As regular readers know, I care a lot about growing the open social web: the rapidly-growing decentralized network of interoperable social platforms that includes Mastodon, Threads, Ghost, Flipboard, and many other platforms, both emerging and established. This is for a few reasons, including but not limited to:

Support for strong communities

- Support for niche interests and diversity: Smaller, independent communities can flourish without the pressure to appeal to mass audiences, leading to richer, more diverse conversations and interactions. But these aren’t silos: any member from one community can easily follow someone from any other.

- Community-driven moderation: Instead of top-down moderation, communities set their own rules and guidelines, which can lead to healthier and more relevant interactions. Community health isn’t subject to a single corporation’s policies and motivations.

Better developer experience

- An easier way to build social apps: Shared libraries, tools and protocols let developers get started faster. And developers no longer have to worry about their social products feeling empty: every new product can plug into communities of millions of people.

- Developer stability: Developers don’t need to ask anyone for permission to build on open social web protocols. Nobody will suddenly turn off the open social web and charge developers to access it: just like the web itself, it’s open and permissionless, forever. The result is a less risky playing field for new entrants.

Respect for users

- Decentralized governance: Users have more control over their data, identity, and interactions, without reliance on a single corporation or platform.

- Freedom from corporate algorithms: No algorithm-driven feeds prioritize ads or engagement-maximizing content, allowing for more authentic and community-driven interaction (and significantly less election interference, for example).

- Data ownership and portability: Users have greater control over their data and are not at the mercy of corporate interests. The open social web has the potential to connect every social platform, allowing anyone to be in conversation. And users can move from provider to provider at any time without losing their communities.

- Reduced surveillance: Federated systems are often less focused on advertising and surveillance-based business models, reducing targeted ads and invasive data collection.

- A more ethical ecosystem: It’s far easier for developers to build ethical apps that don’t hold user data hostage.

I’d love to be more involved in helping it grow. Here are some ways I’ve thought about doing that. As always, I’d love to hear what you think.

Acting as an advocate between publishers and vendors.

Status: I’m already doing this informally.

Open social web vendors like Mastodon seem to want to understand the needs of news publishers; there are already lots of advantages for news publishers who join the open social web. There’s some need for a go-between to help both groups understand each other.

Publishers need to prove that there’s return on investment on getting involved in any social platform. Mastodon in particular has some analytics-hostile features, including preventing linked websites from knowing where traffic is coming from, and stripping the utm tags that audience teams use to analyze traffic. There’s also no great analytics dashboard and little integration with professional social media tools.

Meanwhile, the open social web already has a highly engaged, intelligent, action-oriented community of early adopters who care about the world around them and are willing to back news publishers they think are doing good work. I’ve done work to prove this, and have found that publishers can easily get more meaningful engagement (subscriptions, donations) on the open social web than on all closed social networks combined. That’s a huge advantage.

But both groups need to collaborate — and in the case of publishers, need to want to collaborate. There’s certainly work to do here.

Providing tertiary services.

Status: I built ShareOpenly, but there’s much more work to do.

There are a lot of ways a service provider could add value to the open social web.

Automattic, the commercial company behind WordPress, got its start by providing anti-spam services through a tool called Akismet. Automattic itself is unfortunately not a wonderful example to point to at this moment in time, but the model stands: take an open source product and make it more useful through add-ons.

There’s absolutely the need for anti-spam and moderation services on the open social web (which are already provided by Independent Federated Trust And Safety, which is a group that deserves to be better-funded).

My tiny contribution so far is ShareOpenly, a site that provides “share to …” buttons for websites that are inclusive of Mastodon and other Fediverse platforms. A few sites, like my own blog and Tedium, include ShareOpenly links on posts, and it’s been used to share to hundreds of Mastodon instances. (I don’t track links shared at all, so don’t have stats about that.) But, of course, it could be a lot bigger.

I think there’s potential in anti-spam services in particular: unlike trust and safety, they can largely be automated, and there’s a proven model with Akismet.

Rebuilding Known to support the Fediverse — or contributing to an existing Fediverse platform.

Status: I just need more time.

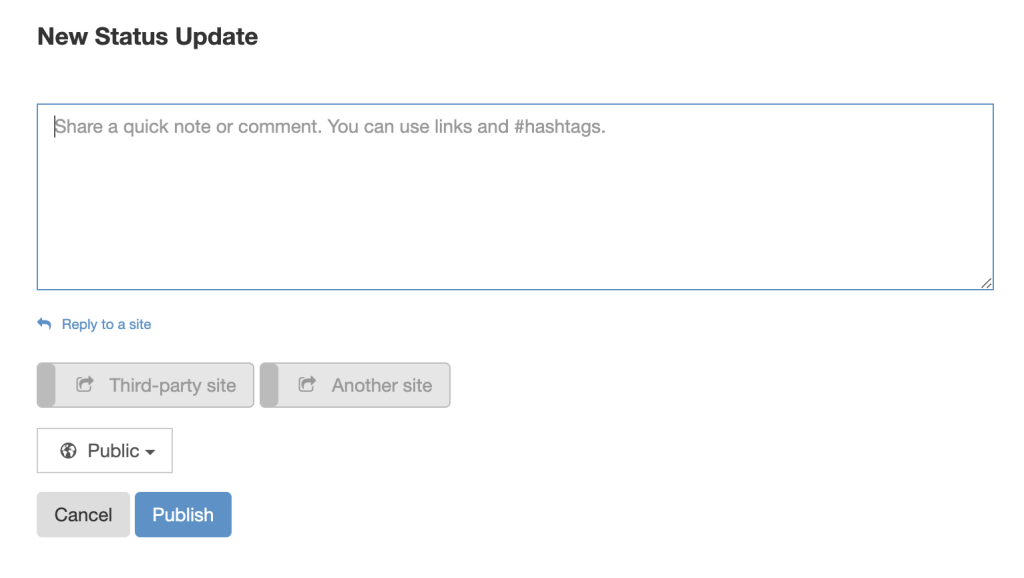

My publishing platform Known could be rewritten to have a new, faster, cleaner architecture that is Fediverse-first.

It’s not clear to me what the sustainability model is here: how can I make sure I continue to have the time and resources to work on it? But I do think there’s a lot of potential for it to be useful — particularly for individual bloggers and smaller publishers — once it was built.

And of course, there are many other open source Fediverse platforms (like Mastodon) that always need extra hands. The question remains: how can I find the time and resources to be able to make those contributions?

(I’ve already tried: funding as a startup, consultancy services, donations, and a paid hosting service. If you’ve got other ideas, I’d love to hear them!)

An API engine for the Fediverse

Status: idea only, but validated with both experts and potential customers. Would need to be funded.

ActivityPub, the underlying protocol underneath the Fediverse, can sometimes be hard to implement. Unlike many web apps, you often need to set up asynchronous queues and process data in potentially expensive ways when both publishing and reading data from other instances.

So why not abstract all of that away? Here smaller communities and experimental developers can rely on shared infrastructure that handles inboxes and queues automatically behind a simple RESTful API with SDKs in every modern language. Rather than have to build out all that infrastructure to begin with, developers can start with the Fediverse API, saving them a bunch of time and allowing them to focus on their unique idea.

It would start out with a free tier, allowing experimentation, and then scale up to affordable, use-based billing.

Add-on services could provide the aforementioned anti-spam, and there could be plugins from services like IFTAS in order to provide real human moderation for communities that need it.

Suddenly, developers can build a fully Fediverse-compatible app in an afternoon instead of in weeks or months, and know that they don’t need to be responsible for maintaining its underlying ActivityPub infrastructure.

A professional open social network (Fediverse VIP)

Status: idea only, but validated with domain experts.

A first-class social network with top-tier UX and UI design, particularly around onboarding and discovery, built explicitly to be part of the Fediverse. The aim is to be the destination for anyone who wants to join the Fediverse for professional purposes — or if they simply don’t know what other instance to join.

There is full active moderation and trust and safety for all users. Videos are supported out of the box. Images all receive automatic alt text generation by default (or you can specify your own). There is a first-class app across all mobile platforms, and live search for events, TV shows, sports, and so on. Posts can easily be embedded on third-party sites.

You can break out long-form posts from shorter posts, allowing you to read stories from Ghost and other platforms that publish long-form text to the Fediverse.

If publishers and brands join Fediverse VIP, profiles of their employees can be fully branded and be associated with their domains. A paid tier offers full analytics (in contrast in particular to Mastodon, which offers almost none) and scheduled posts, as well as advanced trust and safety features for journalists and other users from sensitive organizations. Publishers can opt to syndicate full-content feeds into the Fediverse. This becomes the best, safest, most feature-supported and brand-safe way for publishers to share with the hundreds of millions of Fediverse users.

Finally, an enterprise concierge tier allows Fediverse VIP to be deeply customized and integrated with any website or tool, for example to run Fediverse-aware experiments on their own sites, do data research (free for accredited academic institutions and non-profit newsrooms), build new tools that work with Fediverse VIP, or use live feeds of content on TV or at other events.

What do you think?

Those are some ideas I have. But I’m curious: what do you think would be most effective? Is this even an important goal?

I’d love to hear what you think.

Share this post

Share this post