Dear Ma,

My child was born last Friday. I wish you could meet them.

The first time I saw their face in person (strikingly similar to their 3D ultrasound, but here, not an echo of a person but a real-life human being in front of me), they couldn’t breathe. The doctors whisked them away to a table, and I followed quickly, dumbly, the delirium from sleeplessness and from the surrealism of it all instantly snapping into pure, adrenaline-fueled presence. They put a mask on their face and applied pressure to their lungs, asking each other why they weren’t crying. Finally, there was a sound, like a tiny grunt. And then a little sigh. Finally, they opened up into a small cry; then, another, louder one. The smallest little human I’ve ever seen, finally arrived. I fell in love immediately.

The last time I saw you, just over a year ago, you were in a bed in the same institution, your donated lungs breathing fainter and fainter. I kissed you on the forehead and told you I loved you. You’d told me that what you wanted to hear was us talking amongst ourselves; to know that we’d continue without you. In the end, that’s what happened. But I miss you terribly: I feel the grief of losing you every day, and never more than when my child was born.

They’re so incredibly cute. I just want you to see.

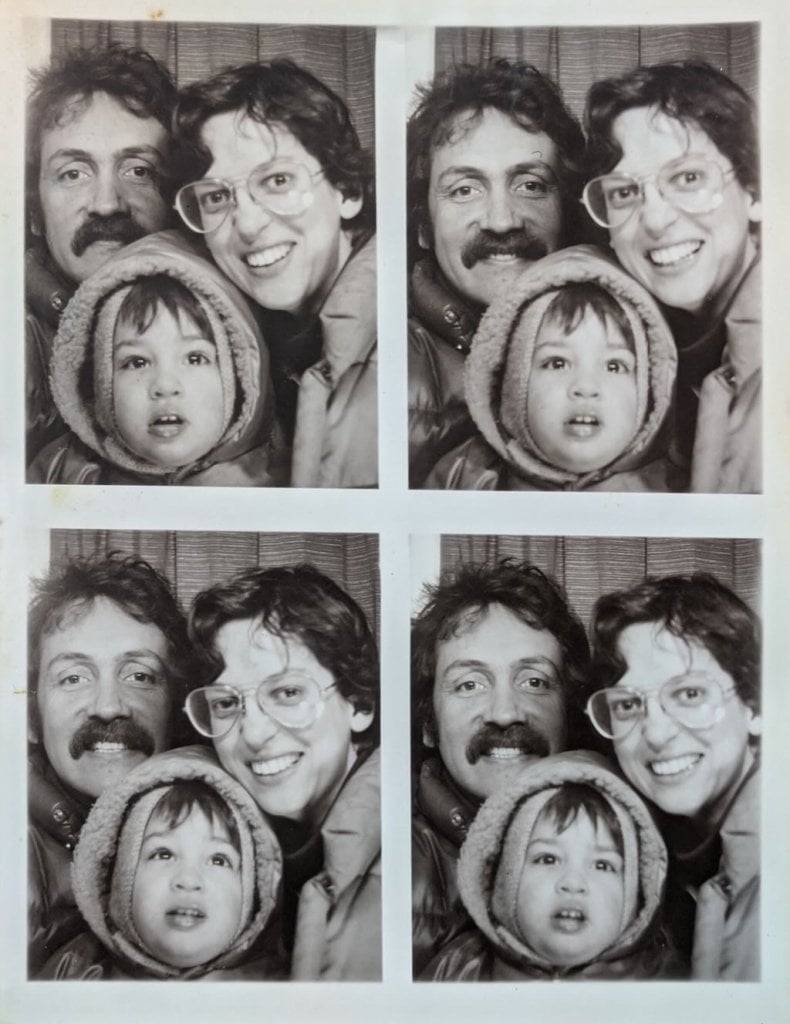

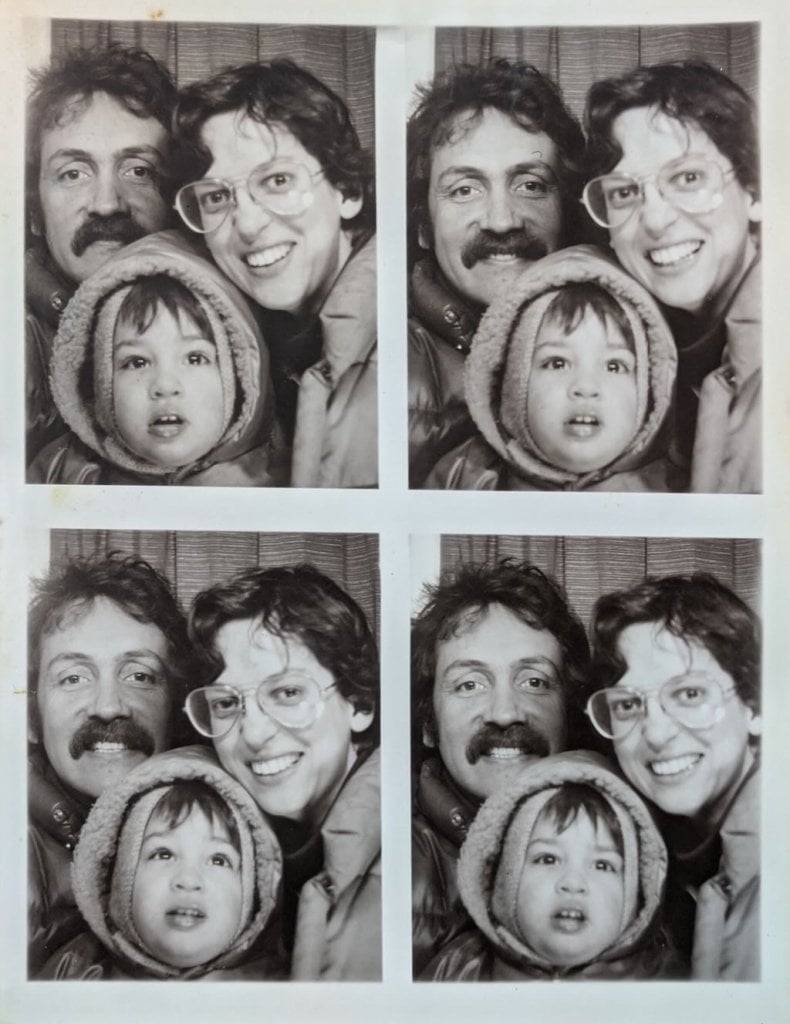

I’ve been thinking about the cassette tape recording we have of when I was born. “It’s a baby!” you exclaimed, and we’ve always thought it was funny, because what else would it be? But I now understand that the enormity of that moment is stunning: a potential human made up of ideas and imagination, that we can only guess about, turns into a real-life human being. It’s a baby. Holy shit. Everything suddenly changes. Everything.

(I want to digitize that recording. Tapes degrade. It might even be gone already.)

You were always so good with children. Famously so. Babies loved you; children loved you. Every photo I have of you with a child is of you looking delightedly at each other, fully present in a joyful interaction. When you did your career about-face and became a schoolteacher, it was the most natural thing in the world, because it just made official what you’d always done. Of course, I saw the benefit of that care and love, too. I wish they were able to feel it directly. As it is, in this worse universe that doesn’t have you in it, I’ve been intentionally trying to channel you. I’ve been trying to imagine how you would have shown up with them, and what your advice for me would have been. I’ve been trying to convey that good-humored warmth I always felt. You made me feel safe: physically, yes, but more than that, emotionally. I want to make them feel safe, too: to be who they really are.

They have the privilege of a tightly-knit family. I can’t wait to introduce them to my dad, and to my sister, who are the best people I know. I want them to be deeply involved in their life. You will be too, through us, but I wish it could be through a hug or smiles or belly-kisses.

I guarantee you would have loved them. I guarantee they would have loved you.

Erin’s quickly turned into such a good mother, Ma. She really is; you’d love it. She’s so attentive, and smart, and worried about them, and prepared in all kinds of ways that I would never think to be. So far, we’ve made a pretty good parenting team. There’s so much to learn, so much to get better at, so much to worry about. But she’s good. It’s fun to think of them having fond memories of her in the same way I have fond memories of you.

It’s also weird to think of them thinking fondly of me in the same way I love my dad. Those bonds are strong. I have trouble thinking about anyone loving me deeply, but I know I love deeply, and my dad is one of the people I love the most, so the possibility is there. I hope I can live up to that for them. It’s scary to think about.

I remember, very early on, going on a protest march with you. As a child, I inherited your buttons and proudly wore messages to ban the bomb and embrace renewable energy. (Those slogans seem like ancient history now, but also still so relevant.) Progressive values and the value of protest were normalized for me. Living in Oxford, we were surrounded by university, and you were both life-long students, so I was raised in an environment of debate and deep thought. Because I had parents who talked about the world, both around me and to me, I had a better sense of my place in it. I want that for them, too.

We seem to be backsliding into a world where nationalism is a respected value, and where fierce individualism trumps all, even as we plunge deeper into a climate crisis whose only real solution is for us all to work together. We have to think globally, as one people, and we have to care for people on the other side of the globe as if they were our neighbor. We have to call out our own governments when they oppress others, at home or abroad, and we have to be forces for equitable, inclusive, collaborative kindness in a world that is dominated by competition and profit. We seem to have forgotten the importance of community, and of acting collectively - or, worse, rejected it, as if being an actively participative part of a fabric of interconnected souls somehow impedes our individuality. On the contrary, I think it uplifts us. In a world where we all have a duty of care for each other, we can more truly be ourselves.

I got that from you.

I wish those ideas were a given, but they’re going to have to fight for it. We’re constantly re-litigating the same arguments about religion, bodily autonomy, the climate, when we could be building on what we’ve learned to climb ever higher. Their world will have fewer resources, constrained by a heating planet. If it also continues to have widening inequality and an addiction to wealth hoarding, it will also have more conflict. It will be a worse place to live: more dangerous, more authoritarian, more brutal. “Building a better world for our children” is no longer an abstract sentiment for me, and my fear is that they will have this realization one day too: they may find himself wondering how to show up to make a safer, kinder world for their child.

We need to make more progress.

You described yourself as having been radicalized. That word means so many things: to me, your values were never radical. They were simply common sense. We need to take care of each other; we need to love our neighbors, and understand that everyone is our neighbor; we need to undo systems of oppression and inequality. You worked for affirmative action and stood up in court to establish and protect the rights of tenants over landlords. You marched and donated to causes and let your worldview be known. You were a force of light in the universe, not just for how you acted towards everyone who knew you, but how you showed up in the context of wider systems. If you were radicalized, I guess I hope I am too.

You had no time for people who didn’t care about others: hardcore conservatives, neo-reactionaries, libertarians, and fascists. You cared about fairness and inequality. You were an ardent feminist. You were an anticapitalist. You believed in true representative democracy. You continued to learn and evolve your understanding of systems of oppression. I love all of those things about you - just a fraction of all the things I love about you. I want to model that way of thinking and acting for my child.

I want them to have broad horizons, and to understand that all of this - everything - can be changed for the better. Change is inevitable; how we change is up for grabs.

You were always so flexible: so up for the adventure. You traveled thousands of miles to have me in Europe. By the time I was three years old, I’d lived in four cities. As time goes by, I’m more and more impressed by your ability and willingness to just up and leave and try something new. My life has been much better off for it. I think your life was much better off for it.

Remember living in Oxford? You had that upstairs office above Daily Information, where you’d work on predictions for the telecoms industry - you predicted the rise of cellphones, home internet, ubiquitous broadband - while our Jack Russell terrier, Tessie, would patiently sit in her bed. At noon precisely, she would walk over to you to let you know it was time to take a break, and you’d take her on a walk to Port Meadow. Both you and my dad took classes when you wanted to, often just to improve your knowledge for its own sake; you didn’t have to worry about return on investment, or healthcare or education costs for your family. It all just worked, so simply. I miss that lifestyle. I miss the peace of it all: the lack of fear that comes from real support.

So I’m now faced with a similar question to the one you must have been considering. The US is such a big country, and it contains so much, but it’s also so isolated, and by extension, so isolationist. Save for tribal nations, you can drive for thousands of miles without hitting another country. It would be easy to grow up here and have a very insular worldview: look at all the people who swear blind that “America is the best country on earth” but have never lived or spent much time anywhere else, and who consider blind patriotism to be a virtue rather than the cult-like ignorance it is.

When we build software, we learn that the settings we choose to be the defaults are incredibly impactful: those defaults permanently affect how someone will use the product you’ve made. It seems to me that this is even more true in life. Regardless of the choices they make later in life, the defaults I give my child will permanently affect their worldview. By traveling around and seeing the way different people live, not on a tour bus but immersively over time, we learn that there are lots of valid alternatives; we meet and get to know lots of ways of being, and understand that ours is not better than theirs. If we don’t, I’m worried that the way the community around us lives becomes the default, and that the rest of the world becomes a little scary. My child has multiple passports to draw on; they will have the ability to live in, or at least visit, so many places. It would be such a missed opportunity to not give them that perspective. The more easily we can all relate to people from different nations, the easier it will be to have a globally-minded, kinder world.

Make no mistake: I know you would want me to make sure they see alternatives to living like we do here, and I will make sure that I do. So much is wrong. Every school shooting is shocking, but the safety drills they make children do are almost as terrifying; the ideas that are traded as normal are so brutal. Violence is ingrained everywhere. What kind of country watches little bodies be slaughtered and refuses to take any kind of meaningful action? We still kill prisoners. The police commit murder. And we call this civilization? I don’t want my child to grow up thinking any of this is normal. They need to see that it’s a uniquely American problem by spending a lot of time outside of America.

But for all they can learn from it, international travel itself has a climate impact that is worsening the conditions that will make life harder for them over the coming decades. I don’t know how to reconcile that: I don’t think the world is better if people don’t travel. You often told stories of the times you lived in Italy, or Israel, or the UK before I was born. Your parents visited countries all over the world and often took you with them. We traveled often around Europe in particular. Maybe it’s because I inherited that background, or because our own relocations made my sense of place less tethered, but I think the ability to see the world face-to-face should be as accessible as possible.

I think you’d have a smart way to think about that, or to look at it from another angle. You might, I think rightly, point out that the bulk of the climate crisis lies in the hands of corporations and industry. That they spend time and dollars on casting the blame elsewhere. But you’d also care and worry about your own contribution: you wanted an electric car before most, you wanted solar, you supported renewable energy and the politicians who supported it.

As I write you this, my child is fast asleep, lying skin-to-skin on his mother. His face is unbothered by any stress or worry. He hardly cries. When he wakes up, I’ll check his nappy, keep him clean, and we’ll feed him. We’ll talk to him, and play with him, and sing and tell him we love him, and let him drift back off into slumber.

There are people in the world who would wish this sweetest human harm. They’re part-Jewish; they’re from more than one place; they are not being raised to believe in a religion; they are going to be raised to be in opposition to wealth hoarders and rent-seekers and nationalists, in a culture of broad, inclusive love. These would-be-objectionable traits are all the products of dead-end mindsets that should have withered away in the 20th century. With a small amount of luck they’ll live to see the first decades of the 22nd century, and I imagine those ideas still be with us then. But I hope they will be fringe by then, and I hope my child has a part to play in their demise. They do not deserve to define what the rest of us do.

I grew up knowing that my father and his family lived through a concentration camp when he was just a toddler; that my maternal grandfather was captured by the Nazis and thought dead; that my great grandfather escaped White Army pogroms in Ukraine. I heard my grandmother screaming through the walls every night as her dreams took her back. Through my family and the ripples trauma leaves across generations, I understand the consequences of hate. And I understand that the definition of “fascist” isn’t predicated on death camps and goose-stepping; it isn’t set in the early 20th century. It’s a mindset rooted in nationalism, tribalism, and the noxious idea that some people are inherently better than others. It’s an idea that did not go away at the close of the Second World War, is not limited to any nation (of course Americans can be fascist), and is so pernicious that my child and their children will both need to be aware of its toxicity, long into the future.

The period we’re living through now may be just the very beginning stages of a world with fewer resources controlled by ever-fewer people, who will use increasingly-authoriarian methods and appeals to existing divisions to try and maintain their holdings at the expense of others. Ma, the only way I can see through this is by living how you did: with kindness, by not holding back our opinions, and by active work to make everything better.

You showed me the way. I’ll try and do my best.

I love you. I miss you. I wish you were here.

Share this post

Share this post