This is my monthly roundup of the books, articles, and streaming media I found interesting. Here's my list for September, 2021.

Apps + Websites

Ambient Chaos. Finally, an ambient noise generator for the rest of us. I recommend zombie invasion + barnyard animals + church bells + lo-fi beats.

You feel like shit. “This is meant to be an interactive flow chart for people who struggle with self care, executive dysfunction, and/or who have trouble reading internal signals. It’s designed to take as much of the weight off of you as possible, so each decision is very easy and doesn’t require much judgment.” Nicely done.

Feeds Mage. This is wonderful: a way to extract blog feeds from your Twitter followers. I’ve been looking for something like this for some time.

Books

Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story, by Ursula K. Le Guin. Simple, effective lessons on writing, delivered with wit and insight by a master of her craft. Absolutely perfect. I’ll be coming back to this for the rest of my life.

Ms. Marvel Vol. 2: Generation Why, by G. Willow Wilson. Not quite as refreshing as the first volume - this one brings in both the X-Men and the Inhumans, dragging it into the Marvel universe more completely. But it’s still a ton of fun. Can’t wait to read the next one, and to see the series.

All Systems Red, by Martha Wells. An engagingly-written novella with a comic book sensibility. Fun: I would have absolutely devoured this when I was younger.

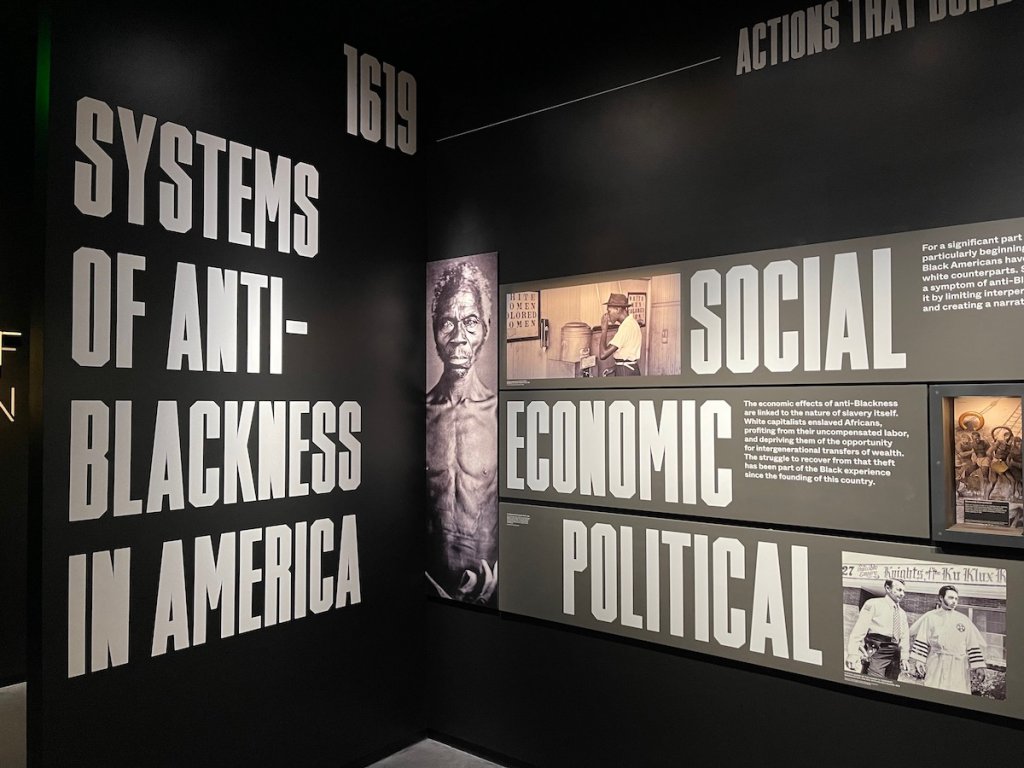

Across the Tracks: Remembering Greenwood, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre, by Alverne Ball, Stacey Robinson, and Reynaldo Anderson. A short but meaningful graphic introduction to the Tulsa Race Massacre and the historical precedents leading up to it. It’s a story that more people should be aware of, and one that continues to echo today. This was a great start that left me wanting to dive in deeper.

Streaming

Django Moves to Portland - "Excellent Growbag" - Live on Shady Pines Radio. My sister Hannah wrote this song about death and decomposition, which is so lovely that my mother requested that it be performed at her memorial (which it was). Here she’s playing it as part of Shady Pines Radio’s Nocturnal Submissions.

Lil Nas X - Jolene (Dolly Parton Cover) in the Live Lounge. Just brilliant.

Notable Articles

Business

The startup where meetings are optional and Slack is forbidden. “Apart from the regular all-hands, individual contributors at Convictional only have a weekly one-on-one meeting with their manager, and like other asynchronous or async-first companies such as GitLab, Zapier and Twitter, the company relies heavily on email and document-sharing to communicate. But outside of Convictional, it’s hard to find another tech company that doesn’t use any chat or messaging platform at all.” This sounds quite lovely.

She’s the Investor Guru for Online Creators. “Hank Green, 41, a top creator on YouTube and TikTok, said he often tossed ideas back and forth with her by phone. Markian Benhamou, 23, a YouTuber with over 1.4 million subscribers, credited her with understanding what creators go through. Marina Mogilko, 31, a YouTube creator in Los Altos, Calif., said Ms. Jin “started the whole creator economy movement in Silicon Valley.””

The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. “Our results show that firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network of workers to become more static and siloed, with fewer bridges between disparate parts. Furthermore, there was a decrease in synchronous communication and an increase in asynchronous communication. Together, these effects may make it harder for employees to acquire and share new information across the network.” So, how can we build new tools and processes to overcome these effects?

We are benefitting hugely from Brexit, says Estonia’s prime minister. ″“We have seen more than 4,000 British companies coming to Estonia,” Kallas continued, explaining that the UK companies’ main reasons were access to the EU, the country’s tax system, as well as Estonia’s flourishing tech scene and digital infrastructure.” Brexit was such a stupid own goal, and systems like Estonia’s make a ton of sense.

The trouble with ERGs. “An ERG wants to make all these really concrete changes often at a workplace but has no power to do that [...] They might have some funding or the ear of an executive, which we did at Uber, but ultimately it kind of relies on the good faith of an executive to work on whatever changes you want. ERGs kind of passively work against the idea of a union in that they’re a way for you to kind of spend your energy without it turning into anything, which I’m really sad about, but that’s what I’ve found in my experience.”

Returning to the Office and the Future of Work. “Wage labor can harm us in subtle and insidious ways, too. The American ideal of a good life earned through work is “disciplinary,” according to the Marxist feminist political philosopher Kathi Weeks, a professor at Duke and often-cited critic of the modern work ethic. “It constructs docile subjects,” she wrote in her 2011 book, “The Problem With Work.” Day to day, that means we feel pressure to become the people our bosses, colleagues, clients and customers want us to be. When that pressure conflicts with our human needs and well-being, we can fall into burnout and despair.”

How Lessonly, Bumble and HubSpot fight burnout. “In early May, the founder of Lessonly, a company that makes training software, sent out a companywide email issuing a mandate to all employees. But it wasn’t the sort of mandate employees around the world have been receiving related to vaccines and masks. This mandate required that every worker take an entire week off in July.” Next up, sabbaticals?

What We Actually Want Out Of Management. “Management is problematic because it is frequently used as a reward - a chance to make more money, but also exert power and control over people. Becoming a manager is a means of escaping the doldrums of the worker and allows you to start being the pusher rather than the pushed. Managers are often not measured on their team’s success or failures, or if they are, they are allowed to escape blame by claiming an underling failed them or gain accolades by claiming that they did the work somebody else did. The cultural disconnect of management from labor is the core problem - and, indeed, a lack of understanding of what leadership and management actually means.”

Inclusive meetings: encouraging collaboration from all. A really clear, well-written guide to running meetings well from the Co-op.

Crypto

Loot is a viral social network that looks like nothing you've ever seen. “At this point I feel it necessary to point out that there are no adventurers in Loot. There is no game in Loot. There are just items, and pictures of those items, and tens of millions of dollars betting that it will all somehow turn into something much more. As one tweet put it: “Loot is NFT improv.” [...] “At the end of the day, these are just items on a list,” Hofmann said.”

Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible? “We’ll explain how that works in a minute. But first, consider this: The process of creating Bitcoin to spend or trade consumes around 91 terawatt-hours of electricity annually, more than is used by Finland, a nation of about 5.5 million.” Or, seven Googles.

China says all cryptocurrency-related transactions are illegal and must be banned. “The central bank said cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin and Tether, cannot be circulated in the market as they are not fiat currency. The surge in usage of cryptocurrencies has disrupted “economic and financial order,” and prompted a proliferation of “money laundering, illegal fund-raising, fraud, pyramid schemes and other illegal and criminal activities,” it said.” Cue a minor crypto crash. But honestly: I expect that other countries may follow and create a dividing line between places that allow these currencies and those that don’t.

Why not replace bitcoin’s proof of work with proof of astrophysics. “Caveat: I clearly don’t know what I’m talking about. BUT could we invent new underpinnings of cryptocurrency that pump out social good, rather than pumping out carbon? It would be good to assemble a committee of smart people to figure that out.” I agree. I also worry about the opposite: I’ve been trying to write a story that involves a coin powered by proof of manual labor.

Culture

Abba reunite for Voyage, first new album in 40 years. Mamma mia.

'A Loveable Anarchist': The Oral History of Mr Blobby. “Now a cultural signifier of the 90s, Mr Blobby burst onto our screens in October 1992 as a character on the BBC’s Saturday night show Noel’s House Party. Hosted by Noel Edmonds, it had a “Gotcha” segment where they would prank celebrities. That’s where Mr Blobby came in. He was only supposed to last one series. But somehow, that’s not what happened.” If you’re new to Blobby, don’t miss the single, which may genuinely be the worst song ever recorded.

I found the largest truffle in the world. “I weighed the truffle straight away and knew I had something special on my hands. It weighed 1,310g. In the morning I spoke with Guinness World Records, who confirmed that it was the biggest truffle ever recorded. I could have sold it for €1m and made my fortune, but I knew instantly that I didn’t want to do that. It’s great to be rich, but I felt the truffle could have more impact if it was shared. The truffle was found in Istria and should be consumed here, not sold to a rich person abroad.” A lovely story.

Solarpunk Is Not About Pretty Aesthetics. It's About the End of Capitalism. “Solarpunk took inspiration from the Cyberpunk and Steampunk aesthetics that came before it—take the lush paradises of Studio Ghibli films with just a few more solar panels. Cyberpunk uses science fiction to explore our anxieties in the rapidly developing technical age, while Steampunk is nostalgic for the aesthetics of the industrial revolution. But unlike these dystopian and mechanical universes, Solarpunk is a more optimistic, regenerative vision of the future.” I’m all in.

One Woman’s Mission to Rewrite Nazi History on Wikipedia. “Similar battles over how to remember the past have been raging across society. Do we let the old bronze statues stand in our boulevards, or do we put them in a museum someplace, or do we melt them down? Can there be a “hero” who fought for a morally rotten cause? Are qualities like valor and self-sacrifice and tactical brilliance worth admiring anywhere they occur, even if, say, racial supremacism is there too? Some choose to take to the streets. Coffman fights on the terrain most familiar to her, with the weapons she knows best. Not that she would put it that way; she’s not big on war metaphors.”

A novel is born. I’m obsessed with this kind of thing: an author self-publishing across various media using the internet as a kind of canvas. So obsessed that I really want to try it myself.

Russell T Davies to return as Doctor Who showrunner. Wowsers! RTD revived the best show ever made and laid the blueprint. I’m excited.

Media

Re-thinking Academic Publishing: The Promise of Platform Cooperativism. “Or could we imagine a future where scholars are the ones at the helm of the scholarly publishing ecosystem? In this contribution, we propose to do just that: imagine a different — fairer, more economically sustainable, and inclusive — approach to open access. However, to do that, we need to think not only outside the scope of existing business and publishing models but also the existing organisational models.”

Journalist William Huie Concealed Lynchers in Emmett Till Case. “As Dave Tell points out in his book, “Remembering Emmett Till,” Huie needed releases from the murderers to indemnify Look magazine from litigation. But he couldn’t get four. He could only get two. So, he made his story fit his resources. He shrank the kidnapping and murder party to two and moved the murder scene as a consequence. So, instead of telling readers the truth—that Till’s lynchers killed him in a barn on a plantation run by Leslie Milam, a member of the killing party whom Huie concealed—he claimed J.W. Milam and Bryant beat Till near J.W. Milam’s home and shot him to death on the Tallahatchie River’s bank.”

Lyra McKee: four men arrested over killing of journalist in Derry. “The four men, aged 19, 20, 21 and 33, were arrested under the Terrorism Act 2006 on Wednesday morning. They were in the Derry area, and are now being questioned at Musgrave police station in Belfast.” Lyra’s death was a loss for the world.

How one coder became Indonesia’s misinformation guru. “To the overwhelming majority of observers, Fahmi successfully treads the line between the interests of entities who could be either his clients or his targets. Drone Emprit is one of a kind. With it, Fahmi has established credibility as a misinformation authority in a noisy landscape.”

Ministers plan legal requirement for broadcasters to make 'clearly British' shows like Only Fools and Horses. “Fleabag, Derry Girls and Only Fools and Horses were cited as the kind of “distinctively British” programmes that would meet the obligation. Ofcom will be asked to draw up a workable definition of the concept.” I’m not positive, but this might be the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard?

Sun-Times, WBEZ parent company to explore historic partnership to create country’s largest local nonprofit news service. “The Chicago Sun-Times and the parent company of public radio station WBEZ will explore a potentially historic partnership under a non-binding letter of intent that could create one of the largest local nonprofit news organizations in the country.” This makes a ton of sense - and doesn’t it make a nice change for consolidation to build bigger and better non-profit news orgs rather than some kind of private equity acquisition?

What I learned from a year on Substack. “The result is a job that feels more durable, and sustainable, than any other employment I’ve had. In the past, to lose my job might require only a bad quarter in the ad market, the loss of an ally in upper management, or the takeover of my company by some indifferent telecom company. Today, I can really only lose my job if thousands of people decide independently to “fire” me. As a result, I’ve never felt more empowered to cover the issues I find most meaningful: the fraught, unpredictable collisions between big tech platforms and the world around them.”

Politics

Newly formed White House council to promote competition across US economy to hold first meeting. “In July, Biden signed a sweeping executive order to promote competition in the US economy, parts of which target a key business strategy used by Silicon Valley companies. The wide-ranging order aims to lower prescription drug prices, ban or limit non-compete agreements that the White House says impede economic mobility and cracks down on Big Tech and internet service providers, among several other provisions.”

Science

Coronavirus Ventilation: A New Way to Think About Air. “COVID-19 does not kill as high a proportion of its victims as cholera did in the 19th century. But it has claimed well over 600,000 lives in the U.S. Even a typical flu season kills 12,000 to 61,000 people every year. Are these emergencies? If so, what would it take for us, collectively, to treat them as such? The pandemic has made clear that Americans do not agree on how far they are willing to go to suppress the coronavirus. If we can’t get people to accept vaccines and wear masks in a pandemic, how do we get the money and the will to rehaul all our ventilation systems?” But it’s not just about Covid - better indoor air quality could help in lots of ways.

Barnyard breakthrough: Researchers successfully potty train cows. ″“The calves’ rate of learning is within the range seen with 2- to 4-year-old children, and faster than for many children,” Matthews says. The waste, Langbein adds, could be moved to a storage tank, used for fertilizer, or even sampled to monitor the health of individual cows.”

Blood Concrete Could Be Used to Build Dwellings on Mars. “You may not be able to get blood from stone. But now, getting stone from blood is a real possibility… At least on Mars. New research published in Materials Today Bio suggests an unlikely source for building materials on Mars: astronauts’ blood.”

Harvard study challenges gender’s role in COVID-19 death rates. “Researchers agree more men are dying of COVID-19. But a new paper challenges whether biology is to blame.” Men are more likely to be at risk due to their context and profession (and sometimes, attitude).

The Kidney Project successfully tests a prototype bioartificial kidney. “The Kidney Project’s artificial kidney will not only replicate the high quality of life seen in kidney transplant recipients—the “gold standard” of kidney disease treatment, according to Roy—but also spare them from needing to take immunosuppressants.” This is a game-changer. Artificial organs could improve the quality of life of every transplant patient, which is progress that I care about a great deal.

U.S. declares more than 20 species extinct after exhaustive searches. “The Fish and Wildlife Service announced Wednesday that 22 animals and one plant native to the United States are now extinct and should be removed from the endangered species list after exhausting efforts to find evidence that they are still alive.”

Society

Oh My Fucking God, Get the Fucking Vaccine Already, You Fucking Fucks. It’s not going to affect anyone’s opinion, but I identify with the frustration: “You think vaccines don’t fucking work? Oh, fuck off into the trash, you attention-seeking fuckworm-faced shitbutt. This isn’t even a point worth discussing, you fuck-o-rama fuck-stival of ignorance. Vaccines got rid of smallpox and polio and all the other disgusting diseases that used to kill off little fucks like you en masse. Your relatives got fucking vaccinated and let you live, and now here you are signing up to be killed by a fucking disease against which there is a ninety-nine-percent effective vaccine. You fucking moron. Go in the fucking ocean and fuck a piranha. Fuck. Fuck that. Fuck you. Get vaccinated.”

We’ve Forgotten the Meaning of Labor Day. “American society has confused the worth of life with the value of cash, and the pandemic has made us pay for our mistake. It is time that makes a society flourish and life worth living. Time offers us the opportunity to share and learn and laugh and grow; it gives us the space to process and heal and renew. Time is the necessary ingredient in developing any skill, sharpening any talent, building any success, crafting any joy—and for too many people in this country, it is bought too cheaply.”

Experience: a stranger secretly lived in my home. “For years, the experience haunted me. When I was at home alone, I felt as if I was being watched. I lived somewhere else with an attic hatch and asked the landlord to put a lock on the outside.”

The Jan. 6 Riot Proves the Sept. 11 Era Isn't Over. ″“I am not a terrorist,” insisted Adam Newbold, a former Navy SEAL who posted that he had breached the Capitol. The war on terror had accustomed him to think that he could not be one by definition. But the most durable terrorism in this country is white people’s terrorism. A war cannot defeat it. Persistent political struggle can.”

Fear and Loathing in America. “The towers are gone now, reduced to bloody rubble, along with all hopes for Peace in Our Time, in the United States or any other country. Make no mistake about it: We are At War now -- with somebody -- and we will stay At War with that mysterious Enemy for the rest of our lives.” Hunter S Thompson’s column about 9/11, written just 24 hours after the attacks. And it’s unfortunately completely spot on about what the next 20 years would be like.

Judith Butler calls out transphobia as “one of the dominant strains of fascism in our times”. ″“The anti-gender ideology is one of the dominant strains of fascism in our times,” Butler said, referring to everyone who believes that sex is “biological and real or that sex is divinely ordained,” including TERFs like J.K. Rowling, fascists like Tucker Carlson, and religious conservatives like Rep. Greg Steube (R-FL). Their definition of the “anti-gender ideology movement” also includes anti-gay activists like opponents of marriage equality and anti-feminists who want to force women to follow traditional gender roles.” Notably, this section of the interview was subsequently censored by The Guardian.

Here's why California has the lowest COVID rate in the nation. ““If the small inconvenience of wearing a mask could protect my neighbor, I wear one with a smile,” he said. “Similarly, if the science, my own self-interest and the protection of my neighbors all are promoted by getting a vaccine, I’m happy to join my neighbors in line.”” Thank you, California.

He found forgotten letters from the '70s in his attic. Turns out they were missives from the Unabomber. “When it hit me that my correspondent was the same Ted Kaczynski who’d killed three people he’d never met, I felt a shiver of recollection of the fear that prevailed in the Bay Area in the 1970s, during the heyday of serial killers such as the Zodiac, Zebra, Santa Rosa Hitchhiker and Golden State. I was also, to be honest, thankful I hadn’t been rude to him.”

First ever census data on LGBTQ+ people indicates deep disparities. “According to the data, which captures results from July 21 to September 13, LGBTQ+ people often reported being more likely than non-LGBTQ+ people to have lost employment, not have enough to eat, be at elevated risk of eviction or foreclosure, and face difficulty paying for basic household expenses, according to the census’ Household Pulse Survey, a report that measures how Americans are faring on key economic markers during the pandemic.”

Prison Destroyed Video Proof of Guards Torturing Anti-Fascist, Lawyers Say. “According to new motions to dismiss filed by the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC), a legal nonprofit, BOP prison staff attacked King after leading him into a small, off-camera storage closet, then deleted video evidence, and may have misrepresented facts about the incident to the FBI. King’s attorneys also claim officers tied him to a four-point restraint device for approximately five hours, and then proceeded to interrogate him despite his asserting his constitutional right to counsel.”

Technology

Apple delays plan to scan iPhones for child exploitation images. ″“Last month we announced plans for features intended to help protect children from predators who use communication tools to recruit and exploit them, and limit the spread of Child Sexual Abuse Material,” the company said in a statement. “Based on feedback from customers, advocacy groups, researchers and others, we have decided to take additional time over the coming months to collect input and make improvements before releasing these critically important child safety features.””

How Docker broke in half. “With the benefit of hindsight, Hykes believes that Docker should have spent less time shipping products and more time listening to customers. “I would have held off rushing to scale a commercial product and invested more in collecting insight from our community and building a team dedicated to understanding their commercial needs,” Hykes said. “We had a window in 2014, which was an inflection point and we felt like we couldn’t wait, but I think we had the luxury of waiting more than we realized.””

Someone could be tracking you through your headphones. “On several occasions, student and IT enthusiast Bjørn Martin Hegnes has been carrying equipment for listening in on Bluetooth and WiFi messages for an academic project. His goal was to investigate how many of us can be tracked in secret without even noticing.” Older Bluetooth devices maintain static MAC addresses which allow you to be tracked over time.

Releasing our Digital Vaccine Record code on GitHub. This is wonderful! California has released its digital vaccine record code as open source, allowing every state - and beyond - to operate their own standards-compliant, privacy-preserving record. More of this approach, please.

Facebook sent flawed data to misinformation researchers. ““A lot of concern was initially voiced about whether we should trust that Facebook was giving Social Science One researchers good data,” Mr. Buntain said. “Now we know that we shouldn’t have trusted Facebook so much and should have demanded more effort to show validity in the data.””

Digital exposure tools: Design for privacy, efficacy, and equity. “Exposure-notification apps are predicated on the assumption that if someone is informed of exposure, they will follow instructions to isolate. Such an expectation fails to take into account that isolation—and sometimes even seeking care when ill—is much harder for some populations than others. If apps are to work for all, and not make this worse for disadvantaged populations, there needs to be basic social infrastructure that supports testing, contact tracing, and isolation.”

Facebook Says Its Rules Apply to All. Company Documents Reveal a Secret Elite That’s Exempt. “In private, the company has built a system that has exempted high-profile users from some or all of its rules, according to company documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.”

Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show. ″“Social comparison is worse on Instagram,” states Facebook’s deep dive into teen girl body-image issues in 2020, noting that TikTok, a short-video app, is grounded in performance, while users on Snapchat, a rival photo and video-sharing app, are sheltered by jokey filters that “keep the focus on the face.” In contrast, Instagram focuses heavily on the body and lifestyle.”

The Very First Webcam Was Invented to Keep an Eye on a Coffee Pot at Cambridge University. I don’t feel old, generally, except when I read pieces like this. I remember accessing this webcam like it was yesterday ...

Home computing pioneer Sir Clive Sinclair dies aged 81. “His first home computer, the ZX80, named after the year it appeared, revolutionised the market, although it was a far cry from today’s models. At £79.95 in kit form and £99.95 assembled, it was about one-fifth of the price of other home computers at the time. It sold 50,000, units while its successor, the ZX81, which replaced it, cost £69.95 and sold 250,000.” The ZX81 was my formative first computer. Rest in peace, sir.

Troll farms reached 140 million Americans a month on Facebook before 2020 election. “The report reveals the alarming state of affairs in which Facebook leadership left the platform for years, despite repeated public promises to aggressively tackle foreign-based election interference. MIT Technology Review is making the full report available, with employee names redacted, because it is in the public interest.”

Apple and Google Remove ‘Navalny’ Voting App in Russia. “Google removed the app Friday morning after the Russian authorities issued a direct threat of criminal prosecution against the company’s staff in the country, naming specific individuals, according to a person familiar with the company’s decision. The move comes one day after a Russian lawmaker raised the prospect of retribution against employees of the two technology companies, saying they would be “punished.”” This wouldn’t be an issue if the app store wasn’t hopelessly centralized.

Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley’s Pursuit of Power. “The specifics of the discussion were secret — but, as I report in my book, Thiel later told a confidant that Zuckerberg came to an understanding with Kushner during the meal. Facebook, he promised, would avoid fact-checking political speech — thus allowing the Trump campaign to claim whatever it wanted. In return the Trump administration would lay off on any heavy-handed regulations. Facebook had long seen itself as a government unto itself; now, thanks to the understanding brokered by Thiel, the site would push what the Thiel confidant called “state-sanctioned conservatism.”” Yikes.

Kids who grew up with search engines could change STEM education forever. “Gradually, Garland came to the same realization that many of her fellow educators have reached in the past four years: the concept of file folders and directories, essential to previous generations’ understanding of computers, is gibberish to many modern students.”

One to charge them all: EU demands single plug for phones. “Under the proposed law, which must still be scrutinized and approved by the European Parliament, phones, tablets, digital cameras, handheld video game consoles, headsets and headphones sold in the European Union would all have to come with USB-C charging ports. Earbuds, smartwatches and fitness trackers aren’t included.” I’m in favor of this kind of regulation - consider standardized mains power sockets, for example. As long as it doesn’t lock in USB-C forever.

What’s Missing from the Infrastructure Bill’s $65 Billion Broadband Plan? “The infrastructure bill, if passed as is, will require new broadband projects to provide 100 Mbps of download speed and 20 Mbps of upload speed. But the infrastructure bill falls short of providing what some advocates say is necessary: “symmetrical” upload and download speeds.”

Share this post

Share this post