Previous birthday posts: 45 wishes, 44 thoughts about the future, 43 things, 42 / 42 admissions, 41 things.

One. I lie in bed as Ma read Dodie Smith’s The Hundred and One Dalmatians to me. It was the fifth, and last, straight time; after this, she would finally put her foot down. Outside, in the Oxford dusk, the neighborhood dogs speak to each other over fences and hedges, the starlight barking in full force. Occasionally, a bird lands on the spiraling wrought iron fire escape outside.

It’s an old book, and the Romani people are not treated well in it. Revised versions are available. And, of course, the Disney versions.

Two. Nobody seems to want to adapt the anti nuclear war science fiction sequel, though, the cowards.

Three. I borrow Constellations: Stories of the Future from the library for the third time: a hardback book in a protective plastic sleeve full of stories that seem almost illicit. One of the stories, Let’s Go to Golgotha! is about a time-traveling tourist agency; the participants slowly realize that the crowd condemning Jesus to the cross is entirely made up of people from the future. Beyond Lies the Wub was Philip K Dick’s first short story; a horror tale about meat-eating and possession. It’s a Good Life, about a child with godlike powers, sets up a scenario that I still regularly think about. And Vonnegut’s Harrison Bergeron is, of course, a layered classic, rife with mischief.

Outside the library, there’s still a bakery selling cheap bread rolls and jam donuts. (It’s a Primark now.) The smell is intoxicating but the stories already have me.

Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. I feel disconnected from the other children on the playground: like I’m missing a magic password that they know and I don’t. There’s no one big thing, but there are lots of little things; an idiom I don’t understand here, a reference I don’t get there. As an adult, I’ll have a name for what this is and why it’s true: third culture kid. But as a child, I just know that something is off.

The Dark is Rising sequence soft launches as a Blyton-esque adventure in Cornwall, and then dives into a story that is deeper than any of the culture I see around me. In its tales of pagan magic that pre-date the prevailing Christianity, of green witches and Cornish folk legends, it both captivates me and informs me about the history of the place I find myself in. And then there’s Will, and the Old Ones, and a wisdom that cuts underneath the superficial nonsense that I don’t understand and suggests that something deeper is far more important.

When the Dark comes rising six shall turn it back; Three from the circle, three from the track; Wood, bronze, iron; Water, fire, stone; Five will return and one go alone. I can still recite it. The Dark is still rising. There is still silver on the tree.

Ten. There’s a doorway in St Mary’s Passage, a side street in the collegic part of Oxford, that is adorned with two fawns and a lion. Down the road, a Victorian lamppost still burns, albeit with electric light. There are plenty of tourist websites and videos that explain this was the inspiration for Narnia. I mean, it makes sense. But I don’t think it’s true.

Oxford is full of portals. I would know: I was a child there. There are space ships, time machines, great wooden galleons, castles hidden in dimensions somewhere between our reality and another. CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien were both inspired by Shotover, an area of hilly, wooded parkland on the edge of the city. Lewis had a house adjoining the area; Tolkien lived nearby. (Years earlier, Lewis Carroll roamed the hills, too. Years later, so did I.) They’re not the same place, but rather, multiple places that exist as layers over the same ground; different angles and reflections of the same ideas. They were both Inklings, after all.

Anyway, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe tells the truth about portals. They’re everywhere. I still check every wardrobe; don’t you?

Eleven. Twelve. Thirteen. I consume The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, and Life, the Universe and Everything in successive bouts of the flu in our house on the Marston Road, a tiny, water-damaged duplex that my parents have been restoring by hand. My bed is a single red and white bunk above a writing desk, on which I’ve doodled in ballpoint pen.

At the same time, I’ve been playing the Infocom text adventure adaptation, which Douglas Adams was directly involved in. All of these tales are irreverent in a way that directly appeals to me: they poke fun at norms and the bureaucracy of stasis. The books and the game all gently break the rules of their respective forms. They see how ridiculous the world is. This is a different kind of portal: not one to a fantasy realm, but one to a realization that you’re not alone. There are people on the road ahead of you, unpicking the rigidity of the world, and they’re looking back and winking.

And all of us are subject to forces bigger than us. Adams hated the little green planet that adorns every American book and game in the series, but he couldn’t do anything about it. Irony and sarcasm aren’t just forms of wit; they’re escape hatches. At their best, they’re a way of punching up. People who say they’re the lowest are missing the point and are probably Vogons.

Fourteen. It’s not that I’m sick a lot, but grade school is like a Petri dish for colds and flus, so I’m not notsick a lot, either. I’ve finished Douglas Adams but find myself hungry for more, and can’t stomach the direct parody of less wryly satirical books. Terry Pratchett fits the bill, and Mort, the story of Death’s apprentice, is my jumping-off point.

They both eat systems and norms for breakfast, but Pratchett is often more directly, pointedly satirical than Adams was; this is overt social criticism, making fun of people with power and the structures established to dance around them. Teenage me, stuck in my bunk with yet another flu while rain pounds my bedroom windows, literally an outsider while the impenetrable politics and in-groups of high school carry on without me, adores it. I start to see the power of being an outsider. The thing about being a fish out of water is that you can see the water.

It's not worth doing something unless someone, somewhere, would much rather you weren't doing it, Pratchett writes. Right on.

Fifteen. I’m thirteen and sitting in my homeroom class. We’ve all been reading our own books, and our homeroom teacher (who also happens to be our English teacher) has asked us each to read a passage out loud to the cloud. Some of my classmates are reading The Hardy Boys; some are reading Jane Austen; some are reading Tolkien.

I read a passage of Timewyrm: Exodus where the Doctor and Ace are escaping the regenerated War Chief, the villain of 1969 Doctor Who story The War Games, who has helped Hitler raise an army of Nazi zombies. The passage ends when the zombie horde is halted with explosive grenades.

A few kids who generally don’t like to read come up afterwards to ask where I got the book. They seem excited. They seem excited to talk to me. These are not people who usually want to. Maybe I just have to give them something they like.

Sixteen. I catch my reflection in a department store mirror and shudder. Is that really me? Does that really have to be me? How can I stop it?

I look around at the other kids here: slim, elegant, comfortable in their skin. Effortless. Why can’t I be them?

Being an outsider is still being an outsider. By my late teens, I feel like there’s something truly wrong with me: it’s still like there’s a secret password that everybody knows but me, but now the stakes are higher. I want to belong; I want to feel like I have intrinsic value; I can’t find or justify it.

I’m tall now, really tall, and not exactly obese, but not slim, either. More than one person I have a crush on tells me to lose weight. More than one person I have a crush on tells me that maybe I’d have a chance if we had more money or if I wasn’t so weird. I’m constantly exhausted and the wry humor that used to characterize my otherness has been replaced with despair: nothing I do matters because there’s something wrong with me. It’s a firm depression, but either nobody catches it or nobody knows what to do with it. My grades nosedive.

Prozac Nation doesn’t catch everything, but it gives me a window into someone who feels a bit like I do. (I can’t relate to the drugs, but I see the allure, too.) Its author, Elizabeth Wurtzel, is like a cool depressed person: someone who feels this way but is also interesting, desirable, a little bit rockstar-like.

Today, I see the ego. As a teenager, I just see the reflection.

Seventeen. I’ve been writing software for a while now. My mother taught me BASIC on our 8-bit computer when I was five; when I was thirteen, my parents gifted me the PC-compatible version of Prospero Pascal for my birthday. I’ve worked through the manual and written a few small games. My first Pascal effort was Mr A Goes For a Walk, where a letter “A” did exactly that. A year later, I’d written a fully featured Sokobanclone. I’m inspired by Jeff Minter’s seminal (and utterly irreverent) Llamatron and want to build with the same sensibility. Making things feels really good; seeing people enjoy things I made feels even better, and goes some way towards filling the black hole of self-doubt that still lives within me.

Someone recommends Microserfs: a book which should be a warning but isn’t received as one at all. The characters here are quirky outsiders — like me! — who throw themselves into building something on their own terms. They eat flat foods that can be pushed under doors so they can keep working. They struggle with their code, their work, and their lives. And they show me that there might be a place for me.

So many Douglas Coupland books, including this one, are about the emptiness of living in late-nineties capitalism. The clue is in the word serfs, but that isn’t what hits for me. That isn’t what hits at all.

I sit in the sixth form common room, a lounge in my high school where older students can study and do homework, and devour it, as Oasis, jungle music, and mid-nineties hip hop play around me. From somewhere, there’s the smell of cheese and onion crisps. Do they qualify as flat food?

Eighteen. The common room is a harsh place, but just one of a series of harsh places that school has represented for me. Because I’m big and don’t fight back, people feel like they can verbally abuse me, hit me, kick me. It comes from nowhere, usually, and I’m left reeling. Nobody, least of all the people who run the school, seems to want to help. Even today, I see fond reminiscences of people in our school year’s Facebook group, and I think, no, that person caused me so much pain. I’m other to them — a not-person — and that makes me fair game. I’ve internalized that it’s my fault. It happens because I deserve it, and I wonder how I might change to be more acceptable.

I find some kinship in Cat’s Eye, Margaret Atwood’s story of an artist who revisits her childhood home. There’s something in there about the protagonist being untethered from her environment and the cultureof her environment that resonates. The book diverges so far from my experiences after that, but there’s so much here about the act of creation and how it interrelates with identity.

Nineteen. I’m seven years old and at my friend Clare’s house: a typically Oxford Victorian brick home that spreads over multiple floors. Her dad, Humphrey, has an office off of the stairs that I’ve only seen a glimpse of: there’s a desk with a typewriter and while he’s a very kind man in my eyes, he absolutely does not want us to go in there. He writes for a living, which seems like a magical thing to be able to do: the way I see it, you get to tell stories all day long. You get to create.

Later, he asks me what I want for my birthday, and I’m too shy to tell him what I really want, so I say a My Little Pony. What I really want is for him to sign Mr Majeika for me: a story that’s fun in itself but clearly anchored in his life, his family, his personality. I still regret being shy about that.

Twenty. Years later I find Humphrey’s official biography of JRR Tolkien at Moe’s, a chaotic used bookstore in Berkeley, and buy it immediately. I’m not particularly interested in Tolkien but I remember Humphrey fondly. It’s a portal to him; to that time; to a feeling of possibilities; to laughing while running up the stairs.

Twenty-one. TVGoHome, by an online writer I like called Charlie Brooker, is exactly what I like: a spoof of mainstream culture, through parody TV listings, that doesn’t hold back. One of the fake shows from the listings is later turned into a real show. Later, the author makes a spiritual follow-on about a zombie outbreak on the set of Big Brother. It’s a natural progression but I’m amazed they let him do it.

His final form is Black Mirror, which starts with the Prime Minister and a pig and winds up in sweeping cinematic dystopias starting Mackenzie Davis, Miley Cyrus, Bryce Dallas Howard. It all starting with comic strips advertising a dusty old second-hand store in inner London, and it ended somewhere so much grander, so much more global, without compromising almost anything. The claws are intact.

The book inspires me; the rest of it, too, but later. I wonder if I can be this kind of creator too; a curator of portals for other people to step through, to take them out of the water so they can see it for what it is. Or, at least, take a swipe at the places I can’t seem to fit.

Twenty-two. I wanted a clean break, away from Oxford and the trap of who I am, but this isn’t what I was going for.

I’m in a block of student flats in Edinburgh. If a door shuts anywhere in the building, you can hear it anywhere else: the sound carries, and people are drunk late into the night, and there’s never any peace. A fierce winter wind blows at the windowpanes. The mattress is covered in shiny plastic and I can feel it through my sheets.

I’m fascinated by Brave New World and its setup of totalitarianism defended by acquiescence: a world where nobody has to ban books because nobody wants to read them. A dystopia protected by distraction. From my vantage point, it seems plausible.

Sometimes, my flatmates barge into my bedroom and pile onto me. One likes to spit in my food as I’m cooking it. One inhabitant of the building tells me not to talk to him. It doesn’t feel very far away from my high school common room, as much as I wanted it to be.

Twenty-three. I’ve decided to study computer science, but immediately realized my mistake. It’s not the study of how to make tools for people that empower them in ways they weren’t before; nor is it the study of how to tell stories with new means. It’s a practice rooted in mathematics and physics, of the underlying mechanics torn from the underlying humanity that gives any of it meaning. I hate it. I truly hate it.

And yet, although every day is a slog, I decide to stick it out. I know I’ll be able to use it later on.

The British system is very far from the American liberal arts approach of allowing students to choose their major after sampling a range of subjects. Here, you effectively have to choose your major when you’re sixteen, and it’s very hard to change. There is very little opportunity to study outside of your core subject.

But I do have one elective, in my second year. I choose Forensic Medicine because I think it will be useful fuel to tell stories. I learn about how forensic pathologists use blood spatter to determine the direction of blows and what kind of weapon is used. I learn Locard’s Principle of Exchange, which dictates that every contact leaves a trace: something that seems to apply far beyond the subject. Every time you touch something, every time something touches you, a trace is left. Inspired by this principle, I decide not to attend the optional autopsy lecture, fearing that it will change me in ways I might not like.

Simpson’s Forensic Medicine is a grisly book, but at least it’s not advanced calculus.

Twenty-four. Twenty-five. I came to Edinburgh because it was a cultural center more than because the university had a good computer science program, although both things are true.

I’m in a tent at the Edinburgh Book Festival, chatting with Garry Trudeau. I’ve loved his comic strip, Doonesbury, since I was an early teen; I started with his late-seventies collection As the Kid Goes For Broke, which was lying around my great grandparents’ house, and kept reading. It’s got its claws into the world in the way I like, but somehow made its way into the mainstream, normy Sunday comics section.

He’s a delight. We’re talking about Asterix the Gaul, a comic it turns out we both love. I can’t believe my luck.

How can I be one of these people?

Twenty-six. I’m on the streets of Glasgow, protesting the impending war in Iraq. Altogether, two million people in the UK — around 3% of its entire population — are protesting with us. Some have pre-made placards made by the usual organizations that want to spread their own agenda as well as the matter at hand; others have homemade signs. My friend carries one that simply reads, “too angry for a slogan”.

It’s clear that the war is based on bad information. The so-called “dodgy dossier” of information about “weapons of mass destruction” is so obviously fake long before it is officially revealed to be. And yet, Britain is part of the invasion, and the dossier of convenient unfacts is used to help justify George W Bush’s war effort.

I’m new to politics and I’m apoplectically angry. Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent has some of the answers I’m looking for. I don’t like the implications, but the arguments resonate.

Clawing at the status quo mainstream starts to mean something more than poking fun at the ridiculous nature of class and power imbalances. Sometimes, lives are on the line.

Twenty-seven. Twenty-eight. I’ve graduated. Almost immediately, I go back to work for my university; at that time there aren’t very many software jobs in Edinburgh, and I’ve grown into the city to the extent that I don’t want to leave quite yet.

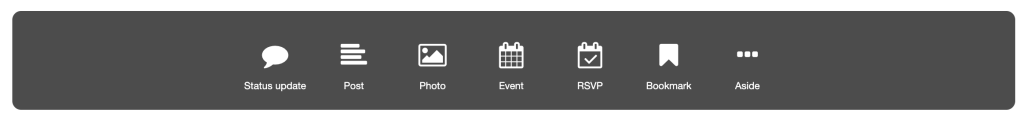

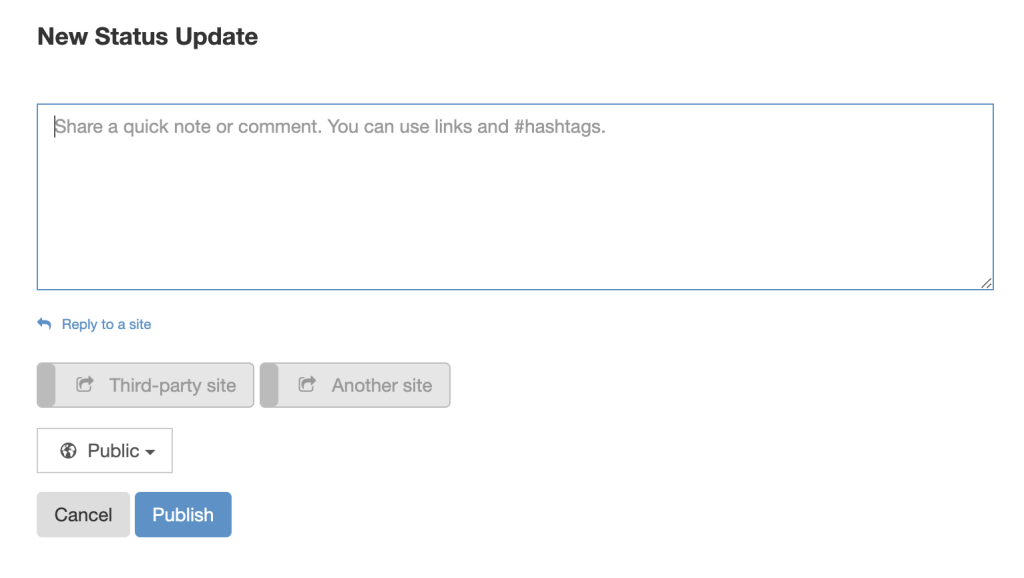

I find myself working out of an office — actually a converted broom closet with a window that doesn’t shut, directly above where they fry the chips for the study canteen — at the Moray House School of Education with a belligerent PhD candidate who resents my presence. By necessity, we start talking, and it becomes clear that we have something to share with each other. He’s knee deep in the educational technology world, where people are starting to talk about “e-portfolios”: a collection of examples of academic work that sound a lot like social media if you squint a bit. In turn, I’m a programmer, a writer, and a blogger.

We build a platform together. I call it Elgg, after the town in Switzerland the Werdmullers come from. It’s inspired by Brad Fitzpatrick’s LiveJournal but is designed to be as easy to install as WordPress. Some people seem to like it.

My first published work is a co-written chapter in The Handbook of Research in ePortfolios about our work. Later, people write full-blown books about our platform.

I move back to Oxford so that I’m closer to the London software ecosystem. We rent an office above a bookstore in Summertown, down the road from a Lebanese deli and a wine bar that for some reason sells excellent croissants. Some days I’m too excited to sit still in my chair.

I’ve (co-)created something that people like, and found a community in the process. I feel prouder and happier than I have since I was a child. I feel like this was a portal worth falling through.

Twenty-nine. Ben Brown seems interesting. I’m introduced to his site Uber through an Edinburgh friend: irreverent writing with an internet sensibility. I’m heavily online at this point — blogging, but in ways that feel uncool and awkward. What Ben is doing is very different; literary in a way. It’s a precursor of publisher like The Toast and even McSweeney’s.

Ben publishes books as So New Media, an indie house co-founded with James Stegall. I buy Beneath The Axis Of Evil: One Man's Journey Into The Horrors Of War by Neal Pollack. Yet another dive into the Iraq War; another clawback at the Bush / Blair continuum.

Ben’s whole enterprise is inspiring: you can go it alone now. You can maintain your voice. And you can still find an audience while leaving yourself unmoderated. In some ways, on the internet, the rougher your edges are, the easier it is for other people to latch on to you.

Years later, I meet Ben in person at XOXO (he silently sidles up to me at an X-Men arcade machine). Years after that, I buy him lunch in San Francisco. I don’t think he knows exactly what it means to me.

Thirty. Thirty-one. Thirty-two. I’m exhausted; gaining weight; my feet, for some reason, are constantly cramping up. It’s all stress. All the startup.

My partner is constantly telling me that I need to relax and take time away from work. The startup is all-encompassing; stressful; in every part of my life. My friends and family try to ban me from working past 7:30pm. She buys me my first-ever massage, which is a revelation, and suggests books for me to read.

I’d previously read Maus, a graphic novel that is both autobiographical a vividly-painted portrait of the horrors of the Holocaust. It uses the visual language of comic strips but the meaning runs deep. I come from a family that was also thrust into WWII: my father is a Japanese concentration camp survivor, my (Jewish) grandfather on my mother’s side was captured by the Nazis and presumed dead. The story itself resonates with me, but the form does too: comics are a flippant visual medium, in a way, but here that’s used as an entry point for a realism that might not have hit as hard another way.

So Helen introduces me to Alan Moore: first through From Hell and then V for Vendetta. Unlike Maus, these are unapologetically fiction, but the use of the comics medium is similarly effective. I particularly like the way From Hell establishes a new psychogeography of London, rooting the story of Jack the Ripper in its location by adding layers and resonances that tie back to the planning of the city itself. It adds something new to places I’ve walked all my life. That’s good. I’m looking for something new.

Thirty-three. My co-founder likes to tell new people we meet that we’re not friends. More than once, he’s threatened to physically fight me: most memorably over the limitations of the OpenID specification. On a drive through the rolling Yorkshire hills, sunshine dappling the moor grass, he tells me that he’s worried about hiring women because they might get pregnant. He pulls me aside during a contract for MIT to let me know he’s in this for himself and that I should expect him to make decisions with that in mind. On a work excursion to Brighton, he refuses to eat with the rest of the team.

This is, in short, not working out.

The business threatens to move towards servicing hedge funds, and I choose to leave. One afternoon, I simply close my laptop and listen to the quiet of my house, the footsteps of pedestrians on the street outside, the swoosh of passing cars. Later, there will be worries about money and what exactly I will do next, but for that one spring afternoon, I feel weightless.

I need punctuation. A clean break.

I’ve never been to Rome in living memory. As it turns out, it’s also cheap to get there.

My then-partner and I spend ten days roaming its ancient streets, armed with the Rough Guide to Rome. “I don’t want this to end,” she says, as we eat grilled artichokes and cacio e pepe on outdoor tables set in a cobblestoned alleyway. It’s a new relationship and we’re discovering each other as well as the twists and turns of an ancient city. “Me either,” I say, and I take another bite.

Thirty-four. I’m six years old. My grandparents live with us for a little while in a grand old house in Oxford: a stone Victorian with a curved driveway and a big back garden. The kitchen has terracotta tiles. My Grandma reads The Black Island to me in my bed and stays with me for a bit while I drift off to sleep.

I’m seven years old. I’m told to stay in my bedroom. My mother’s received a phone call and is crying in the living room. I’m not to go see her. I’m to wait. My Grandma had pulmonary fibrosis in her lungs; she was finding it harder and harder to breathe. And now, so suddenly, she’s gone. All the way in Texas; thousands of miles away from my mother. I can’t begin comprehend the loss but I know that if my mother was sick I would want to see her again.

Thirty-five. My parents have lived in California for years now: first to look after my Oma, and then just to live. Ma — after consistently calling her by her first name throughout my childhood, she’s Ma to me in my thirties — has retrained from an analyst for the telecommunications industry to a middle school science teacher in one of the central valley’s most impoverished districts. She loves her work in a way she never did before.

But she has a persistent cough that won’t let go.

At first we wonder if it’s just the dust of the Central Valley: almond shells and the detritus from overfarming. Maybe she just needs clean air.

It’s almost Christmas-time. I’ve wrapped a copy of You Can Write Children’s Books. She would be so good at it — her writing, the way she tells stories, has always been so magical to me — and it’s so in line with what she’s turned her life to do.

In the liner, I add some written lines of my own, based on her life in Oxford:

In a house at the bottom of a hill, in a small town that rarely saw the sun, there lived a little dog who loved to play.

A few days before Christmas, we understand that she has pulmonary fibrosis. This same thief of a disease my Grandma had. We knew, in a way — my dad, in particular, knew — but the diagnosis makes it official. It’s a new cloud.

What we don’t understand:

What happens next.

What to do next.

How long she has.

Who else will get it.

Why.

Thirty-six. My sister is reading my copy of Parable of the Sower to Ma. She’s perched on my parents’ bed in Santa Rosa. Outside, the sun is shining over the Sonoma hills. Somewhere, my dad is tinkering with something downstairs.

It’s been a while. My sister and I both moved to California, starting from scratch. Ma continued teaching for as long as she could; her middle school science teachers were fascinated by the oxygen tanks she began to wear on her back like a Ghostbuster. Then it became too hard and too heavy, her oxygen needs too great. I sent a Hail Mary letter to the hospital explaining how badly in need she was; her oxygen concentrators were refrigerator sized and running in parallel, her movements limited by how far her cannula tube could extend. Eventually, at the very last moment, they tried something new and cut a set of lungs down to fit her size in order to try and save her life.

The first night, I refuse to leave her side. The doctors eventually kick me out of her ICU room and I sleep in the family room down the hall. The day after happens to be the Super Bowl; she takes her first post-double-lung-transplant walk just as Beyoncé takes to the halftime stage to sing Crazy Right Now.

Now, a few years later, the drugs are taking their toll. She’s tired. She’s often ill. But she’s here. My sister likes to read to her, and she loves lying there and listening. Other times, at the dialysis she now needs because the anti-rejection drugs have killed her kidneys, she reads on a Kindle with the font size cranked practically as high as it will go.

Every day is a gift. Every contact leaves a trace. Every book is a portal out of here.

Thirty-seven. The last book Ma and I read together is The Nickel Boys. It’s the kind of thing she likes to read: a story about America’s monstrous history, told with skill and resonance. We share our reflections of it; the experience of reading the same ideas. Asynchronously, sure, but together all the same.

Thirty-eight. When I move to California I land in Berkeley. I find myself a coworking space above a coffee shop: a mix of developers, academics, and artists. Most of us have a standard office desk, but one inhabitant, Hallie Bateman, has brought in an antique wooden artist’s desk that looks like it’s been dropped in from another dimension. It’s covered in paintbrushes, inks, and paper: fragments of a very different kind of professional life to the one I’m leading.

I continue to follow her work long after we share an office. When she publishes What to Do When I'm Gone: A Mother's Wisdom to Her Daughter — instructions from her own mother about what to do once she dies — I buy it immediately. Back then, when Ma was still around, I could read it all the way through. I no longer can. It sits on my shelf and I sometimes think about it, but grief is like a wave, and I know it can overtake me.

Instead of asking Ma for instructions, I sit down with a tripod and a camera and I record her life story, instead.

Thirty-nine. My Aunt publishes a book about evaluating scientific evidence in the context of civil and criminal legal contexts.

I have it, of course, even though I am not a lawyer and I have no professional need for it. I remember her poring over the edit on her laptop in the downstairs bedroom in my great grandparents’ house on Cape Cod.

The last time I see her, we eat Thai food in the Tenderloin. I have no idea it’s the last time. This disease is evil.

Forty. Forty-one. Forty-two. I’m in Santa Rosa and can still hear the wheels of the pole the feeding tube hangs from wheeling across the floor; of the oxygen clicking through the cannula; of my parents talking. It will fade, eventually, but I’m haunted now, and lost.

My mother talked about being radicalized. Both my parents were Berkeley radicals, which just means that they took action on causes they cared about. I think about all those people I’ve looked up to who kept their claws sharp, who dug in, who fought for equity and didn’t compromise their values, who had a voice and used it.

I walk the Santa Rosa hills, looking at these big houses on the edge of wine country, and listen to the audiobook of The Jakarta Method, which details the murder undertaken in the name of America. I re-read The Handmaid’s Tale. Through Caste, I’m appalled to learn that Hitler’s treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany was inspired by American Jim Crow laws.

By now I know that I won’t get the disease — or at least, not according to our current understanding of that. It’s a genetic mutation that I don’t have. But regardless, we all have limited time, and none of us know how much time we have left. Time is ticking for everyone.

I think about how I might do a better job of using my voice to make the world better. Later, I’ll start applying to jobs where I can help people speak truth to power; to work to further the work of journalism. To honor my mother — really to honor both my parents — and what she stood for in the world. I want to live up to them.

Forty-three. I allow myself to start to write again. Words, not software. It feels daunting. My cousin Sarah, who is a very successful author (and whose books, although not designed for me, have made me cry), once recommended Bird By Bird. I’ve come back to it again and again: it’s about writing but also not. Its lessons are relevant to anyone who is building something big and new; anyone who is picking themselves up.

You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories.

Forty-four. The last book Ma gives me is Between the World and Me: a letter from Ta-Nehisi Coates to his son. It is masterful. A portal to lived experiences I don’t have; a way in to understanding them, and through this understanding, to better understand the role I have to play, too.

It’s not the main point of the book, but one of those unknown lived experiences: having a son and the sense of responsibility that follows. I can’t imagine the fear of caring for a child while being Black in America; I can’t imagine having a child at all.

Forty-five. Erin’s labor has been two days long, difficult, and painful. Our son wasn’t breathing in the way they expected him to, so I’m standing at a table off to the side while they put a mask to him and try to get him to start. I find myself wondering if this is, somehow, the disease, this curse, out to get us again.

Eventually, after a few minutes that seem like days or years, my heart pounding in my chest all the while, he breathes normally. We’re able to return him, the doctors and me, to his waiting mother. He cries, then snuggles in. She cries with him.

I can’t believe Ma will never meet him. She’s there, of course. I remember the songs she sang to me and sing them to him; I find myself using the same words to console him and to let him know he’s loved. Maybe I won’t read him The Hundred and One Dalmatians, but I have other books in mind.

There will be new books, too, that we did not discover together but will continue our story.

Have you ever read The Runaway Bunny?

“If you become a bird and fly away from me,” said his mother, “I will be a tree that you come home to.”

She is nowhere and she is everywhere. I see her in him. I see myself in him and him in me. Every contact leaves a trace. We are a continuum.

Forty-six. Donald Trump has been re-elected. The shadow of renewed nationalism, of division, of hate feels heavier than ever. The world is at, or on the brink of, war. I remember marching in Glasgow, the despair when it came to nothing. We are all in need of a refuge. We are all in need of portals out of here.

We’re lying in bed: Erin, him, and me. “Read a book?” My son asks me. Of course I read to him. Of course.

I open The Story of Ferdinand and begin:

Once upon a time in Spain there was a little bull and his name was Ferdinand. All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand. He liked to sit just quietly and smell the flowers.

He snuggles into my arm and I stay with him until he falls asleep.

Share this post

Share this post