Prologue:

The first time I ever visited South Park, the tiny patch of grass in downtown San Francisco that the Matter garage would later back onto, Biz Stone bought me a coffee. We circled the park and talked about Elgg, our open source social networking product, and Twitter, the startup he was working on at the time.

The most important piece of advice he gave us was this: hold something back. It's fine to open source your code, to release an open product, but you've got to hold back the thing that will make you valuable.

This was the most important advice we received about Elgg. We ignored it completely.

Six years later: September 2014.

Erin and I stepped down from the Paley Center stage in New York, exhausted. Most accelerators have one demo day. Because Matter is so closely tied to both media and technology, it has two: one at the Folsom Street Foundry in San Francisco, in the heart of SoMa, and the other in New York, the city where most of America's media companies call home.

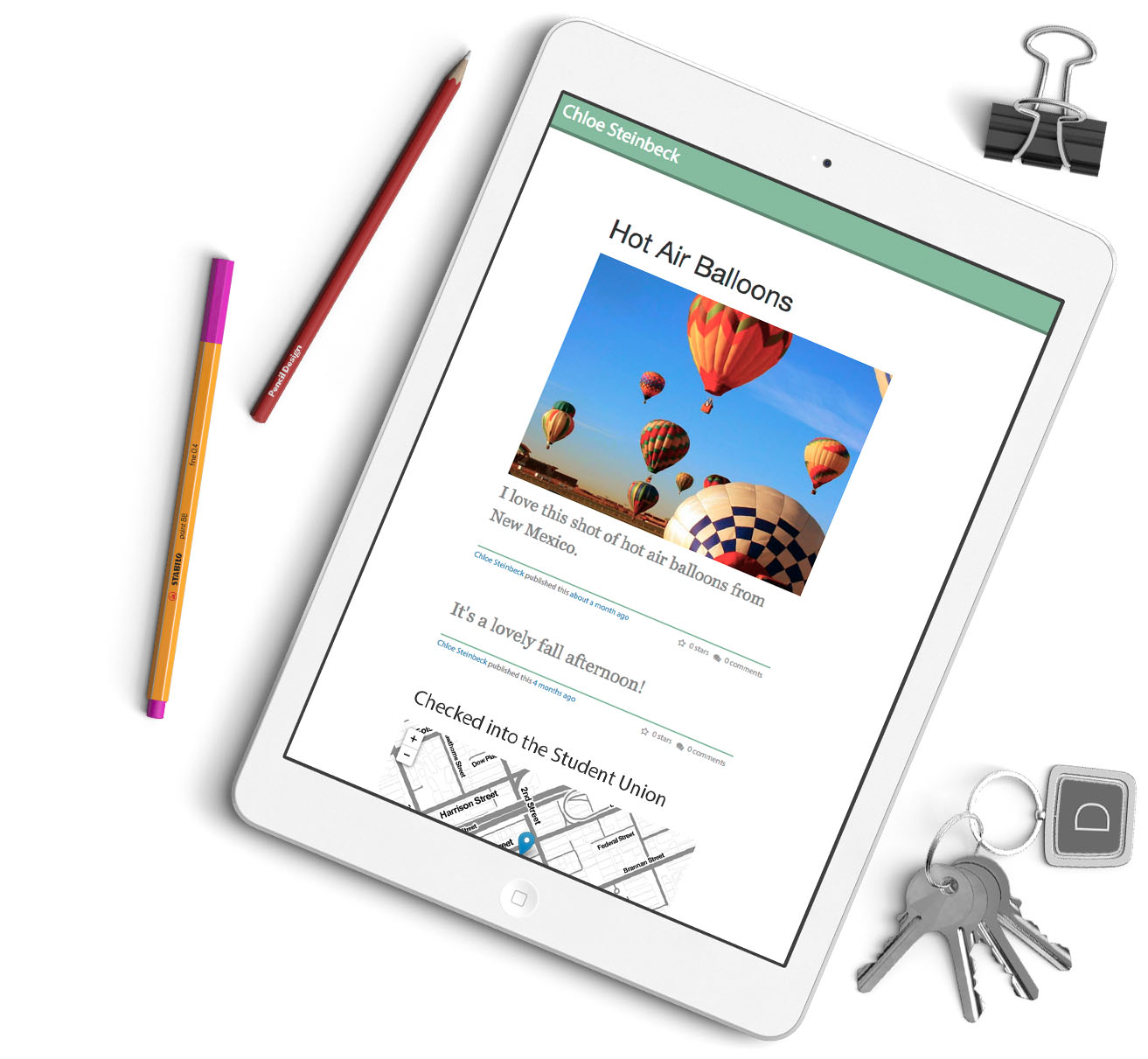

Known, we told an audience of media luminaries like Jeff Jarvis and industry investors, was a way for post-secondary students to save their coursework, notes and discussions on a site that they controlled. In a world where students are used to delightful apps and beautiful user experiences, the Learning Management Systems used by 93% of institutions are an abomination that actively hinder learning. Worse, when a course is over, all of the discussions and resources that were collaboratively made by the class are deleted forever. With Known, students can publish to their own site, and syndicate to these other platforms, allowing them to take control over their learning using a beautiful, mobile-first user interface.

Better yet, we told the audience, Known has an open source core. We know that one size doesn't fit all in education. With Known, every single feature has an API endpoint, and every single feature can be customized to fit both the needs of the institution and the student. The first pilot is happening right now, and we're getting great feedback.

Applause. Seven minutes later, we were done. This was day zero for our company: the next day, the hard work would begin.

Skip forward: September 2015.

I looked around the table at Garaje. Most of the alumni from Matter's third class were here, and had great stories to tell: Musey were thriving and building beautiful design apps; LocalData were helping to improve American cities; Louder were preparing their acquisition by Change.org. Over in New York, Stringr were delivering video to more and more news stations.

In some ways, Known was doing well. Our software was powering tens of thousands of websites. We had received great coverage at our launch, and continued to get fantastic feedback from educators all over the world. People were using Known to teach on five continents.

Yet at the same time, we didn't know how we were going to pay rent, and growth was linear. For a project, we were doing well. For a company, we weren't doing well - and there were still only two of us.

What went wrong?

First, you have to understand open source.

Open source is best defined by its four freedoms, which are inspired by Roosevelt's declaration of the four freedoms that every human should be able to enjoy. These dictate that you should be able to:

0. Run the program as you wish, for any purpose

1. Study how it works, and modify its function

2. Redistribute copies “so you can help your neighbor”

3. Distribute copies of your modified versions

The intention is that open source software is free as in speech: it grants you liberties over the code you run that you might not get with other products.

Unfortunately, the word "free" is overloaded: it has multiple possible meanings. In reality, open source has become synonymous with free as in beer: software that you can use without incurring any direct licensing costs.

Our strategy was to create an open core that people could freely distribute, and then layer premium services over the top. If you didn't want to worry about managing servers, we had an excellent SaaS product. If you didn't want to worry about managing APIs to third-party platforms, we offered Convoy. Finally, we wanted to provide access to a network of trusted consultants who could create customizations for institutional customers.

Our utopian vision was to have organic growth through sharing, leading to institutional customers. This didn't happen - at least, not as fast as we needed it to.

Second, you have to understand startups.

We have exact numbers internally, but a good rule of thumb in San Francisco is that, to break even, we need to bring in $10,000 per employee per month. This covers below market rate salaries, as well as all the overheads you incur when you're running a business (for example, taxes and moderate infrastructure costs). It doesn't cover some of the extra investment you really need to put into sales, marketing and product development.

To be relatively comfortable as a two-person company, we need to clear $240,000 per year. That's a tough ask for many businesses, which is one reason why investors are useful: they back your team and put money into your company, making a bet that you'll be profitable later on and will be able to pay them back and then some.

Consider, also, that most teams are not limited to two people. I've got a development and product management background; Erin is an analyst and user experience expert. We need to bring on a full-time technical lead and a front-end designer. I can't do either my CEO (sales! research! business development!) or web development jobs justice, and Erin can't do her user experience or front-end jobs justice. We also need to have redundancy on our staff, so if one of us is sick or out doing sales work, the company can continue to be productive. As soon as you start talking about building a real team, those numbers explode.

I don't believe it's possible to start a consumer startup as a full-time endeavor without significant investment. Unlike businesses, only a tiny minority of consumer users are willing to pay money. You need to have enough runway (the time left in your company before it runs out of money) to reach a mass-market audience, and then make sure you're either solving a problem that they are willing to pay for a solution to. Because it's so hard to get money from consumers, these businesses often make their money through advertising: reaching targeted, engaged audiences is absolutely a problem that advertisers will pay for a solution to.

Enterprise startups potentially require less investment, but the sales cycle - the time it takes to sell to an individual customer - is potentially much longer, and the total cost to acquire a single customer is much higher. You need to have enough money in the bank to make this work; investment is a useful vehicle to bring your company to the next stage of its development.

Investors protect their money by minimizing risk. In this context, open source is a liability: remember the free as in beer problem? By giving away the portion of your product that captures value, you're essentially devaluing your business to zero. Why would anybody invest in that? I'm sincerely grateful that Matter did invest in our team. In return, the least we can do is be a good steward of investor value.

That $240,000? It's a baseline. Biz was completely right: you need to hold back the thing that makes you valuable.

Feedback is a gift - and so is open source.

When they work well, open source communities are amazing things: collaborative groups of disparate people all agreeing to make software together for use by the commons. As a methodology, it's beautiful, and can showcase the best of humanity.

When you're building a product for sale, it's important that you've identified a problem that people will pay money to have solved for them, and that you're solving it well. That means talking to a lot of people, and both making and iterating a lot of rough prototypes. Your product has to be compelling, well-made and scalable. As it's concisely described in design thinking circles, you need to constantly be testing its desirability, feasibility and viability.

When your product is open source, you'll get a lot of feedback from the community. This is important to take on board, and the community is a hugely valuable part of your ecosystem - but at the same time, it's unlikely that open source community members are customers. It's possible that they're users; it's also possible that they're open source enthusiasts who are just happy to see another project join the movement.

Open source projects, as a whole, have famously bad usability. That's because their feedback loop is constrained to other developers. One recent example of this disconnect is a heated debate about using Slack vs Internet Relay Chat. To non-technical users, IRC is arcane and unfriendly (which also accurately describes many of the discussions that take place there), yet many open source maintainers couldn't understand the problem.

When you're building a compelling product, the license should be irrelevant. It should be compelling whether it's completely closed or released under the GPL: the license is how you distribute the product, not something that's inherent to the product itself.

Unfortunately, in the case of Known, I think a lot of people liked it because it was free and open source. This was a bad signal - and certainly not one that will lead to paying customers and a thriving business. (It's worth saying here that a consistent voice of real support has been the indie web community, alongside companies like Reclaim Hosting, which legitimately wants to see us succeed.)

I'm not Donald Trump, but ...

The biggest surprise I've had since starting Known is the amount of feedback complaining that we're trying to make money with it. Usually this comes with some kind of a complaint about startups and capitalism.

If you know me, you'll know that my politics err on the liberal side of liberal; Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are the US politicians who best describe the country I want to live in. I'm hardly a hardcore conservative capitalist. Nonetheless, I was taken aback to discover that we'd accidentally joined an anti-capitalist movement: we've been very open about being a business since the day we announced our existence.

In fact, I really wanted to show that it was possible to create a profitable, thriving business creating respectful software that gives users full control of their data. I think it's important.

Here are some real things I've heard about making money from open source:

- We should have a universal basic income so people won't have to worry about how they'll make money.

A universal basic income is not money from the sky; it's a proven way to create a real safety net, but it does rely on taxation. It doesn't work if everyone relies on a basic income, and the idea that you should have to live at the lowest possible income if you're going to build respectful software is both ridiculous and kind of offensive. Welfare is important, but not as a way to pay for open source software.

- We should be striving to build a post-money society.

I mean, to be fair, I'm a Star Trek fan too.

- We should just build software for the love of it and not worry about making money.

Most egregiously, we've heard this from people who literally take our free product and sell services around it.

All of these are obviously detatched from reality.

This culture of anti-capitalism in open source is actively harmful. It's a reason why so few women (1.5%!) participate in open source projects, for example, and why people in disadvantaged communities are underrepresented. Having the ability to work on a project for free represents enormous privilege. At its best, open source can be a way for people to contribute to a global commons and freely exchange ideas; at its worst, it's exploitative and exclusionary.

It's devalued our time. I get personal requests on all channels on a daily basis - email, Twitter, Facebook, even unsolicited phone calls - asking for free help. (I no longer give free personal help, except on the mailing list, where it can be used to grow a commons of support information that everyone can use.) Sometimes these calls for free help come from people who are making money from our labor.

Open source doesn't need folk songs. It needs a way to fairly compensate the people who participate in it. I'm not at all against anti-capitalism - but it sure is hard to build a business on it.

But aren't there a lot of profitable open source businesses?

No.

We've most often been compared to WordPress, which powers over 23% of the web. Automattic is valued at over $1.1bn, has a huge team worldwide, and is widely held as the poster child for open source businesses.

In reality, the WordPress open source project is held by a non-profit foundation. Automattic concentrates solely on hosted services.

Ghost, another project we've been compared to, is a non-profit entity in its entirety. It made a lot of its money by crowdfunding as a WordPress plugin, before switching to becoming a node.js project. This technical change made it much harder to install, making their paid, hosted services an easy choice.

Ind.ie hasn't really launched Heartbeat, their distributed social network, but their project is significantly better-funded than Known. This is partially because they crowdfunded as a smartphone, before choosing to shift their attention to a more focused problem.

Mozilla has a long history that stems from Netscape. Their success is not something that a new entrant to the market could replicate.

Red Hat is held up as a model open source business: its current market cap is $14.8bn, or roughly 2.8% of a Google. It provides professional services and support licensing around its Linux distributions.

Infrastructure is a more profitable place for open source to thrive: MongoDB, CoreOS and Docker are all examples of well-funded open source startups. Each one sells better support, trustability and reliability - which makes sense to pay for if you're building a business on top of their technologies.

For these businesses, open source allows them to build a bigger market for their products, which they can then capitalize on. It's a smart strategy that has very little to do with freedom, and everything to do with growth.

What about other funding methods?

BountySource, the crowdfunding platform for open source projects, is one oft-mentioned funding method. It's actually a pretty great idea, that I think will wonderfully for hobbyists, and will encourage developers on distributed projects to work on smaller bugs and features. I don't foresee it covering our costs.

Similarly, Patreon works very well for personal projects, and is redefining how some artists make their money.

We currently make a significant portion of our income through professional services, but this isn't sustainable for a number of reasons. As Tomasz Tunguz at Redpoint Ventures pointed out earlier this year in this excellent analysis:

The data suggests that customers are willing to pay 20%+ margins on price points of greater than $200,000. Less than that price point, the data shows it to be difficult to operate a professional services team at better than breakeven.

When you consider all of the overheads inherent to running a company, you would actually make more money just being a freelance developer. Professional services jobs are often one-offs, and while they sometimes lead to contracts, it can be an equal effort to go find the next one. It's not a great way to grow.

That also negates the common argument about making money by providing tertiary services like support and customization. These strategies add more risk to the business, and don't cumulatively add value. At lower price points, it's not even a lifestyle business: it's hand to mouth.

What's next?

None of this should be a downer. I want to open a real conversation about making money sustainably with respectful software. Between Elgg and Known, I've spent the majority of my career working on these issues. I think they're solvable, and I think the result will be a better software ecosystem.

Known isn't at all going away, and we continue to release new versions every single month. We're evaluating the services we provide around it, but we love how the community has rallied around it, and we love how it's being used. We expect it to live and breathe for a long time.

However, we're learning from companies like Automattic, and non-profits like the WordPress Foundation. We're thinking hard about how the project is supported. And it should go without saying that we're committed to building a valuable, growing business.

There's a strong movement around creating alternatives to software that tracks and spies on us. I think that's a fantastic thing. Building software is about empowering people to do things they previously couldn't. But a part of building empowering tools is to make sure they can be provided sustainably. If you're doing something good, you need to be able to keep doing it - and whether you like it or not, that means money.

We need to have a stronger conversation about money in open source, and about building healthy businesses on respectful software.

Conclusions

As either Milton Friedman or Alfred P. Sloan said: "the business of business is business". Build a healthy business; don't be led by ideology. You're not helping build a more open world if you're showing that being open is unsustainable or detrimental; show that you can do well.

And when you succeed, use the fruits of your labor to do good.

We'll be here, cheering for you.

I wrote a follow-up to this post: why we built Known.

Share this post

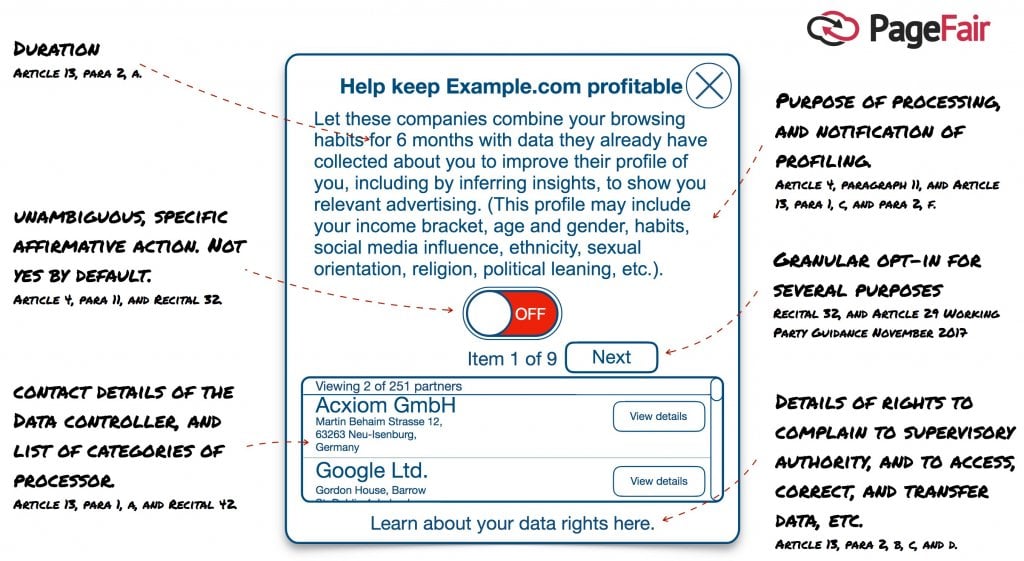

Share this post The sample wireframes they've come up with are hilariously onerous, and Europeans will have to opt in on every single site where data is collected. The result will be that almost nobody agrees to give their information universally across all sites, which is the current status quo (because right now, nobody's being asked for anything).

The sample wireframes they've come up with are hilariously onerous, and Europeans will have to opt in on every single site where data is collected. The result will be that almost nobody agrees to give their information universally across all sites, which is the current status quo (because right now, nobody's being asked for anything). Working with

Working with

If that's what you have, Matter doesn't end at Demo Day. This last Friday,

If that's what you have, Matter doesn't end at Demo Day. This last Friday,

Rather than taking a retrospective look back at 2015, I think it's interesting to look ahead think about what I want my themes for the next year to be, both personally and professional. Here's mine; I'd love to see yours.

Rather than taking a retrospective look back at 2015, I think it's interesting to look ahead think about what I want my themes for the next year to be, both personally and professional. Here's mine; I'd love to see yours.