I’m focusing on the intersection of technology, media, and democracy. Subscribe by email to get every update.

This is my monthly roundup of the links, books, and media I found interesting. Do you have suggestions? Let me know!

Books

Nonfiction

Poverty, by America, by Matthew Desmond. More of a searing polemic than its predecessor; I nonetheless wish it could be required reading. Perhaps the work Desmond describes isn’t possible - but it is the work that needs to be done in order to end poverty in America. Its impossibility is a symptom of an ugliness that cuts to the country’s core.

Notable Articles

AI

"the secret list of websites". “Google is a portal to the web. Google is an amazing tool for finding relevant websites to go to. That was useful when it was made, and it’s nothing but grown in usefulness. Google should be encouraging and fighting for the open web. But now they’re like, actually we’re just going to suck up your website, put it in a blender with all other websites, and spit out word smoothies for people instead of sending them to your website. Instead.”

ChatGPT is taking ghostwriters’ jobs in Kenya. “Collins now fears that the rise of AI could significantly reduce students’ reliance on freelancers like him in the long term, affecting their income. Meanwhile, he depends on ChatGPT to generate the content he used to outsource to other freelance writers.”

AI Drake just set an impossible legal trap for Google. “Okay, now here’s the problem: if Ghostwriter977 simply uploads “Heart on my Sleeve” without that Metro Boomin tag, they will kick off a copyright war that pits the future of Google against the future of YouTube in a potentially zero-sum way. Google will either have to kneecap all of its generative AI projects, including Bard and the future of search, or piss off major YouTube partners like Universal Music, Drake, and The Weeknd.”

See the websites that make AI bots like ChatGPT sound so smart. “Also high on the list: a notorious market for pirated e-books that has since been seized by the U.S. Justice Department. At least 27 other sites identified by the U.S. government as markets for piracy and counterfeits were present in the data set.”

Google Bard AI Chatbot Raises Ethical Concerns From Employees. “In February, one employee raised issues in an internal message group: “Bard is worse than useless: please do not launch.” The note was viewed by nearly 7,000 people, many of whom agreed that the AI tool’s answers were contradictory or even egregiously wrong on simple factual queries.”

Sony World Photography Award 2023: Winner refuses award after revealing AI creation. “In a statement shared on his website, Eldagsen admitted he had been a “cheeky monkey”, thanking the judges for “selecting my image and making this a historic moment”, while questioning if any of them “knew or suspected that it was AI-generated”. “AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this,” he continued. “They are different entities. AI is not photography. Therefore I will not accept the award.””

How WIRED Will Use Generative AI Tools. “This is WIRED, so we want to be on the front lines of new technology, but also to be ethical and appropriately circumspect. Here, then, are some ground rules on how we are using the current set of generative AI tools. We recognize that AI will develop and so may modify our perspective over time, and we’ll acknowledge any changes in this post.”

A Computer Generated Swatting Service Is Causing Havoc Across America. “In fact, Motherboard has found, this synthesized call and another against Hempstead High School were just one small part of a months-long, nationwide campaign of dozens, and potentially hundreds, of threats made by one swatter in particular who has weaponized computer generated voices. Known as “Torswats” on the messaging app Telegram, the swatter has been calling in bomb and mass shooting threats against highschools and other locations across the country.”

Publishers create task forces to oversee AI programs. ““My CEO is fucking obsessed with AI… but I’m not totally convinced,” said one publishing executive on the condition of anonymity.”

We need to tell people ChatGPT will lie to them, not debate linguistics. “We should be shouting this message from the rooftops: ChatGPT will lie to you.”

ChatGPT is making up fake Guardian articles. Here’s how we’re responding. “But the question for responsible news organisations is simple, and urgent: what can this technology do right now, and how can it benefit responsible reporting at a time when the wider information ecosystem is already under pressure from misinformation, polarisation and bad actors.”

Clearview AI scraped 30 billion images from Facebook and other social media sites and gave them to cops: it puts everyone into a 'perpetual police line-up'. “A controversial facial recognition database, used by police departments across the nation, was built in part with 30 billion photos the company scraped from Facebook and other social media users without their permission, the company’s CEO recently admitted, creating what critics called a “perpetual police line-up,” even for people who haven’t done anything wrong.”

What if Bill Gates is right about AI? “So as an exercise, let’s grant his premise for a moment. Let’s treat him as an expert witness on paradigm shifts. What would it mean if he was right that this is a fundamental new paradigm? What can we learn about the shape of AI’s path based on the analogies of previous epochs?”

Business

The EU Suppressed a 300-Page Study That Found Piracy Doesn’t Harm Sales. “The European Commission paid €360,000 (about $428,000) for a study on how piracy impacts the sales of copyrighted music, books, video games, and movies. But the EU never shared the report—possibly because it determined that there is no evidence that piracy is a major problem.”

Online Ads Are Serving Us Lousy, Overpriced Goods. “The products shown in targeted ads were, on average, roughly 10 percent more expensive than what users could find by searching online. And the products were more than twice as likely to be sold by lower-quality vendors as measured by their ratings by the Better Business Bureau.”

Climate

Is PFAS pollution a human rights violation? These activists say yes. ““We live in one of the richest nations in the world, yet our basic human rights are being violated,” Emily Donovan, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear, said in a statement. “We refuse to be a sacrifice zone. Residents here are sick and dying and we continue to lack equitable access to safe water in our region, or the necessary health studies to truly understand the impact from our chronic PFAS exposures.””

Climate Fiction Will Not Save Us. “What these examples reveal, too, is that all fiction is political, even if just by turning away from this and deciding to show us that instead. But it is not a policy map, which isn’t a failing so much as a condition of most fiction as an art form having other obligations to fulfill than, say, those embodied by a scientist, who does not make things up for a living (even though the two warring conditions may coexist in the same person).”

Culture

How Philly Cheesesteaks Became a Big Deal in Lahore, Pakistan. “Pakistan’s fast-food boom of the 1990s and 2000s overlapped with a rise in Pakistanis traveling to the U.S. for study, work, business and immigration. As a result, many of the food establishments launched in Pakistan at the turn of the millennium were brimming with ideas that those visiting the U.S. brought back with them. The cheesesteak was one of these.”

Judy Blume is reaching a new generation — even as her books are targeted by bans. “Blume’s books are still considered trailblazing for the way they talked about burgeoning sexuality without judgment, and the everyday lives of young people as complicated, difficult and worthy of attention, experts said. The same could be said of so many of the books routinely censored today. The book ban surge in school districts across the country “can be depressing on any given day,” Finan said. Which is why, he stressed, Blume matters so much right now.”

Tiny Technicalities: The Pronoun Update. “The trouble is: the very people that most feel a need to escape are the ones that need to escape from the negativity, from having their identity and their body not recognized. Is that really “gender activism”, or is it just people who are being forced to take part in a convoluted political discussion, the bottom line of which should be simple: people should get to be who they really are, and people should get to be happy with their identities and their lives.”

Dril Is Everyone. More Specifically, He’s a Guy Named Paul. “Paul Dochney, who is 35, does not, in fact, look like a mutant Jack Nicholson. He has soft features and a gentle disposition and looks something like a young Eugene Mirman. It’s difficult to say what I expected to find sitting across from me, but it wasn’t this. Looking at him, you’d never presume that this was the person who made candle purchasing a matter of financial insecurity.”

Jerry Craft drew a positive Black story in 'New Kid.' Then the bans began. “The ALA director says about 40 percent of the challenges are to “100 titles or more at one time” rather than an individual title challenged by a lone concerned parent. “What we’re seeing is political advocacy groups trying to suppress the voices of marginalized groups and prevent students the access to different viewpoints.””

The Costs of Becoming a Writer. “I am aware that focusing on individual responsibility can obscure the reality of broken systems. That neither my parents nor I am to blame for what they were up against. That it was always going to be beyond my capacity to provide and pay for all their care out of pocket when they had significant medical needs and, for many years, no healthcare coverage. But I was—I am—their only child, and I not only wanted but expected to be of more help to them. I didn’t know that we would run out of time.“

Jackson Heights: The neighbourhood that epitomises New York. I adore New York City. This is why.

Democracy

A Pharmacist Is Helping Clear the Way for Lethal Injections. “I conclude that they did experience extreme pain and suffering through the execution process.”

Courts Are Beginning to Prevent the Use of Roadside Drug Tests. “Each of the cases had relied on the results of chemical field test kits used by corrections officers at nearby state prisons. The kits indicated crumbs and shreds of paper that guards found on the inmates contained heroin and amphetamine. But a state forensic laboratory later analyzed the debris utilizing a far more reliable test and found no trace of illegal drugs. The defendants were factually innocent.”

Ranked-choice voting is growing – along with efforts to stop it. “”Entrenched interests are recognizing that they would like to stop ranked-choice voting from moving forward because it has such a profound impact in shifting power dynamics,” said Joshua Graham Lynn, chief executive officer of RepresentUs, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for democracy-related policy. “They, of course, benefit from the power dynamics the way they are.””

Americans are demanding change on guns ahead of Election 2024. “Some lawmakers offer only thoughts and prayers, and others insist that something must be done. But the unrelenting toll of gun violence across the country has resulted in incremental change at best in a sharply partisan Congress and inaction more broadly, particularly in red states. The nation’s status quo is unacceptable to many Americans, while talks of reform only affirm others’ commitment to the Second Amendment.”

French publisher arrested in London on terrorism charge. “A French publisher has been arrested on terror charges in London after being questioned by UK police about participating in anti-government protests in France.” Scandalous.

ICE Records Reveal How Agents Abuse Access to Secret Data. “ICE investigators found that the organization’s agents likely queried sensitive databases on behalf of their friends and neighbors. They have been investigated for looking up information about ex-lovers and coworkers and have shared their login credentials with family members. In some cases, ICE found its agents leveraging confidential information to commit fraud or pass privileged information to criminals for money.”

Oklahoma officials recorded talking about killing reporters and complaining they can no longer lynch Black people. “The governor of Oklahoma has called for the resignations of the sheriff and other top officials in a rural county after they were recorded talking about “beating, killing and burying” a father/son team of local reporters — and lamenting that they could no longer hang Black people with a “damned rope.””

Clarence Thomas Secretly Accepted Luxury Trips From GOP Donor. “These trips appeared nowhere on Thomas’ financial disclosures. His failure to report the flights appears to violate a law passed after Watergate that requires justices, judges, members of Congress and federal officials to disclose most gifts, two ethics law experts said. He also should have disclosed his trips on the yacht, these experts said.”

ICE Is Grabbing Data From Schools and Abortion Clinics. “The outlier cases include custom summonses that sought records from a youth soccer league in Texas; surveillance video from a major abortion provider in Illinois; student records from an elementary school in Georgia; health records from a major state university’s student health services; data from three boards of elections or election departments; and data from a Lutheran organization that provides refugees with humanitarian and housing support.”

Labor

Discrimination against moms is rampant in workplaces. “Moms are still often laid off while on parental leave, pushed out of workplaces and subjected to stereotypes about their competency. But with few legal protections, attorneys say most cases go unreported.”

CEO Celebrates Worker Who Sold Family Dog After He Demanded They Return to Office. “In a virtual town hall last week, the CEO of a Utah-based digital marketing and technology company, who is forcing employees to return to the office, celebrated the sacrifice of a worker who had to sell the family dog as a result of his decisions. He also questioned the motives of those who disagreed, accusing some of quiet quitting, and waxed skeptical on the compatibility of working full time with serving as a primary caregiver to children.”

How Important Is Paternity Leave? “Maternity leave should still be our top policy priority in the U.S. However, paternity leave is an important next step. In the shorter term, for individuals and companies, these results are worth considering. Flexibility for overlapping leave in the short term, and concentrated father time in the first year, both appear to have positive impacts.”

Julie Su prioritized workers long before U.S. Labor Department nomination. “The press called it the great resignation. Many of our low-wage worker members are calling it the great revolution.”

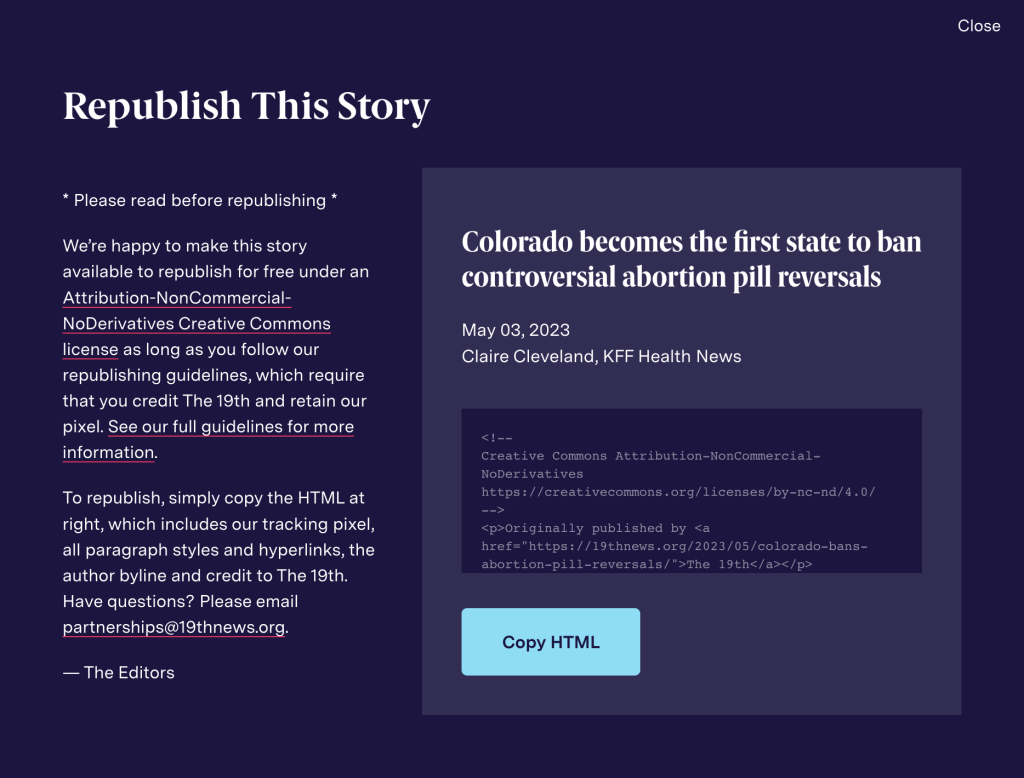

Media

How newsrooms pay journalist-coders today. “The overall findings from the recent survey showed changes in demographics and priorities for the news nerd community. We hope that the salary data can now serve as one piece of the puzzle to improve equity in newsroom culture.”

Inside Rupert Murdoch’s Succession Drama. “While the finale unfolds, Murdoch is trying to prove he has one last act in him. But his erratic performance, which has thrown his personal life and media empire into disarray, has left even those in his orbit wondering if he’s lost the plot.”

NPR to stop using Twitter, says account's new label misleading. “National Public Radio (NPR) will no longer post content to its 52 official Twitter feeds in protest against a label by the social media platform that implies government involvement in the U.S. organization’s editorial content.”

Why KCRW is leaving Twitter — and where else to find us. “Twitter has falsely labeled NPR as “state-affiliated media.” It’s a term the platform applies to propaganda outlets in countries without a free press, a guaranteed right in the United States. This is an attack on independent journalism, the very principle that defines public media. Twitter has since doubled down on the label, which is outrageous and further undermines the credibility of the platform.”

Why journalists can't quit Twitter. “For the moment, though, Musk has learned the same lesson Jack Dorsey did: Twitter is extremely hard to kill. And for the journalists who have come to rely on it, there is almost no indignity they won’t suffer to get their fix.”

Science

The ‘invented persona’ behind a key pandemic database. “Bogner’s apparent alter ego is only one of many concerning findings about his life and the way he runs GISAID that emerged during a Science investigation involving interviews with more than 70 sources, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, and reviews of hundreds of emails and dozens of documents. Scientists and funders have also started to ask hard questions about Bogner and his creation, because GISAID’s mission could hardly be more critical: to prevent, monitor, and fight epidemics and pandemics.”

Society

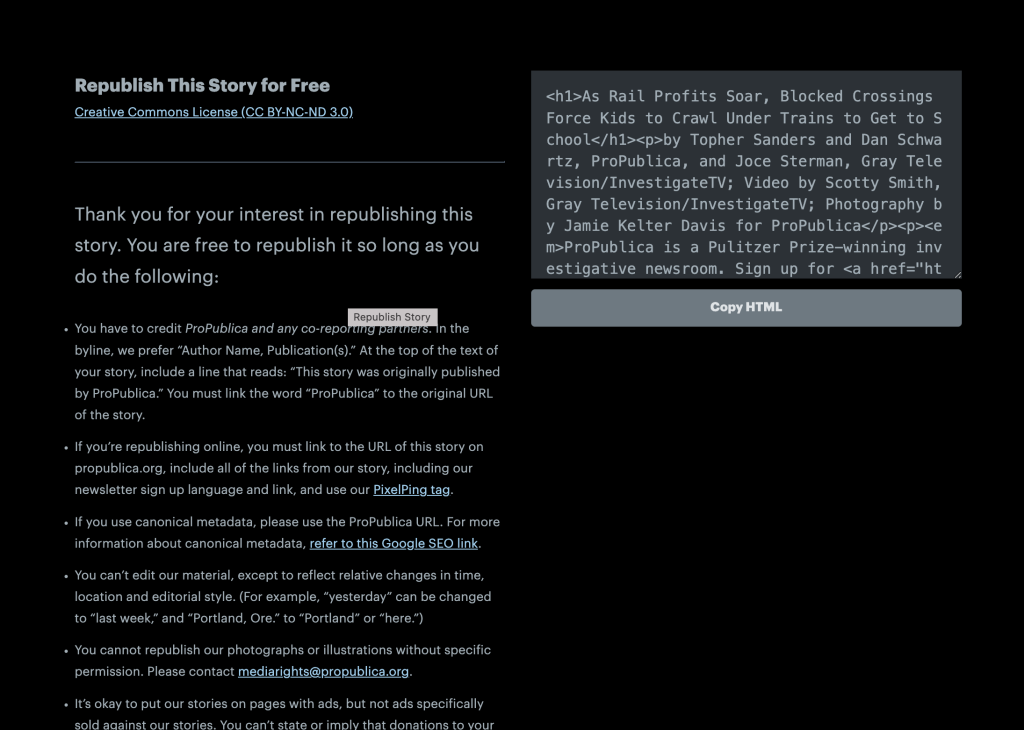

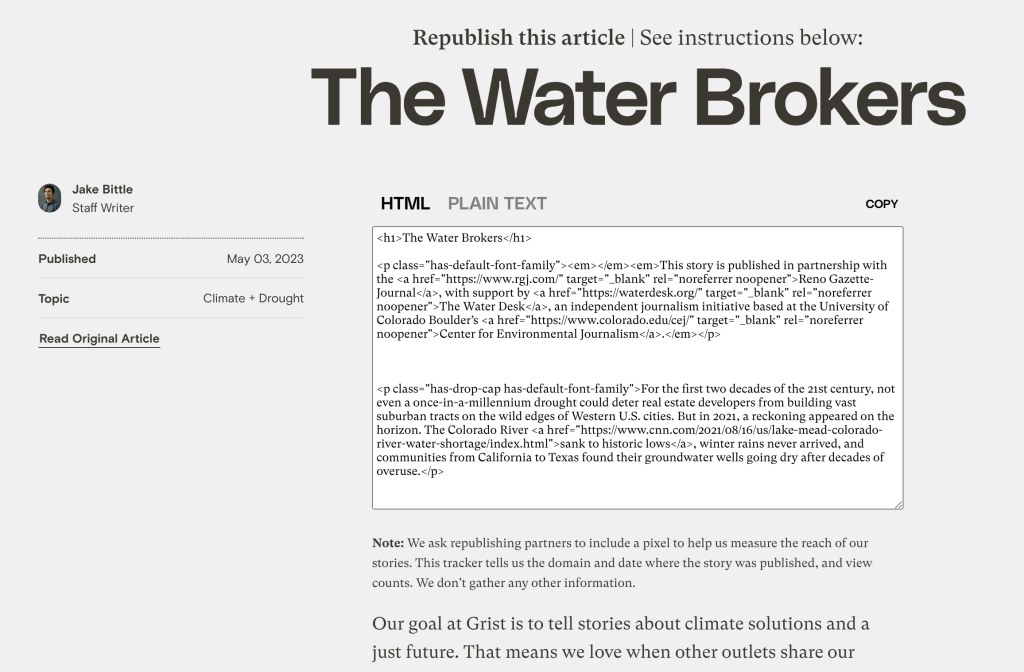

Blocked Crossings Force Kids to Crawl Under Trains to Get to School. “Lamira Samson, Jeremiah’s mother, faced a choice she said she has to make several times a week. They could walk around the train, perhaps a mile out of the way; she could keep her 8-year-old son home, as she sometimes does; or they could try to climb over the train, risking severe injury or death, to reach Hess Elementary School four blocks away.” A close schoolfriend of mine died when he crossed under a train, and these photos made my heart stop.

Why Silicon Valley is bringing eugenics back. “We can debate whether Musk knows what he’s doing here — it’s obvious he thinks he’s much brighter than he is — but he’s very clearly laundering eugenicist and white nationalist views. When he refers to “smart” people needing to have more “smart” kids, he’s suggesting that IQ — a deeply flawed concept in itself — is passed through genetics, and when he warns about the crumbling of civilization, it’s hard not to hear the deeply racist concerns about the decline of the white race that have become far too common in recent years.”

Gun Violence Is Actually Worse in Red States. It’s Not Even Close. “In reality, the region the Big Apple comprises most of is far and away the safest part of the U.S. mainland when it comes to gun violence, while the regions Florida and Texas belong to have per capita firearm death rates (homicides and suicides) three to four times higher than New York’s. On a regional basis it’s the southern swath of the country — in cities and rural areas alike — where the rate of deadly gun violence is most acute, regions where Republicans have dominated state governments for decades.”

Nonprofits Led by People of Color Get Less Funding Than Others. “Nonprofits that serve people of color or are led by nonwhite executive directors have a harder time getting the funding they need than other organizations, increasing their financial hardships.”

Coloring the Past. “The following images are originally from 1897-1973. After noticing how much more responsive audiences are to color photos, Eli decided to work on past images from queer and trans history. During a time when politicians can openly argue trans people did not exist until 2015, it is important to use reminders like these that we have always been here.”

Technology

Six Months In: Thoughts On The Current Post-Twitter Diaspora Options. “There have been a bunch of attempts at filling the void left by an unstable and untrustworthy Twitter, and it’s been fascinating to watch how it’s all played out over these past six months. I’ve actually enjoyed playing around with various other options and exploring what they have to offer, so wanted to share a brief overview of current (and hopefully future options) for where people can go to get their Twitter-fix without it being on Twitter.”

Google Authenticator finally, mercifully adds account syncing for two-factor codes. “IT employees must be crying tears of joy.”

Smartphones With Popular Qualcomm Chip Secretly Share Private Information With US Chip-Maker.“During our security research we found that smart phones with Qualcomm chip secretly send personal data to Qualcomm. This data is sent without user consent, unencrypted, and even when using a Google-free Android distribution. This is possible because the Qualcomm chipset itself sends the data, circumventing any potential Android operating system setting and protection mechanisms. Affected smart phones are Sony Xperia XA2 and likely the Fairphone and many more Android phones which use popular Qualcomm chips.

The Future of Social Media Is a Lot Less Social. “Social media is, in many ways, becoming less social. The kinds of posts where people update friends and family about their lives have become harder to see over the years as the biggest sites have become increasingly “corporatized.” Instead of seeing messages and photos from friends and relatives about their holidays or fancy dinners, users of Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Twitter and Snapchat now often view professionalized content from brands, influencers and others that pay for placement.”

Parler Shut Down by New Owner: ‘A Twitter Clone’ for Conservatives Is Not a ‘Viable Business’. ““No reasonable person believes that a Twitter clone just for conservatives is a viable business any more,” Arlington, Va.-based digital media company Starboard said in announcing Friday that it had acquired Parler.”

GitHub Accelerator: our first cohort and what's next. “The projects cover a wide range of potential open source business models, and while many of the maintainers are looking for a way to sustain their open source work full-time, they have differing goals for what financial stability could look like for them. We’re here to help support projects testing new ways to bring in durable streams of funding for open source—and to help share those learnings back with the community.”

Is Substack Notes a ‘Twitter clone’? We asked CEO Chris Best. “You know this is a very bad response to this question, right? You’re aware that you’ve blundered into this. You should just say no. And I’m wondering what’s keeping you from just saying no.”

Feedly launches strikebreaking as a service. “In a world of widespread, suspicionless surveillance of protests by law enforcement and other government entities, and of massive corporate union-busting and suppression of worker organizing, Feedly decided they should build a tool for the corporations, cops, and unionbusters.”

Elon Musk seeks to end $258 billion Dogecoin lawsuit. “Elon Musk asked a U.S. judge on Friday to throw out a $258 billion racketeering lawsuit accusing him of running a pyramid scheme to support the cryptocurrency Dogecoin.” Related: Twitter’s logo changed to Doge as soon as this story broke - almost as if Musk wanted to bury it.

Share this post

Share this post