A quick note before we begin: This post reflects my own views on newsroom technology leadership, not necessarily those of my employer.

I like to say that journalism treats technology as something that happens to it — like an asteroid. But technology is too important to the future of news for it to be treated passively.

Journalism’s most impactful publishing surfaces have all migrated to the internet: websites, newsletters, aggregators like Apple News, social media platforms, and streaming media. And most crucially, every publisher lives or dies on the web: it’s the platform where articles are shared and discovered, where a publisher makes their first impressions, and where most of their revenue is earned.

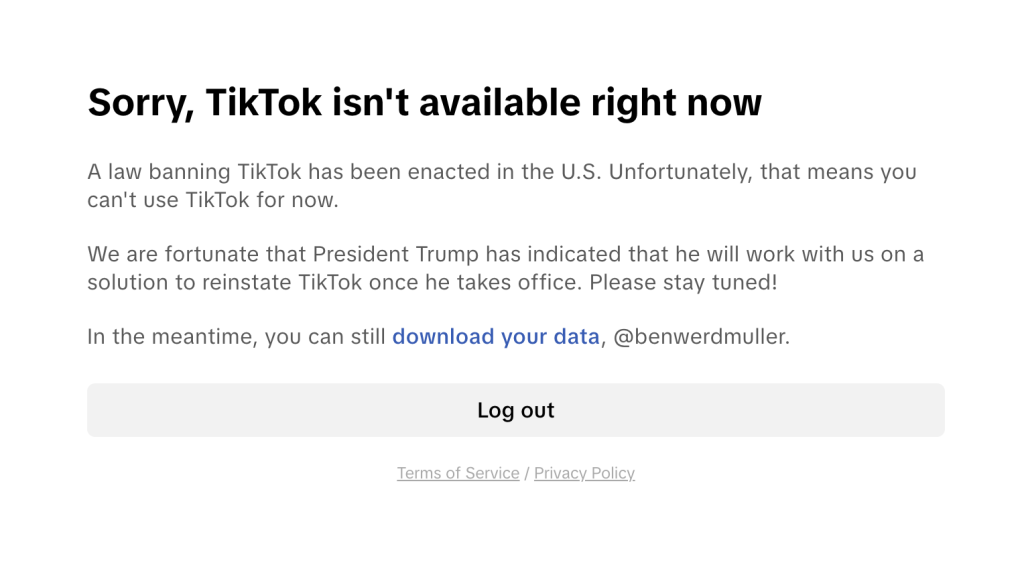

Recently, journalism’s existential threats have also been rooted in technology: radical changes in the social media landscape and referrals from search engines have been ongoing for a while, and AI threatens to shift the way people learn about the world towards black-box proprietary systems that are prone to hallucinations, bias, and misinformation. We’re in a period of great platform change.

I believe journalism is the bedrock of democracy. We need a functioning press in order to speak truth to power and ensure we have an informed electorate. As an industry, it’s in trouble for many reasons — primarily that it’s lost trust with the people it seeks to serve. This is, in part, because it often fails to be truly representative of the interests and demographics of their communities. And, obviously, not every newsroom lives up to its journalistic responsibilities. But it’s also because it often insists on clinging to the norms, traditions, and voices that worked for it in the print era, even as the internet has brought about great cultural change. The way people relate to information and institutions has been radically altered forever.

Building a strong technology competence inside a newsroom is existentially important. Given journalism’s platform dependence, it’s vital to build and shape the technologies that newsrooms rely on in order to function. Given journalism’s cultural dependence, it’s also vital to ensure a newsroom understands how the internet is building and shaping culture — not just at the periphery, but as a core part of its own culture.

In this piece, I’ll explore how I suggest building these technology competences into a newsroom that doesn’t yet have them. It’s partially about building a team, but newsrooms often operate on low budgets; it’s also about establishing a mindset and practices that will help any newsroom adapt to, and plan for, technological change.

Everything big starts small. If you want to spread a technology competence throughout your organization, it all starts with finding a leader you can trust.

Finding a technology leader

The case for a technology voice in senior leadership

Every newsroom has a senior leadership team, whether they call it that or not: the collection of people who set strategy for the organization across its key areas of operation.

This usually includes:

- Editorial: The editorial vision, standards, and content strategy that define the newsroom’s journalism.

- Fundraising / Development / Revenue: The strategies that bring funds into the newsroom and allow it to continue operating.

- Finance: The budgeting and accounting that keeps the lights on and allows the newsroom to plan for the future.

- Operations: Day-to-day management, HR, vendor relationships, office management. More progressive newsrooms elevate People into its own function (as they should).

- Legal: Risk assessment, compliance oversight, and legal protection for the newsroom’s journalism and business operations, including press law, source protection, records requests, and contract review.

More recently, some newsrooms have added:

- Brand / Creative: The visual identity, tone, and creative strategy that shapes how the newsroom presents itself across all touch-points.

- Product: The design, functionality, and user experience of how readers actually consume the newsroom’s journalism. This often also includes partnerships with other newsrooms.

Given my previous discussion about journalism’s existential interdependence with technology, adding technology leadership to this mix is vital.

Product is not Technology

Many newsrooms conflate Product and Technology leadership, but they’re different disciplines. Product leadership focuses on the “what” and “why”: understanding user needs, defining features, prioritizing what gets built, and ensuring the end result serves both readers and business goals. They need to understand reader needs, culture, and expectations.

Technology leadership focuses on the “how” and “what’s possible”: the technical infrastructure, capabilities, and strategic technology decisions that enable everything else. They need to be able to understand the implications of today’s technology for the newsroom, including how technology is shaping how people interact with information, but also predict technological changes and understand the impact of those futures, too.

Both Product and Technology leadership need to have an understanding of each other’s worlds. Product needs to be technologically savvy, but is centered on reader and business needs. Technology needs to have a solid understanding of readers and the business, but is centered on the practice and culture of technology.

This needfully encompasses security and privacy, so technology leadership needs to have a holistic understanding of the impact of technology on people and communities. Because Product encompasses the experience of interacting with the newsroom, product leadership needs to have a working understanding of what’s possible.

It’s also about who has the final word. While many decisions should be made collaboratively, responsibility for the technical underpinnings — particularly when it comes to privacy, security, and infrastructure — must ultimately rest with technology leadership. In turn, responsibility for understanding and meeting reader needs rests with Product. And, of course, in both cases, they need to translate their realms of experience and set standards for the rest of the newsroom.

What to look for in a technology leader

At this point, it should be clear that I don’t think being a great engineer is enough to make someone a great technology leader. A pure engineering leader is typically a Head of Engineering. In contrast, a technology leader is more strategic, more predictive, and more people-centered.

As a field, technology sometimes gets a reputation as a place where hard logic is prized, where empathy and social consciousness are not needed. That attracts exactly the wrong people. Fundamentally, technology leadership is as much about humans as it is about technology itself, and doing it well requires empathetic leaders who understand people well, who in turn will build teams with those same qualities.

When I’m thinking about hiring technology leadership, here’s what I have in mind:

- Strategic technology vision: The ability to see beyond immediate technical needs to understand how emerging technologies will reshape journalism. They should be able to anticipate platform changes, evaluate new tools critically, and help the newsroom adapt proactively rather than reactively.

- Cultural fluency: A deep understanding of how internet culture works: how information spreads, how communities form around content, how trust is built and lost online.

- Newsroom sensitivity: A respect for journalistic values and ability to make technology decisions that support rather than undermine editorial integrity. They must understand when technical efficiency might conflict with editorial principles, and how to navigate those tensions.

- Communication skills: An ability to translate complex technical concepts for non-technical leadership and explain the broader implications of technical decisions. This is also an ability to listen to and understand newsroom needs that might not be articulated in technical terms.

- Community stewardship: They must not just have a technical understanding of security and privacy, but also an understanding and care for the ethical and legal implications of data handling, reader privacy, choosing values-aligned vendors, and how these things intersect with trust.

- Cross-functional collaboration: The ability to work effectively with Product, Editorial, and Business teams without territorialism. Fundamentally this comes down to an understanding that technology serves the mission, not the other way around, and that we shouldn’t seek to remake the newsroom around technology.

- Pragmatism over dogmatism: A resentment-free understanding of how to build and maintain resilient systems within newsroom budget constraints, which are sometimes very tight. It’s important to take a pragmatic approach to building rather than buying, prioritizing technical debt, and making technology decisions that scale sustainably.

- A long-term mindset: A focus on strategies that will serve the newsroom into the future, rather than succumbing to hype cycles or short-term fads. (Spoiler alert: this usually means betting on the open web, while pragmatically engaging with some shorter-term approaches to address proximal business or reader needs.)

Finally, while a technology leader might be a sole operator in a small newsroom to start with, they’re usually ultimately tasked with building a team. They’re responsible for creating a high-functioning technology team that can operate inside a newsroom culture, with strong empathy, social responsibility, and the potential to form a deep understanding of journalistic needs.

Although it’s better to have one, not every newsroom can hire a full-time technology leader right away. In these cases, hiring either a fractional leader (one who works for less than full-time), or a consultant to act as a sounding board who can guide your technology-adjacent decision-making, is the next best thing.

One thing you shouldn’t worry too much about is matching tech salaries. While it would certainly be better if journalism could match tech compensation — journalists deserve this level of compensation too — there are people who are willing to trade high salaries for mission-driven work. It’s not that organizations can or should hide behind their mission to pay poorly, but journalism is a distinct industry with its own norms, and people from tech will make the leap. I speak from experience here: I dropped a six-figure sum from my salary to work in news because I wanted a position where I felt like I was helping in our current political moment. Let’s acknowledge, though, that only some people can afford to drop their compensation, and this contributes to significant staffing inequalities in the industry.

For the purposes of this discussion, I’m going to assume my hypothetical newsroom has the budget to hire one. But this advice scales down to finding people who can help guide you on a regular basis rather than fully in the trenches with you. In fact, it can be better to start with these kinds of advisors, because they can help you vet an eventual full-time hire.

So, in my hypothetical newsroom that needs to build a technology competence, how do I get started?

Sourcing a newsroom technology leader

Look for the bloggers, the community organizers, and the mission-driven founders.

People who are already writing on their own site or starting open conversations critically about both the human implications of technology issues and the underlying technologies themselves, and building trust-driven communities in the process, are demonstrating a number of important characteristics:

- The ability to communicate technical issues, and their human impacts, well to non-technical colleagues.

- A care for, and participation in, the open web that newsrooms depend on. These people are often already thinking about decentralized infrastructure, reader privacy, and how to build technology that serves people rather than extracting from them.

- Independent thinking that doesn’t just echo company lines or conventional wisdom.

- An understanding of community reactions to technical decisions and discourse.

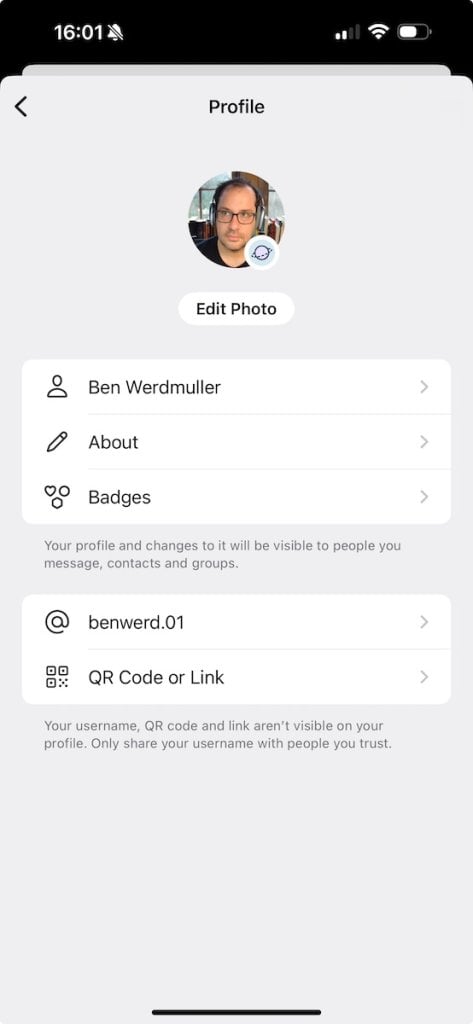

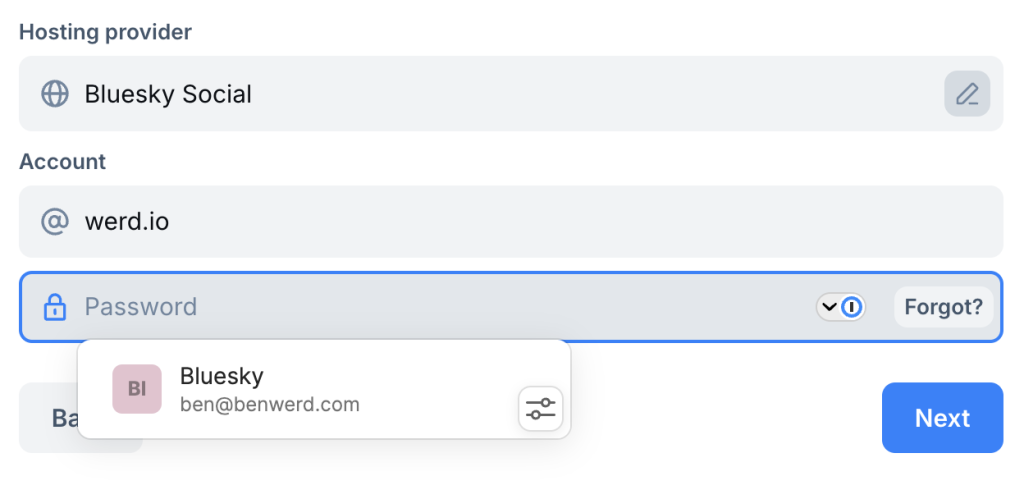

For instance, people writing thoughtful posts on their own sites about how the open social web changes community dynamics — and the protocols that power it — are already engaging with the exact kinds of questions that newsrooms should be thinking about. So are people who are engaging seriously with the ethics of AI rather than joining the hype cycle. People who recognized that the rise of Discord servers and group chats represented a move toward more intimate, trusted information sharing similarly have the ability to predict how changes in the information landscape might affect newsrooms. Depending on your audience, an understanding of how different services and attendant norms are popular in different communities is also important to look for.

Of course, it’s not enough to write, or to organize. You need people who have a track record of not just shipping software (including writing code themselves) but creating technology-informed strategy in resource-constrained, mission-driven environments. That doesn’t need to be a newsroom: it could be a mission-driven startup or a non-profit. You’ll want to interview someone who managed them (which in most cases will be the CEO or Managing Director), as well as someone they managed. In every case you’re looking for:

- A highly empathetic, emotionally intelligent person who isn’t an asshole,

- With a beginner’s mindset,

- Who will do whatever needs to be done to achieve the team’s goals regardless of the nature of the task,

- Who regularly ships both technical and strategic work,

- With enough hands-on technical experience to review code, earn respect from technical staff, evaluate architectural decisions, and understand the implications of technical trade-offs,

- And who takes a “servant leadership” approach to leading and supporting teams and creating a culture of mentorship rather than being a top down-director.

That last one is important, and might be unfamiliar to some newsroom cultures, which may be based on traditional editorial hierarchies. Tech is best created in a collaborative environment of experts, not a top-down, directive culture. While I personally prefer to frame it as empowering leadership rather than servant leadership, the concept is vital: it’s by far the most effective way to create an empathetic, high-performing technology team. (I think it’s probably better for every team, but that might be the subject of another post.)

How not to look for a technology leader

Conversely, two anti-patterns are to prioritize hiring from other newsrooms or people with backgrounds in big tech.

Hiring from other newsrooms perpetuates an insular journalism industry that is not open to outside ideas. While there’s nothing wrong with including people with newsroom backgrounds in the hiring pool, people who don’t have that background shouldn’t be excluded; there are plenty of industries and backgrounds that would bring applicable skills and knowledge into newsrooms, while potentially also bringing in new approaches.

Meanwhile, big tech’s incentives, resources, and constraints are completely different to the newsroom context. An engineering approach that works in a multi-billion-dollar tech company simply doesn’t in a resource-constrained, time-limited environment. That’s not to say that everyone in big tech will be unable to make this shift, but they must know it is a big shift, and they’ve got to be able to lean into it.

Finally, newsrooms still don’t adequately represent the communities they seek to serve, and particularly not at the senior leadership level. This is a fundamental requirement for building trust, and is as important for technology leadership as it is for hiring on the editorial side. More representative teams are wise to the nuances of their audience’s lived experiences. In order for this to be effective, a diverse and inclusive newsroom isn’t enough: a diverse leadership ensures that more representative strategic decisions can be made, and signals to the audience that the newsroom truly represents them.

Technology is not neutral. It must be representative, inclusive, and rooted in service to the public. If we want to rebuild trust and technical resilience in journalism, we must be open to fresh perspectives and hire from outside the usual echo chambers at every level. Journalism and big tech are both fairly exclusionary industries, and not requiring these backgrounds is an ingredient to building a more inclusive hiring pipeline. It’s not enough in itself — intentional outreach to diverse communities is a must, for example — but it’s certainly a prerequisite. Technology as a discipline is not absolved from the need for an inclusive understanding of the impact of leadership decisions, so it’s no less important here.

You do need someone who can build. Avoid candidates who can talk eloquently about technology but have never actually built systems or written production code. Without technical credibility, they’ll struggle to gain respect from technical staff and make informed decisions about complex technical trade-offs — and potentially lead you down some blind alleys.

Supporting a technology leader

Once you’ve found your leader, the most important thing you can do is listen to them — and the most important thing they can do is listen to you.

Newsrooms that have been waiting for a technology function might have a whole backlog of requests. But one of the most common pitfalls for a technology leader is to be treated like a helpdesk: someone who can help execute on existing strategy but isn’t empowered to be a core contributor to new strategy. Given the widely-perceived adverse impact of technology on the journalism industry there may even be some cultural resistance to elevating it into strategic leadership in this way.

Their decision-making power needs to be well-defined. A technology leader’s responsibilities should encompass how software is written, setting engineering standards throughout the organization. In a tech company this is a no-brainer, but newsrooms often have editorial staff who write code, for example to power visualizations or special experiences for specific articles, or to undertake computational research. While this staff probably doesn’t ultimately report to this leader, the way they write software needs to be under their purview too: there’s no sense spending a lot of time making your software fast, modern, and secure if some of the code most likely to be interacted with by audiences doesn’t follow those same rules.

They should also probably be a co-owner of privacy with the organization’s legal function, marrying their own technical understanding of what can a user’s data can be used for with the legal team’s understanding of relevant legislation and case law. Similarly, their understanding of the web landscape should underpin a partnership with the audience teams who work on social media, SEO, and analytics.

But most importantly, they need to be in the room when the senior leadership team meets. They need to be able to bring an informed technology perspective to strategic discussions across the newsroom; advocate for budgeting; make suggestions for ways technology can assist strategic ideas on the table, and how likely future technical developments might affect the newsroom’s strategy; and provide frameworks for other teams to think about how to use technology. As the newsroom sets its goals for the year (your newsroom does that, right?), they need to be a core contributor.

For smaller newsrooms — for example, smaller startups that only have a handful of people — this may still be someone who you contract on a part-time basis to provide these perspectives at particularly impactful moments. For larger newsrooms, it should be someone who’s always there, on the ground with you, standing by your side as you work through every hard decision.

Technology principles for newsrooms

Hiring a leader — and then, in turn, hiring a team — will inevitably take a while. Hiring a consultant who will help you through decisions in the interim is a shorter process, but does take some effort and due diligence in its own right. Here are some principles that will both help you navigate near-term decisions and help evaluate consultants and leaders for fit:

Make human-centered decisions. Looking for ways to use a technology is always backwards. For example, some people would have you believe that if you don’t adopt AI you’ll be left behind. This is marketing! It’s far better to define and scope the real problems you have as an organization and then assess potential solutions, with various technologies in your toolbox as things you might use if there’s a fit. A technology leader can help you assess what’s feasible — what you can build sustainably with the time, team, and resources at your disposal.

Experiment but fail quickly. Sometimes you need the freedom to play around with a solution to see if it has the potential to solve a problem. You can’t know that everything will work out ahead of time — and if you aim for perfection you’ll find yourself paralyzed at the analysis stage. You need to build in explicit permission to run measured experiments (as long as they don’t put your community, your journalism, or your team at risk), but find ways to run scrappy tests to get to a result as quickly as possible. Don’t build something for six months and then figure out whether it’ll work or not.

Pragmatically weigh independence, values, and maintainability. Every technology decision involves trade-offs between owning your infrastructure, aligning with your values, and keeping systems manageable. Perfect independence is impractical: few newsrooms can afford to build their own payment processing or email delivery systems, for example. And because all custom software represents software the newsroom has to maintain, most newsrooms should, on balance, buy far more software than they build.

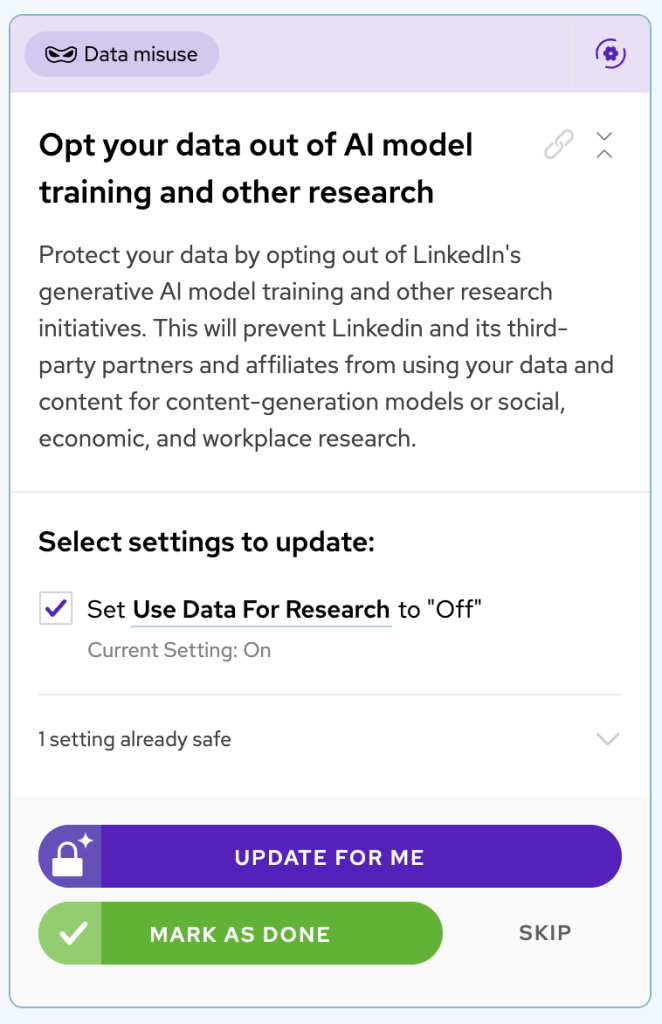

Vendors and platforms should be evaluated based on switching costs, not just current convenience. Can you export your data? Are you locked into proprietary formats? Does this company’s business model align with your editorial mission? Are their values likely to lead to problems down the road?

A good technology leader will help you understand when dependence is acceptable (standardized tools with low switching costs) versus when it’s risky (platforms that provide core functions but will lock you in). The goal isn’t to avoid all external services, but to maintain agency over your most critical functions and ensure you can change course when needed.

Be a good steward of your community’s trust. Be aware of the implications of any data you collect. For example, could a user browsing history function be used to prosecute someone for seeking out abortion information in a state like Texas? Newsrooms have enormous responsibilities to keep people safe. For example, if people are submitting tips or leaks to you, you should never run them through a hosted system like ChatGPT, lest that information be subpoenaed or otherwise obtained by bad actors; if you want to process that data, you need to create local infrastructure with a clear chain of custody and a least privilege approach to security.

Bet on the open web. When faced with technology choices, default to open standards, interoperable systems, and technologies that strengthen the commons rather than creating new silos. In particular, resilience to technology changes means owning your relationship with your audiences.

This means prioritizing RSS over proprietary feeds, open-source content management systems over locked platforms, and web-native publishing over app-only experiences. The open web has proven remarkably resilient, outlasting most proprietary alternatives; harnessing it ensures your content remains accessible regardless of tech industry changes and policy decisions. Meanwhile, the emergent open social web is still small, but is growing: it’s worth investing in it now.

This principle doesn’t mean you need to avoid all proprietary tools, but it does mean ensuring your core content and relationships with your readers exist in formats that you own and will survive platform changes. A technology leader should help you distinguish between tactical use of closed platforms and strategic investments in open infrastructure that you can control and migrate as needed.

Building a technology competence is not optional

Journalism can’t afford to treat technology as an asteroid crashing into the industry.

Building technology competence is about preserving journalism’s essential role in democracy: when newsrooms take control of their technological destiny, they’re better positioned to serve their communities, protect their sources, and maintain the editorial independence that makes accountability journalism possible. The investment in technology leadership is ultimately an investment in the whole newsroom — and because good journalism speaks truth to power and informs the electorate, it’s an investment in democracy itself.

It’s not a small undertaking, but it’s one that every newsroom must embrace in order to secure its future.

Starting a conversation

My experience is in working directly inside two newsrooms — ProPublica, which is where I currently work as the Senior Director of Technology, and before it, as the inaugural CTO at The 19th — as well as over a decade working alongside newsrooms at organizations like Matter Ventures and Latakoo.

If this is a journey you’re embarking on, I’d love to have a conversation and learn more. Leave me your details and I'll reach back out to schedule a chat.

Share this post

Share this post