Without serious intervention, newsrooms are going to disappear. Changes to social media and the advent of generative AI threaten their businesses and the impact of their work. They need to own their online presences outright and build direct relationships with their communities—and they need to do it now.

Social media audiences are plummeting. Less than 35% of internet searches lead users to click on a website. The views and engagement that newsrooms depend upon to survive are disappearing.

It’s happening quickly. Semafor’s Max Tani reported recently:

Washington Post CEO Will Lewis is introing the paper’s new “Build It” plan today. In a meeting with staff, he noted that the paper lost $77 million over the past year, and saw a 50% drop off in audience since 2020: “To be direct, we are in a hole, and we have been for some time."

Addressing this challenge will require radical changes to how newsrooms invest in and build technology.

In this post, I’ll attempt to describe the challenges in more detail and then discuss how they can be more adequately addressed.

Some context: my move into news

I’ve recently gained a new perspective on these challenges. For over a decade, I’ve worked adjacent to news and journalism. I’ve seen the industry as an engineer, startup founder, product lead, investor, and advisor. More recently, I decided I could be more useful in directly leading technology efforts inside newsrooms. It’s been eye-opening, rewarding work.

My experience alongside news was diverse. I built product for newsrooms, founded a startup used by public media, invested in early stage media startups, and have taught human-centered product design to teams at organizations like the New York Times and the Associated Press, as well as at institutions like the Newmark School of Journalism and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. I’ve built software, founded, grown, and supported startups, and taught product design to some of the biggest names in journalism.

My immersion inside newsrooms has been much more recent. ProPublica investigates abuses of the public trust by government, businesses, and other institutions. I’ve worked on technology strategy for the last year, first as a contractor, and now as its Senior Director of Technology. Before that, I was the first CTO at The 19th, which reports on the intersection of gender, politics, and power.

I made this career shift at a pivotal moment for journalism—though it seems every moment for journalism over the last fifteen years has felt pivotal. The industry has struggled to weather the seismic shifts brought about by the internet, which have impacted its business, the state of our politics, and public discourse. It’s been a struggle for decades.

The audience threat

It’s getting harder and harder for newsrooms to reach their audiences — and for them to sustain themselves.

I’ve often remarked that journalism treats the internet as something that happened to it rather than something it can actively shape and build, but it at least had some time to adjust to its new normal. The internet landscape has been largely static for well over a decade — roughly from the introduction of the iPhone 3G to Twitter’s acquisition by Elon Musk. People used more or less the same services; they accessed the internet more or less the same way. Publications and online services came and went, but the laws of physics of the web were essentially constants.

Over the last year in particular, that’s all changed. Shifts in the social media landscape and the growing popularity and prevalence of generative AI have meant that the rules that newsrooms began to rely on no longer hold.

At their heart, online newsrooms have a reasonably simple funnel. They publish journalism, which finds an audience, some of which either decide to pay for it or view ads that theoretically cover the cost of the work. Hopefully, they will make enough money to publish more journalism.

This description is a little reductive: there are lots of different revenue models in play, for one thing. I’m particularly enamored with patronage models that allow those with the means to support open-access journalism for anyone to read freely. Still, some are entirely ad-supported, some are sponsored, and others are protected behind a paywall (or some combination of the above). For another, journalism isn’t always the sole driver of subscriptions. The New York Times receives tens of millions of subscribers from its games like Wordle and Connections, as well as its Cooking app.

Still, there are two pivotal facts for every newsroom: their work must reach an audience, and someone must pay for it. The first is a prerequisite of the second: if nobody discovers the journalism, nobody will pay for it. So, reaching and growing an audience is crucial.

For the last decade and a half, newsrooms have used social media and search engines as the primary way to reach people. People share stories across social media—particularly Facebook and Twitter—and search for topics they’re interested in. It’s generally worked.

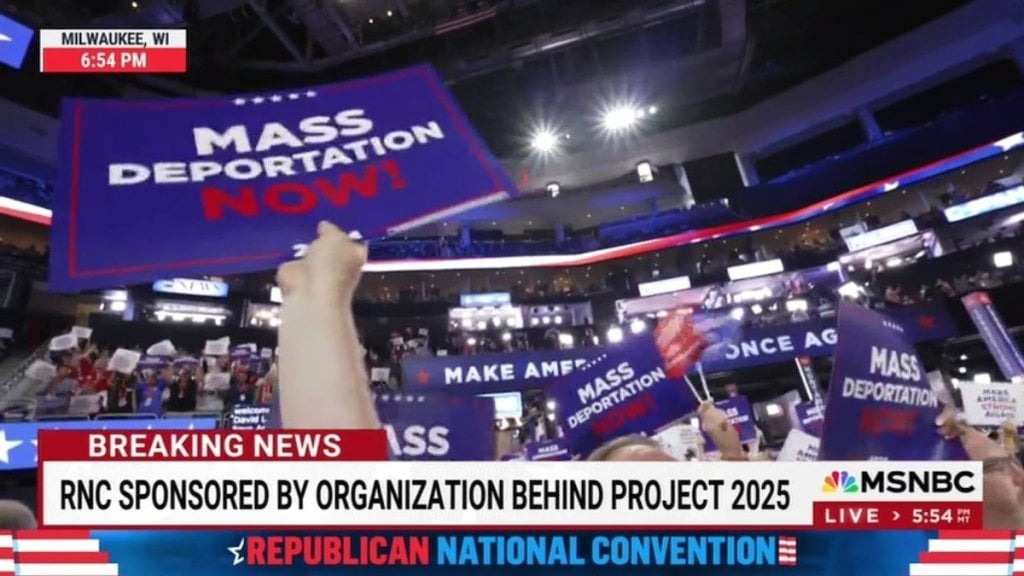

Over the last year, social media has radically fragmented. Twitter transformed into X under its new management; users began to flee the platform in the face of more toxic discourse, and active use plummeted. Facebook is slowly declining and referrals to news sites have fallen by 50% over the last year. Instagram is not in decline. Still, it’s harder to post links to external sites there, which means that while newsrooms can reach users, they have more difficulty converting them to subscribers.

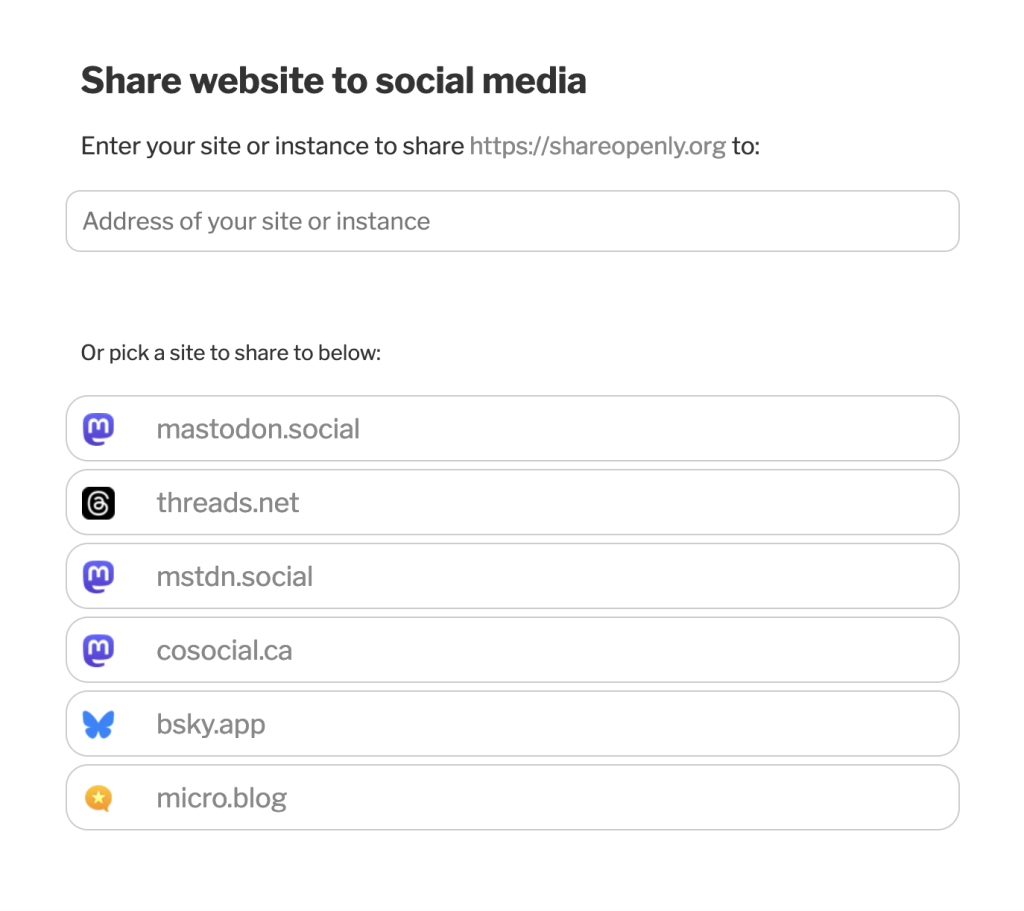

On top of these changes, we’ve also seen the rise of Threads, Mastodon, and Bluesky, as well as a long tail of other social apps, platforms, and forums on which to reach people. Audiences on social media used to be found in a very small number of places and are now spread out across very different platforms. The fediverse and AT Protocol also yield different problems: which instance should a newsroom choose to make its home? How can it measure engagement in what it posts in a decentralized system so that it knows what’s working and where it should continue to invest its meager resources?

Much has been written about newsrooms’ inability to move away from X even as it has become a hotbed of white supremacy and far-right rhetoric. The honest truth is that it still drives significant traffic to their websites, and in an environment where traffic referrals are dropping overall, intentionally further deepening the traffic shortfall is understandably not a career risk newsroom leaders are willing to make.

Social media isn’t the only way newsrooms are finding it harder to find an audience. Even search engines, long the stalwarts of the web, are moving away from referring traffic.

As search engines move to make AI-driven answers more prominent than links to external websites, they threaten to reduce newsroom audiences, too. More than 65% of Google searches already ended without a click to an external site. Now, it’s planning to roll out AI-driven answers to over a billion people. It’s not that other links are going away entirely. Still, because AI answers are the most prominent information on the page, clickthroughs to the external websites where the answers were found initially will be significantly reduced.

A similar dynamic is at play with the rise of AI services like ChatGPT, emerging as stiff competition for search engines like Google. These services answer questions definitively (although not always correctly), usually with no external links on the page. ChatGPT could learn from a newsroom’s articles and display information gleaned from an expensive investigative story while never revealing its source or allowing readers to support the journalism.

Generative AI models seem like magic: they answer questions succinctly, in natural language, based on prompts that look a lot like talking to a real human being. They work by training a neural network on a vast corpus of information, often obtained by crawling the web. Based on these enormous piles of data, AI engines answer questions by predicting which word should come next: a magic trick of statistics empowered by something close to the sum total of human knowledge.

That’s not hyperbole. It’s not a stretch to say that OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini were trained on most of the internet, including websites, published books, videos, articles, art, science, and research. They couldn’t function without this data — but, ironically, they rarely credit their sources for any of it. Users see the benefit of fast answers; the sources of that information are starved of oxygen.

We’re at the foothills of both changes: social media is likely to fragment further, and generative AI will become even more prevalent as it becomes more powerful. Newsrooms can no longer rely on their old tactics to reach their audiences, and they will need to build new tactics that take these trends into account if they hope to survive.

Some models are more resilient than others

The 19th’s Alexandra Smith recently wrote about the state of play in Columbia Journalism Review:

In our current reality, journalism exists in various formats splintered across platforms and products. People are just as likely to get their news on Instagram as from a news website. It no longer makes sense to rely primarily on measuring readership by traditional website metrics.

This is a depressing fact if you rely on paywalled subscriptions or ad impressions. Nobody’s looking at your ads if they’re consuming your journalism off-platform, and how can you possibly get someone to subscribe if they never touch your app or website? Instagram and TikTok don’t have built-in subscriptions.

Over the years, many people have suggested micropayments — tiny payments you make every time you read a news article anywhere — but this depends on everyone on the web having some kind of micropayment account that is on and funded by default and the platforms all participating. It’s a reasonable idea if the conditions are right, but the conditions will never be right — and, like subscription models, it shuts out people who can’t pay, who are often the people most in need of public service journalism to begin with.

For newsrooms like The 19th, the picture is much rosier: like most non-profit newsrooms, it depends on donors who support it based on its journalistic impact. (The same is true of ProPublica, my employer.) That impact could occur anywhere, on any platform; the trick is to measure it so donors can be informed. Alexandra developed a new metric, Total Journalism Reach, that captures precisely this:

Right now, it includes website views; views of our stories that are republished on other news sites and aggregation apps, like Apple News; views of our newsletters based on how many emails we send and their average open rates, reduced for inflation since Apple implemented a new privacy feature; event attendees; video views; podcast listens; and Instagram post views.

This is clearly valuable work that will help newsrooms like The 19th prove their impact to current and potential donors. The quote above doubles as a useful example of the places The 19th is reaching its audience.

It’s worth considering how these might change over time. Some of the media Alexandra describes are inside The 19th’s control, and some are less so.

Supplier power

In his classic piece How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy, Michael Porter described five forces that shape competitive strategy. One of them is supplier power: the ability of providers of essential inputs to a business to exert influence over the organization. If suppliers to the industry have too much power — because there are few alternatives, for example — they can effectively force the company’s strategy by raising costs or enforcing adverse policies.

Newsrooms’ platforms for reaching their audiences, such as social media and Apple News, currently have outsized supplier power over the journalism industry. As a result, the industry is disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of business decisions made by the owners of those platforms.

In April, Instagram introduced a new automatic filter, switched on by default, to remove political content, which affected many newsrooms, and illustrates the kind of changes service providers can make on a whim.

Newsrooms on Apple News tend to see a multiple of the number of reads they see on their websites, but Apple could pull the product tomorrow. Even today, the number of views you get highly depends on which stories the Apple News team chooses to highlight. Ads in publications on Apple News need to use Apple’s ad network. It’s a closed shop. Apple News is only successful because it comes installed by default on Apple devices; hundreds of similar news aggregators have all failed to survive in their own right. It’s a precarious place to hang your hat.

We’ve already discussed the impact of search engine design decisions like prioritizing AI over click-through rates. Only one search engine is prominent enough to have disproportionate supplier power: a position Google has bought by spending over $21 billion a year to be the default search engine in every web browser.

However, not all conduits to readers have this outsized supplier power as a feature. Social media platforms, search engines, and news aggregators are all run by wealthy individual companies like X, Meta, Google, and Apple, who have the potential to exert their power. If you choose to leave them for any reason, you’re also leaving behind the relationships you’ve built up with your audience there: there’s no audience portability.

In contrast, email, podcasts (real podcasts, not the single-platform kind where you ink an exclusive deal with Spotify or Audible), and the web are well-used methods to reach audiences that aren’t owned by any platform. There are certainly market leaders for each communication type. Still, each is based on an open protocol that no single company controls — which means, for those methods, no supplier can exert adverse supplier power. If one service provider misbehaves, you can simply switch to another without losing functionality. You can bring your audience with you. They’re safer methods, as long as enough readers want to be reached in those ways.

That’s why so many publications have focused their strategies on their email newsletters. Everyone already has an email address, and (barring technical difficulties) if a publisher sends a subscriber a message, they’re guaranteed to receive it. Moreover, people engaged enough to hit the “subscribe” button are far more likely to convert to donors or upgrade to a paid subscription.

Newsletters, unfortunately, are also in decline. Open rates have fallen over the last decade; Gmail’s dominant position and aggressive filtering have made it harder for newsletters to be noticed; there’s more competition for attention. There aren’t any great ways for new readers to discover newsletters — those subscription pages are subject to the same internet traffic dynamics as articles. It’s getting harder and harder to direct new visitors to subscribe, which is why we see more overt “please subscribe” popup overlays on news sites. The focus has needfully shifted to converting more existing subscribers into donors or customers rather than widening the funnel and finding more newcomers.

Newsrooms need alternative media that allow them to make direct connections with their audiences. These media must be free from undue supplier power and have a large base of existing users that can be tapped into.

So what else is out there?

The answer is not much. Yet.

The innovation squeeze

Most non-profit newsrooms have tiny technology teams. The 19th, when I was CTO, had two engineers in addition to me; ProPublica has four. (Other interactive developers work on standalone stories but don’t address platform needs.) In contrast, I led a team of twenty-two engineers at the last startup I worked at, and we had over a hundred at Medium.

To bridge that gap, there is a small community of digital agencies that make supporting newsroom platform needs a core part of their business. Probably the most famous are Alley and Upstatement, but there are around a dozen more that are actively used by newsrooms.

They do beautiful work and are an excellent way for a newsroom to start strong with a modern brand and a well-functioning web platform. I strongly recommend that a new newsroom consults with them.

There is an emerging dynamic, though, where the technology vision for a newsroom is outsourced to the agencies. As we’ve discussed, a newsroom’s success and impact depend highly on core internet technologies like the web and email. Newsrooms quite reasonably spec and build a platform based on what will work well today. However, because the vision and expertise for harnessing the internet lie with the agencies, they don’t have any meaningful technology capability for innovating around what will work well tomorrow.

Newsrooms absolutely need to focus on today. That’s an obvious prerequisite: they must meet their audiences, subscribers, and donors where they’re at right now. However, they also need to be aware of what is coming down the road and prepared to experiment with, engage with, and potentially help shape new technologies that could impact their businesses in the future. If the internet changes, they need to be ready for it. To reference an overused Wayne Gretzky quote: you need to skate to where the puck will be, not where it is right now.

Nobody knows for certain where the puck will be. That means newsrooms need to make bets about the future of technology — which, in turn, means they must have the capacity to make bets about the future of technology.

Most newsrooms already have technical staff who maintain their websites, fix broken platform stacks, and build tools for the newsroom. These staff must also highlight future business risks and allow them to experiment with new platform opportunities. In a world where newsrooms rely on the internet as a publishing mechanism, technology expertise must be integral to their strategy discussions. And because technology changes so quickly and unpredictably, maintaining the time, space, and intellectual curiosity for experimentation is critical.

Nothing will work, but anything might

Experimentation doesn’t need to be resource-intensive or time-consuming. Alongside in-house expertise, the most important prerequisite is the willingness of a newsroom to test: to say “yes” to trying something out, but being clear about the parameters for success, and always rooting success or failure in a concrete understanding of their communities.

I’ve written before about how, if the fediverse is successful, it will be a powerful asset to media organizations that combines the direct relationship properties of email with the conversational and viral properties of social media. At the same time, there’s no doubt that the network is relatively small today, that the experience of using Mastodon falls short of corporate social networks like the Twitter everyone remembers, and that features like blocking referrer data makes life much harder for audience teams. There are lots of good reasons for a resource-strapped management team to say “no” to joining it.

At the same time, because it has the potential to be interesting, some newsrooms (including my employer) are experimenting with a presence. The ones who make the leap are often pleasantly surprised: engagement per capita is dramatically higher, particularly around social justice topics. Anecdotally, I discovered that posting a fundraising call to action to the network yielded more donations than from every other social network — combined.

It’s worth looking at Rest of World’s “More Ways to Read” page — a massive spread of platforms that runs the gamut from every social network to news apps, messaging platforms, audio, newsletters, and RSS feeds. The clear intention, taken seriously, is to meet audiences where they’re at, even if some of those networks have not yet emerged as a clear winner. All this from a tiny team.

However, experimenting isn’t just about social media. It’s worth experimenting with anything and everything, from push notifications to website redesigns that humanize journalists to new ways for communities to support the newsroom itself.

On the last point, I’m particularly enamored with how The 19th allows members to donate their time instead of money. Understanding that not everyone who cares about their mission has discretionary spending ability, they’re harnessing their community to create street teams of people who can help promote, develop, and share the work in other ways. It’s brilliant — and very clearly something that was arrived at through an experimental process.

I learned a formal process for human-centered experimentation as a founder at Matter, the accelerator for early-stage media startups, which changed the way I think about building products forever. A similarly powerful program is now taught as Columbia Journalism School’s Sulzberger Fellowship. If you can join a program like this, it’s well worth it, but consultants like Tiny Collaborative’s Tran Ha and Matter’s Corey Ford are also available to engage in other ways. And again, the most important prerequisites are in-house expertise and the willingness to say “yes”.

To achieve this, they must shift their cultures. The principles of experimentation, curiosity, and empathy that are the hallmarks of great journalism must also be applied to the platforms that power their publishing and fundraising activities. They must foster great ideas, wherever they come from, and be willing to try stuff. That inherently also implies building a culture of transparency and open communication in organizations that have, on average, underinvested in these areas. As Bo Hee Kim, then a Director of Newsroom Strategy at the New York Times, wrote back in 2020:

Companies will need to address broader issues with communication, access, and equity within the workplace. Leaders will need to believe that newsroom culture has a bigger impact on the journalism than they understood in previous years — that a strong team dynamic is as important as their sharp and shiny stars. Managers are key to this transition and will need to reset with a new definition of success, followed by support and training to change.

Gary P. Pisano in Harvard Business Review:

Too many leaders think that by breaking the organization into smaller units or creating autonomous “skunk works” they can emulate an innovative start-up culture. This approach rarely works. It confuses scale with culture. Simply breaking a big bureaucratic organization into smaller units does not magically endow them with entrepreneurial spirit. Without strong management efforts to shape values, norms, and behaviors, these offspring units tend to inherit the culture of the parent organization that spawned them.

Creating an innovative culture is complex, intentional work. But it is work that must be done if news organizations are to innovate and, therefore, survive.

Conclusion

The internet is changing more rapidly than it has in years, creating headwinds for newsrooms and jeopardizing independent journalism’s viability. We need those organizations to exist: they reduce corruption, inform the voting public, and allow us to connect with and understand our communities in vital ways.

These organizations must own their digital presence outright to shield themselves from risks created by third parties that wield outsized supplier power over their business models. They must build direct relationships with their communities, prioritizing open protocols over proprietary systems. They need to invest in technology expertise that can help them weather these changes and make that expertise a first-class part of their senior leadership teams.

To get there, they must build an open culture of experimentation, where transparency and openness are core values cemented through excellent, intentional communication. They must be empathetic, un-hierarchical workplaces where a great idea can be fostered from anywhere. They must build a mutual culture of respect and collaboration between editorial and non-editorial staff and ensure that the expertise to advise on and predict technology challenges is present and well-supported in-house.

Experimentation and innovation are key. Newsrooms can discover practical ways to navigate these challenges by testing new strategies, technologies and mindsets. The road ahead is challenging, but with strategic investments and a forward-looking approach, newsrooms can continue to fulfill their vital role in a well-functioning democratic society. The best time for action was ten years ago; the second best time is now.

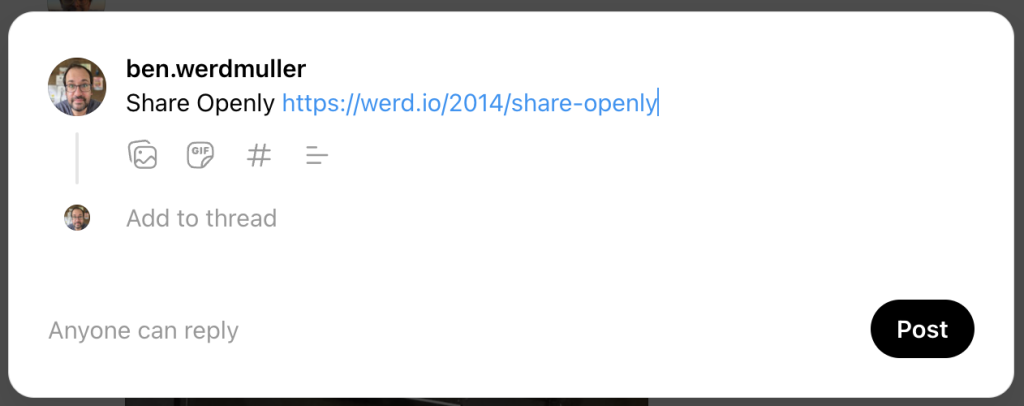

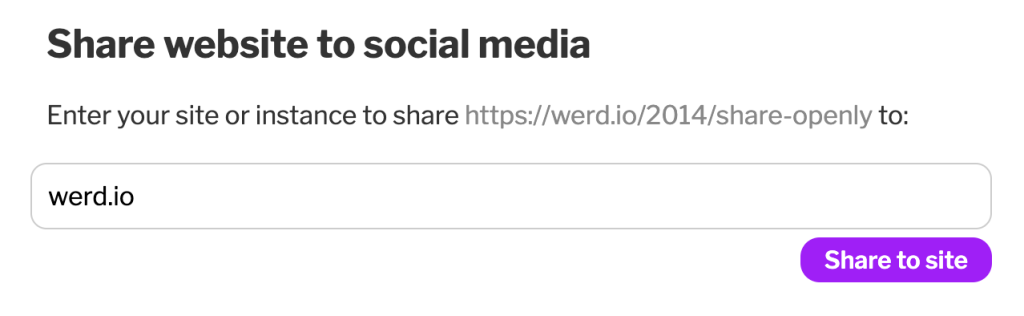

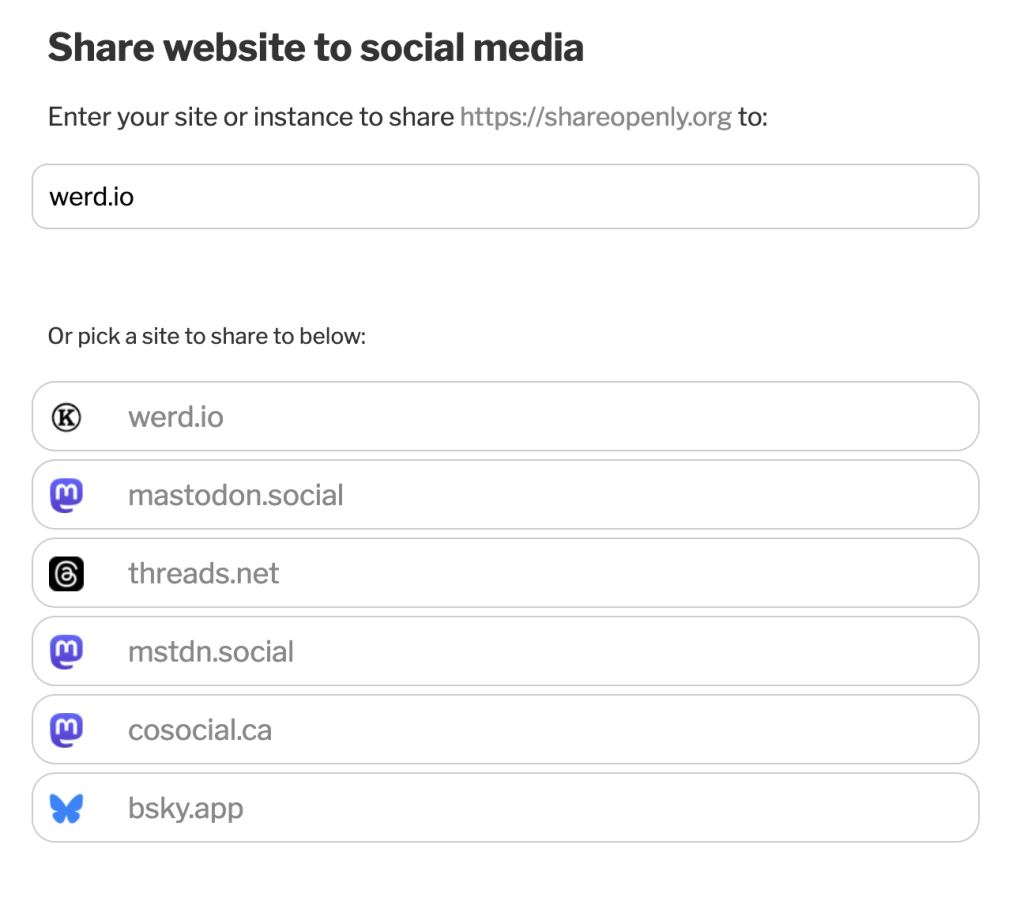

Share this post

Share this post