and intensely politicized, which led to real loss of life.

On the other hand, if we’re talking about smart people engaging in their own lines of informed inquiry, I think it’s safe to expand the discourse. Experts are a resource, and their expertise deserves respect. But there can also be edges to their expertise, and engaging with them may expand the knowledge frontier for both of you.

A very concrete example in my own life was my mother’s idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which was rapidly re-labeled to familial pulmonary fibrosis. “Pulmonary fibrosis” is the name for the symptom, not the cause; “idiopathic” means the cause was unknown. We worked with the doctors, and did our own research, read scientific papers, and arrived at the conclusion that it was dyskeratosis congenita, which then informed the hospital’s own line of inquiry. Ultimately, this was proven to be correct, but we might not have arrived at this understanding (at least on the same timeline) if we hadn’t done our own work, and if the experts hadn’t been open to working with us.

Science can be a conversation. I think medicine certainly should be. It has to be one grounded in science and fact, of course: it’s hard to have a conversation with someone who thinks a medicine can make you magnetic or that it’s part of a mass conspiracy. But I think sometimes we can be a little too hard-line in our discourse about who should be listened to and who should not.

Thirty-Two.

I wish civilization was further along than it is.

I’m typing this in my house, which is really four walls in the dirt, themselves made of different kinds of mud and stone. A great deal of heat is escaping through the windows, which are made of liquid sand that have been reshaped into thin, brittle panes.

I have to worry about whether the food I eat is good for me, and who picked it, or how it was gathered or killed. Outside in the drive, there’s a car that runs on condensed million-year-old plants, and there’s a car that runs on electricity. Both cars contain rare elements that were mined in parts of the world that have been subjugated by my part of the world so that the cars and computers and batteries can be made.

We’ve come so far, but there’s so much left to achieve. I wish we were there. I wish all food was good for me and ethically sourced, and that all my useful devices were made of good things that harmed nobody, and that everybody had the ability to own one and nobody wanted for any necessities at all except to further the collective experience of being human.

It seems silly that we have to worry about war and poverty and inequality and exploitation and hatred. We don’t need those things. Some of them were a part of early civilization but that doesn’t means they need to continue for us to succeed. That’s the sunk cost fallacy in action right there. We can build something new. I wish we would. I want to live in the future.

Thirty-Three.

I wish movies would be available on streaming on day one.

You’re probably not going to get me into a theater anytime soon. Don’t get me wrong: I love movies and the theater experience of seeing something in a room with lots of other people. It can be magical. But worrying about the pandemic, and worrying about finding a babysitter, kind of take the shine off.

I want to sit in my living room, under my fluffy blanket, with my own food and my own drinks, in the knowledge that I’m probably not going to get a serious infectious disease and that I can pause the movie if the baby wakes up.

I’d still like the option of going to the theater. Again: theaters are great. But right now, they’re not things that fit in well with my life.

I’m not alone. Just let us stream. We’ll pay.

Thirty-Four.

I wish the internet was exactly the same for everyone in every location, and that every website was equally as fast.

I wish there was full privacy and freedom from tracking built into the platform.

I wish the major conduits for sharing and learning online were collaboratively built rather than privately owned.

I wish the web in particular was about sharing and advancing knowledge, connecting people with each other’s lived experiences, supporting democracy, and improving our collective well-being.

I wish it was owned by everybody and nobody.

I wish everybody had access.

Thirty-Five.

I wish to only work in organizations that value DEI for the rest of my career. Although every organization is different, and the experience of working at them varies, it’s always a good sign.

I wish inclusion was universally seen as the obviously good thing it is, and that it was understood to be a prerequisite for responsibly building any company or institution.

Thirty-Six.

I wish there was software that could take a look at your life and show you different versions of it.

Think about those photography AI tools: things like FaceApp that, with a click of a button, can tell you what you’d look like if you were the opposite gender, or older, or younger, or a little more masculine, a little more feminine, a little better or worse looking. With a click of a button they can make you smile like you mean it, or give you a more expensive haircut.

Imagine you could push a button that said, “show me a version of myself where I was truly happy.” The software would examine your life, think for a little bit, and then give you a complete picture: a photograph of the happiest version of yourself, and a description of all the little details that add up to you. With another button, perhaps it could offer you a diff: here’s all the things that are different. And with a third, here’s how you can get to that version of your life from this one.

You could ask it what your life would look like if you were wealthy, or if you had no money at all, or if you lived alone or had a big family. It could shard you into fragments and possibilities and you could map all the different yous until you found one that looked right.

I wonder if, given the map, you’d actually follow the steps and make it to this other, hypothetical version of yourself, or if you’d stay put, safe in the knowledge that actually, you’re good where you are. I wonder, if you did take those steps and made it there, if you’d actually be in any way happier or more content, or if the knowledge of your original life and what you’d lost would invalidate it all: if those other selves are only valid in their vacuums.

I wish the software existed so we could know what was possible within our own lives. I don’t think I’d want to take the steps and get there. But the perspective? Perspective always changes everything.

Thirty-Seven.

I wish for us to be able to give our son every opportunity, every life experience, every freedom, every possible gesture of love and care.

I would love for him to have broad horizons, a non-conformist attitude, a global outlook, an inclusive heart, and a progressive mind. I would love for him to understand his radical interdependence with every other person rather than wild independence. We’re going to love him whoever he chooses to be. We’re going to show him the world.

Thirty-Eight.

I wish that everybody had the right to full self-determination for their identity.

I wish that the people I know who have had to fight so hard just to be themselves could relax, safe in the knowledge that they were safe from discrimination and harm.

I wish they knew that the identity they worked so hard to establish is how they would be known, without question or argument.

I mean, it’s just common decency.

Thirty-Nine.

I wish our personalities weren’t so siloed.

Just because I encounter someone in a business context, it doesn’t mean I only want to see the business facet of who they are. I want to learn how they think about the world: what kind of art they love, how they’re weird, what they’re proud of.

I feel that way about personal websites a lot: they tend to stick to the same form and topics. They couldbe jumping from topic to topic, exploring what they’re excited by, describing what makes them feel alive. They could be experimenting with form: a graphic novel here, spoken-word poetry there. Everyone’s public persona is the above-water tip of an iceberg of creativity and excitement that we mostly don’t let anybody else see. But that’s the stuff that really makes us human; it’s what makes us interesting and unique.

I know this is complicated for a hundred reasons, not least because it’s easier for people with privilege than people from more vulnerable or underrepresented contexts, but I feel like if we were all more comfortable to share more of ourselves, so much more would be possible. If we were more uninhibited to share our creative ideas with each other, we might see more interesting collaborations; innovations that otherwise would never have been possible. If we increase the surface area of our possible connections, we increase the chances that one of those connections hits home so deeply and meaningfully that it changes our lives.

I want you to feel free to share more of you. I want to feel free to share more of me. Let’s make a pact to give ourselves the freedom to be human, to experiment with form and creativity, to make things that don’t work, to just go for it and see what happens.

I don’t think we can do that if the form of our communications is limited to a small text box owned by some company somewhere, where the user experience has been optimized and averaged-out in order to maximize engagement and revenue. I think we need to own our communications again, stop sanding off our edges or letting people with a profit motive sand our edges off for us. Let’s be weird. Let’s whisper and shout and sing. Let’s try new shit. I wish we could all stop being beige and start being our full selves with each other. I wish we could stop trying to fit ourselves into boxes that other people have made for us. Let’s burn the boxes to the fucking ground.

Forty.

I wish I could undo many things. Just strip them from reality.

I also wish I could re-do many things. As in, have a do-over. Take another run at them and hopefully do better.

And I wish I could re-experience many things. Just live through them again, savoring every second, because I know I’ll never get those moments back, that they are perfect and fleeting and gone.

Forty-One.

I wish to be a better partner. I wish to be a better parent. I wish to be a better person. (I’ll keep working.)

Forty-Two.

I wish for a climate in balance that can support every person and every living thing on the planet.

There are so many prerequisites; so many things that have to radically change. I wish for every single decision and dramatic transformation it’ll take to get there.

Forty-Three.

I wish for mutual respect: for ourselves, for our fellow people, for the world and the ecosystem around us, regardless of proximity or origin.

Forty-Four.

I wish for community. I wish for collective empowerment. I wish for inclusion. I wish for a broad awareness of the interrelatedness of all people and all things.

Forty-Five.

I wish to continue living. I wish to live more: a long life that is vibrant, unique, kinetic, and full of light. I wish that for every single one of us.

Share this post

Share this post