Applications for Matter Nine are open. It's my job - together with my New York City counterpart, Josh Lucido - to run the process, source candidates, and find the twelve teams that will walk through our San Francisco garage door on August 13.

We get many hundreds of applications for every class, which almost all arrive via our website. The trick is to ensure that everyone is handled fairly, robustly, and with transparency internally to the team. Nothing happens based on a whim, and nobody can fall through the cracks.

Inspired by Nick Grossman's piece about how Union Square Ventures ran their analyst application process, I thought it might be interesting to show off how we're using a collection of tools to drive our Matter accelerator application process.

The application form

The entire application to our accelerator takes place on a single form. We don't ask for a video, although we do want to see links to external resources like your website - and we definitely want to see a deck.

We've used Typeform to power our application form for years. The interface is both simple and pleasant to use. For a while, we had it embedded on our site, but a few users reported that the embed didn't work well on mobile devices, so I decided to link directly to the form instead.

Although the form is designed to be quick to fill in, we ask for a lot of information that will be useful to us as we make our decisions. (It's early stage, so these answers are more than likely imperfect, and that's fine.) Do you know who your user is? Who is the team, and can you execute? What is the mission, and why is that important? What are the trends that make this the right time to start this venture? How do you think you'll make money? We also ask diversity and inclusion questions to help us track our progress on our goal to build a more diverse and inclusive kind of startup community.

All of this data is used to make decisions in the sourcing process individually. It's also used in aggregate to examine trends in the startups that apply to us, and to help us figure out where the gaps in our sourcing might be, as well as how to iterate our process.

So storing it in a way that can be analyzed easily is vital. I don't have time to write my own scripts, and the investments team shouldn't need to have a computer science degree or know how to code in order to do this.

Luckily, AirTable exists.

The database

AirTable looks like a spreadsheet (at least, by default), but is much more like a database. Datasets are split up into "bases", which each contain "tables". Each table in a base can reference each other. And while a traditional database might have field types like text and integers, AirTable adds file-sharing, images, tagging, spreadsheet-style formulae, and a lot more.

Our ecosystem base has two core tables: People and Companies. These contain all the people and all the companies in Matter's ecosystem; not just those who have come through the application process.

To that, we add Applications and Assessments. Almost every question from our form is represented here. For example, we use a tag field (technically a "multi-select") for the areas of focus for the venture, a text field for a link to the deck, and long-text for the qualitative questions.

Our form asks about each member of the team, and these are represented in the People table. Similarly, the startup itself is added to the Company table. Each Application links to a Company, which in turn links to several People. That way, if a company applies to several classes, we can easily see each of them, and see how the company has evolved from one application to the next.

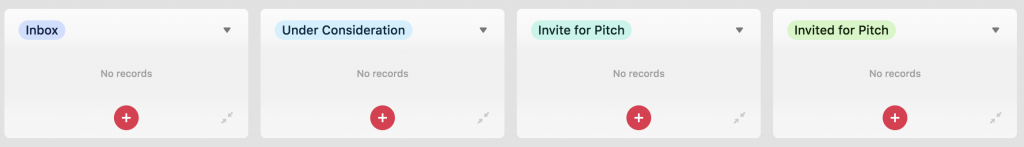

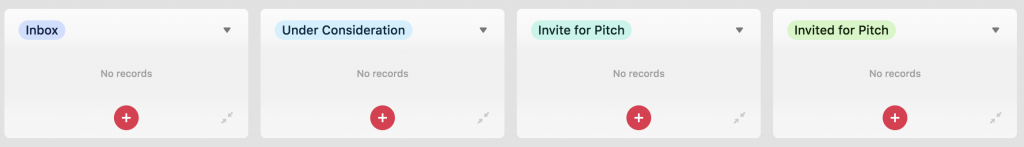

Because AirTable allows us to view a table using a Kanban view, we can easily create a view that starts applications in Inbox, allows us to drag them to Under Consideration, Invite for Pitch, and so on. It looks like this (I've hidden our actual applicants, and there are closer to 15 statuses in total):

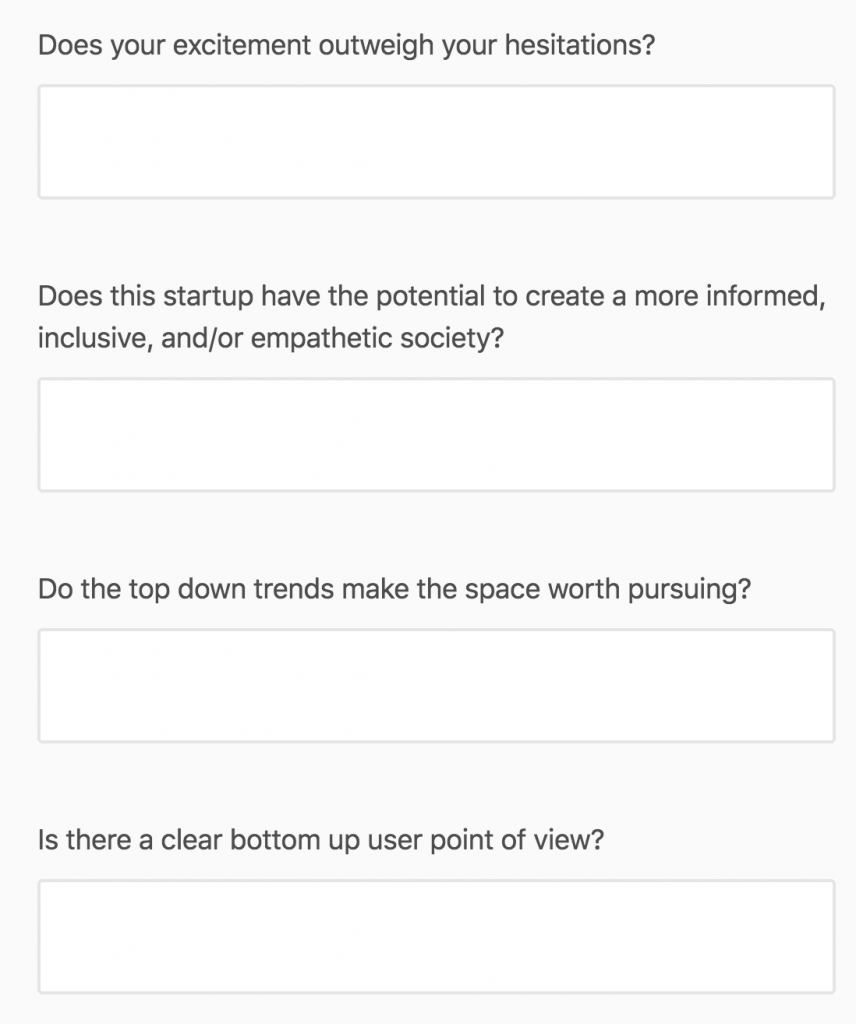

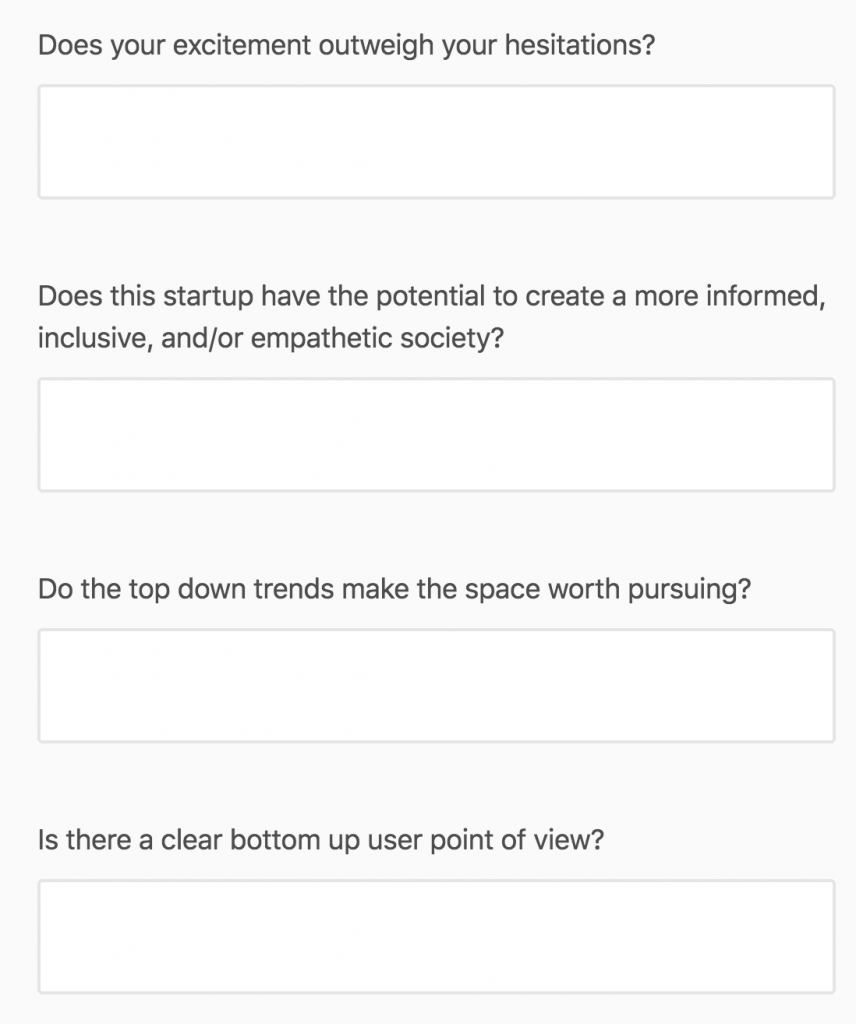

For every single startup that applies, we assess the applicant using a special set of questions that we also use in our Design Reviews throughout the program itself. The answers to these questions get stored in the Assessment table, which links to the Application table. AirTable lets us structure this as a form, which I keep linked from my browser bookmarks tab:

(This is a subset of the questions.)

So to assess an incoming application, and at each stage of the application process, each reviewer's feedback is captured on the form, which is them recorded in AirTable. The investment team meets every week to decide who to advance through the process, based on the feedback.

Connecting Typeform to AirTable (and letting us know about it)

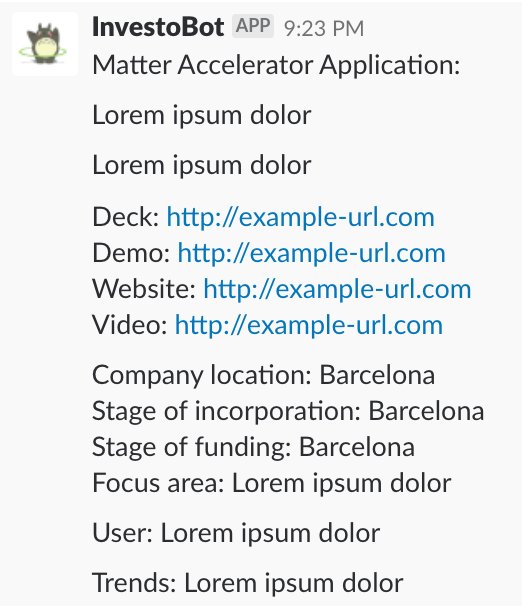

I built a Zapier zap to automatically translate incoming applications from Typeform into AirTable (as well as to notify us in a special investments-incoming channel in Slack).

It looks at the company in the application; if it doesn't already exist in AirTable, it builds a new entry in Companies. Otherwise, it updates the existing one.

It looks at each individual in the startup; if they don't already exist in AirTable, it builds new entries in our People table. Otherwise, it updates the existing ones.

And finally, it always creates a new Application entry, sets the Status to Inbox, and sends a summary of the information to Slack, so we're immediately notified that something new has come in.

In summary

We can now track every application for every company, including all our assessment notes, from a simple interface that also allows us to perform operations on the quantifiable information we capture. From this, we could theoretically create live dashboards that chart our process; we can (and do) also create static summaries of how our applications pool breaks down across themes, stages, team skills, intersectional diversity and inclusion statistics, and more.

I wish some of these steps were easier (for example, if AirTable's own forms were prettier, we might not need to use Zapier etc at all). And there are definitely things we could improve. Still, it's a robust process that allows us to run a very competitive application process in a data-driven way using a small team.

In the future, this structure will allow us to add new interfaces - for example, why not apply to Matter with a conversational chatbot? - that talk to this AirTable back-end. We can also easily perform experiments with the application process to make it more streamlined, brand application forms for specific events or partnerships, or better support certain communities.

In particular, I've been incredibly impressed with AirTable, and I've started recommending it to everyone. I'd love to hear your experiences.

And of course: Applications are open. Join Matter Nine today.

I've always struggled with resumés.

Share this post

Share this post

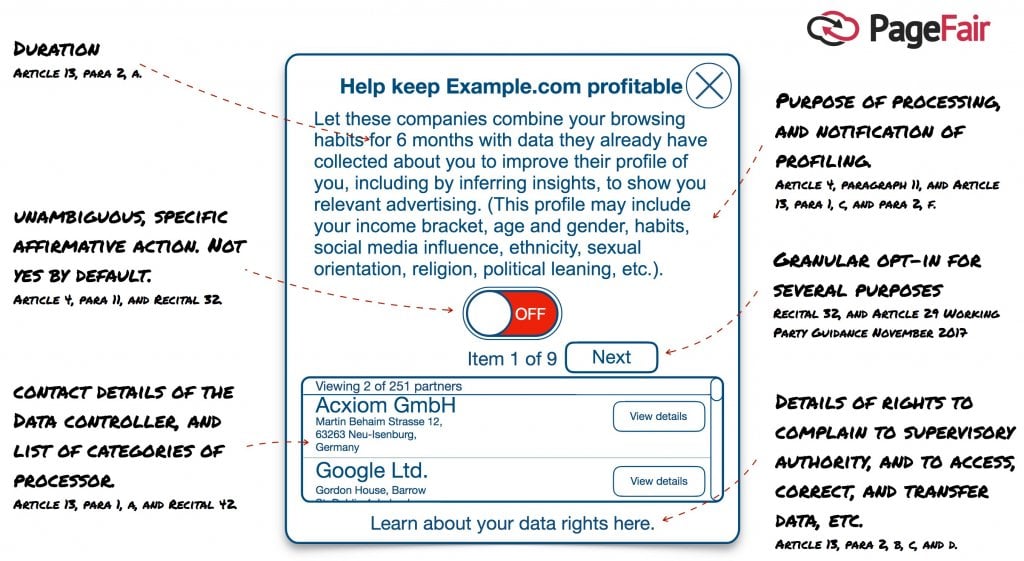

The sample wireframes they've come up with are hilariously onerous, and Europeans will have to opt in on every single site where data is collected. The result will be that almost nobody agrees to give their information universally across all sites, which is the current status quo (because right now, nobody's being asked for anything).

The sample wireframes they've come up with are hilariously onerous, and Europeans will have to opt in on every single site where data is collected. The result will be that almost nobody agrees to give their information universally across all sites, which is the current status quo (because right now, nobody's being asked for anything).