For the last couple of years, fake news has been towards the top of my agenda. As an investor for Matter, it was one of the lenses I used to source and select startups in the seventh and eighth cohorts. As a citizen, disinformation and misinformation influenced how I thought about the 2016 US election. And as a technologist who has been involved in building social networks for 15 years, it has been an area of grave concern.

For the last couple of years, fake news has been towards the top of my agenda. As an investor for Matter, it was one of the lenses I used to source and select startups in the seventh and eighth cohorts. As a citizen, disinformation and misinformation influenced how I thought about the 2016 US election. And as a technologist who has been involved in building social networks for 15 years, it has been an area of grave concern.

Yesterday marked the first day of Misinfocon in Washington DC; while I'm unfortunately unable to attend, I'm grateful that hundreds of people who are much smarter than me have congregated to talk about these issues. They're difficult and there's no push-button answer. From time to time I've seen pitches from people who purport to solve them outright, and people have phoned me to ask for a solution. So far, I've always disappointed them: I'm convinced that the only workable solution is a holistic approach that provides more context.

Of course, it's a terrible term that's being used to further undermine trust in the press. When we talk about "fake news", we're really talking about three things:

Propaganda: systematic propagation of information or ideas in order to encourage or instil a particular attitude or response. In other words: weaponized information to achieve a change of mindset in its audience. The information doesn't have to be incorrect, but it might be.

Misinformation: spreading incorrect information, for any reason. Misinformation isn't necessarily malicious; people can be wrong for a variety of reasons. I'm wrong all the time, and you are too.

Disinformation: disseminating deliberately false information, especially when supplied by a government or its agent to a foreign power or on the media with the intention of influencing policies of those who receive it.

None of them are new, and certainly none of them were newly introduced in the 2016 election. 220 years ago, John Adams had some sharp words in response to Condorcet's comments about journalism:

Writing in the section where the French philosopher predicted that a free press would advance knowledge and create a more informed public, Adams scoffed. “There has been more new error propagated by the press in the last ten years than in an hundred years before 1798,” he wrote at the time.

Condorcet's thoughts on journalism inspired the establishment of authors' rights in France during the French revolution. In particular, the right to be identified as an author was developed not to reward the inventors of creative work, but so that authors and publishers of subversive political pamphlets at the time could be identified and held responsible. It's clear that these conversations have been going on for a long time.

Still, trust in the media is at an all-time low. 66% of Americans say the news media don't do a good job of separating facts from opinion; only 33% feel positively about them. As Brooke Binkowski, Managing Editor of Snopes, put it to Backchannel in 2016:

The misinformation crisis, according to Binkowski, stems from something more pernicious. In the past, the sources of accurate information were recognizable enough that phony news was relatively easy for a discerning reader to identify and discredit. The problem, Binkowski believes, is that the public has lost faith in the media broadly — therefore no media outlet is considered credible any longer.

Credibility is key. In the face of this lack of trust, a good option would be to go back to the readers, understand their needs deeply, and adjust your offerings to take that into account. It's something that Matter helped local news publishers in the US to do recently with Open Matter to great success, and there's more of this from Matter to come. But this is still a minority response. As Jack Shafer wrote in Politico last year:

But criticize them and ask them to justify what they do and how they do it? They go all go all whiny and preachy, wrap themselves in the First Amendment and proclaim that they’re essential to democracy. I won’t dispute that journalists are crucial to a free society, but just because something is true doesn’t make it persuasive.

So what would be more persuasive?

How can trust be regained by the media, and how could the web become more credible?

There are a few ways to approach the problem: from a bottom-up, user driven perspective; from the perspective of the publishers; from the perspective of the social networks used to disseminate information; and from the perspective of the web as a platform itself.

Users

From a user perspective, one issue is that modern readers put far more trust in individuals than they do in brand names. It's been found that users trust organic content produced by people they trust 50% more than other types of media. Platforms like Purple and Substack allow journalists to create their own personal paid subscription channels, leveraging this increased trust. A more traditional publisher brand could create a set of Purple channels for each business, for example.

Publishers

From a publisher perspective, transparency is key: in response to an earlier version of this post, Jarrod Dicker, the CEO of Po.et, pointed out that transparency of effort could be helpful. Here, journalists could show exactly how the sausage was made. As he put it, "here are the ingredients". Buzzfeed is dabbling in these waters with Follow This, a Netflix documentary following the production of a single story each episode.

Publishers have also often fallen into the trap of writing highly emotive, opinion-driven articles in order to increase their pageview rate. Often, this is created by incentives inside the origanization for journalists to hit a certain popularity level for their pieces. While this tactic may help the bottom line in the short term, it comes at the expensive of longer term profits. Those opinion pieces erode trust in the publisher as a source of information, and because the content is optimized for pageviews, it results in shallower content overall.

Social networks

From a social network perspective, fixing the news feed is one obvious way to make swift improvements. Today's feeds are designed to maximize engagement by showing users exactly what will keep them on the platform for longer, rather than a reverse chronological list of content produced by the people and pages they've subscribed to. Unfortunately, this prioritizes highly emotive content over factual pieces, and the algorithm becomes more and more optimized for this over time. The "angry" reacji is by far the most popular reaction on Facebook - a fact that illustrates this emotional power law. As the Pew Research Center pointed out:

Between Feb. 24, 2016 – when Facebook first gave its users the option of clicking on the “angry” reaction, as well as the emotional reactions “love,” “sad,” “haha” and “wow” – and Election Day, the congressional Facebook audience used the “angry” button in response to lawmakers’ posts a total of 3.6 million times. But during the same amount of time following the election, that number increased more than threefold, to nearly 14 million. The trend toward using the “angry” reaction continued during the last three months of 2017.

Inside sources tell me that this trend has continued. Targeted display advertising both encourages the platforms to maximize revenue in this way, and encourages publishers to write that highly emotive, clickbaity content, undermining their own trust in order to make short-term revenue. So much misinformation is simply clickbait that has been optimized for revenue past the need to tell any kind of truth.

It's vital to understand these dynamics from a human perspective: simply applying a technological or a statistical lens won't provide the insights needed to create real change. Why do users share more emotive content? Who are they? What are their frustrations and desires, and how does this change in different geographies and demographics? My friend Padmini Ray Murray rightly pointed out to me that ethnographies of use are vital here.

It's similarly important to understand how bots and paid trolls can influence opinion across a social network. Twitter has been hard at work suspending millions of bots, while Facebook heavily restricted its API to reduce automatic posting. According to the NATO Stratcom Center of Excellence:

The goal is permanent unrest and chaos within an enemy state. Achieving that through information operations rather than military engagement is a preferred way to win. [...] "This was where you first saw the troll factories running the shifts of people whose task is using social media to micro-target people on specific messaging and spreading fake news. And then in different countries, they tend to look at where the vulnerability is. Is it minority, is it migration, is it corruption, is it social inequality. And then you go and exploit it. And increasingly the shift is towards the robotisation of the trolling."

Information warfare campaigns between nations are made possible by vulnerabilities in social networking platforms. Building these platforms has long stopped being a game, simply about growing your user base; they are now theaters of war. Twitter's long-standing abuse problem is now an information warfare problem. Preventing anyone from gaming them for such purposes should be a priority - but as these conflicts become more serious, the more platform changes become a matter of foreign policy. It would be naïve to assume that the big platforms are not already working with governments, for better or worse.

The web as a platform

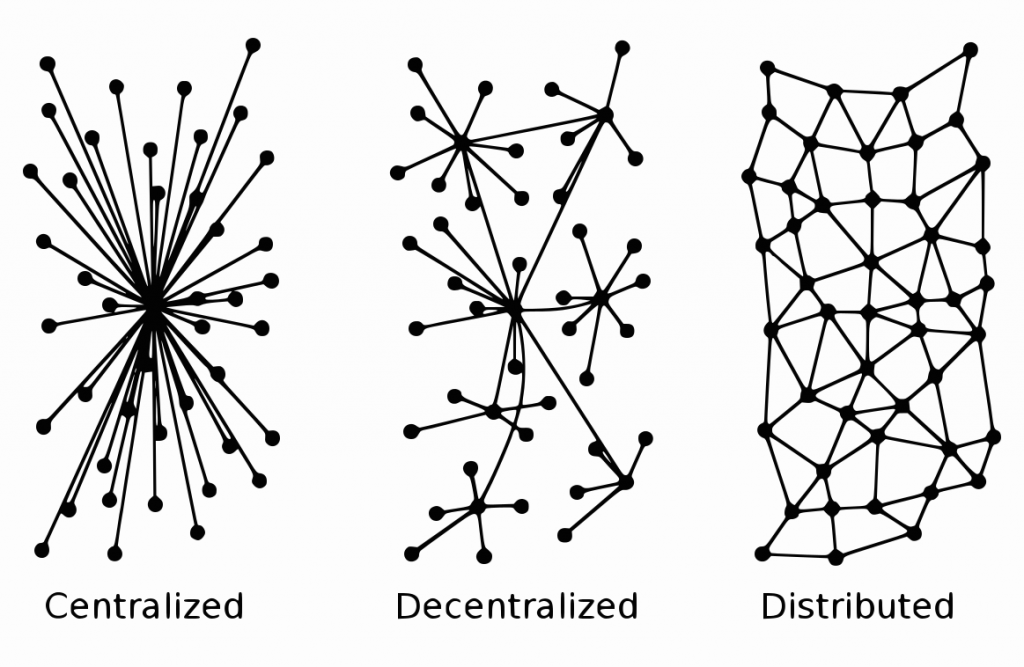

Then there's the web as a platform itself: a peaceful, decentralized network of human knowledge and creativity, designed and maintained for everyone in the world. A user-based solution requires behavior change; a social network solution requires every company to improve its behavior, potentially at the expense of its bottom line. What can be done on the level of the web itself, and the browsers that interpret it, to create a healthier information landscape?

One often-touted solution is to maintain a list of trustworthy journalistic sources, perhaps by rating newsroom processes. Of course, the effect here is direct censorship. Whitelisting publishers means that new publications are almost impossible to establish. That's particularly pernicious because incumbent newsrooms are disproportionately white and male: do we really want to prevent women and people of color from publishing? Furthermore, these publications are often legacy news organizations whose preceived trust derives from their historical control over the means of distribution. The fact that a company had a license to broadcast when few were available, or owned a printing press when publishing was prohibitively expensive for most people, should not automatically impart trust. Rich people are not inherently more trustworthy, and "approved news" is a regressive idea.

Similarly, accreditation would put most news startups out of business. Imagine a world where you need to pay thousands of dollars to be evaluated by a central body, or web browsers and search engines around the world would disadvantage you in comparison to people who had shelled out the money. The process would be subject to ideological bias from the accrediting body, and the need for funds would mean that only founders from privileged backgrounds could participate.

I recently joined the W3C Credible Web Community Group and attended the second day of its meeting in San Francisco, and was impressed with the nuance of thought and bias towards action. Representatives from Twitter, Facebook, Google, Mozilla, Snopes, and the W3C were all in attendance, discussing openly and directly collaborating on how their platforms could help build a more credible web. I'm looking forward to continuing to participate.

It's clearly impossible for the web as a platform to objectively report that a stated fact is true or false. This would require a central authority of truth - let's call it MiniTrue for short. It may, however, be possible for our browsers and social platforms to show us the conversation around an article or component fact. Currently, links on the web are contextless: if I link to the Mozilla Information Trust Initiative, there's no definitive way for browsers, search engines or social platforms to know whether I agree or disagree with what is said within (for the record, I'm very much in agreement - but a software application would need some non-deterministic fuzzy NLP AI magic to work that out from this text).

Imagine, instead, if I could highlight a stated fact I disagree with in an article, and annotate it by linking that exact segment from my website, from a post on a social network, from an annotations platform, or from a dedicated rating site like Tribeworthy. As a first step, it could be enough to link to the page as a whole. Browsers could then find backlinks to that segment or page and help me understand the conversation around it from everywhere on the web. There's no censoring body, and decentralized technologies work well enough today that we wouldn't need to trust any single company to host all of these backlinks. Each browser could then use its own algorithms to figure out which backlinks to display and how best to make sense of the information, making space for them to find a competitive advantage around providing context.

Startups

I've come to the conclusion that startups alone can't provide the solutions we need. They do, however, have a part to play. For example:

A startup publication could produce more fact-based, journalistic content from underrepresented perspectives and show that it can be viable by tapping into latent demand. eg, The Establishment.

A startup could help publications rebuild trust by bringing audiences more deeply into the process. eg, Hearken.

A startup could help to build a data ecosystem for trust online, and sell its services to publications, browsers, and search engines alike. eg, Factmata and Meedan.

A startup could establish a new business model that prioritizes something other than raw engagement. eg, Paytime and Purple.

But startups aren't the solution alone, and no one startup can be the entire solution. This is a problem that can only be solved holistically, with every stakeholder in the ecosystem slowly moving in the right direction.

It's a long road

These potential technology solutions aren't enough on their own: fake news is primarily a social problem. But ecosystem players can help.

Users can be wiser about what they share and why - and can call out bad information when the see it. Those with the means can provide patronage to high quality news sources.

Publishers can prioritize their own longer term well-being by producing fact-based, deeper content and optimizing for trust with their audience.

Social networks can find new business models that aren't incentivized to promote clickbait.

And by empowering readers with the ability to fact check for themselves and understand the conversational context around a story, while continuing to support the web as an open platform where anyone can publish, we can help create a web that disarms the people who seek to misinform us by separating us from the context we need.

These are small steps - but together, taken as a whole, steps in the right direction.

Thank you to Jarrod Dicker and Padmini Ray Murray for commenting on an earlier version of this post.

Share this post

Share this post So I thought I'd add this blog to it, too. I signed up, and it turns out that they would vastly prefer you to use that proprietary API:

So I thought I'd add this blog to it, too. I signed up, and it turns out that they would vastly prefer you to use that proprietary API:

Lately I've increasingly encountered arguments for "equality of opportunity vs equality of outcome", which is usually shorthand for a bunch of nastier opinions held by people who don't think we should be aiming for a more inclusive society. As far as I can tell, this is largely due to the rising popularity of Jordan Petersen, a conservative pseudointellectual who is fast becoming the voice of unreconstructed dudes who like to complain about feminism.

Lately I've increasingly encountered arguments for "equality of opportunity vs equality of outcome", which is usually shorthand for a bunch of nastier opinions held by people who don't think we should be aiming for a more inclusive society. As far as I can tell, this is largely due to the rising popularity of Jordan Petersen, a conservative pseudointellectual who is fast becoming the voice of unreconstructed dudes who like to complain about feminism.

I enjoyed the contrast between

I enjoyed the contrast between  There's rightly been a lot of discussion over the last few weeks about

There's rightly been a lot of discussion over the last few weeks about