This is my monthly roundup of the tech and media I consumed and found interesting. Here's my list for July.

A few people have asked about my process. I save my interesting links into Pocket, which is integrated into Firefox, my browser of choice. (I trust Mozilla to look after me more than any other browser manufacturer.) And then on the first day of the next month, I go back and re-examine everything I've saved.

If you're receiving this post via my email list, I use Mailchimp to gather the latest content from my blog's RSS feed and send an email at 10am. This morning I reset the timer to noon so that I could get the post out today. I'll return the setting to 10am once it's out.

By the way, I never use affiliate links. This post isn't trying to sell you anything - but let me know if it's useful, or if there are ways it could be more so.

Hardware

Apple Watch 5. I've been resisting quantifying myself, and my series 3 has been broken for a long time. But we're entering the fifth month of quarantine, and I wanted to make sure I was getting the exercise I needed. The series 5 is a nice improvement - it feels a great deal more responsive - and both the VO2 max and ECG functions are really good.

Withings Thermo. Because temperature is an indicator for covid-19, measuring it early and often, and seeing the trend (which is flat for me) is useful. I'm pretty bought into the Withings universe at this point, with the blood pressure monitor and the Body+ smart scale. They're well-built, the app that links them all is equally good, and I like that they're multi-user.

Apps

Libro.fm. I've never really been into audiobooks, but I recently changed over to listen to them when I drive and work out. Podcasts have been less enticing to me recently. Unlike Audible's parent company, Libro.fm doesn't sell technology to ICE to power deportations, and it gives a portion of sales to your local independent bookstore.

Nedl. I invested in Ayinde Alayoke and his team as part of Matter. The app they've created is really cool: a way to broadcast and search the content of live, real-time audio all over the world. He's raising a new round via Wefunder, and I was proud to join.

Books

The City in the Middle of the Night, by Charlie Jane Anders. Nominated for this year's Hugo awards, I was invigorated by this exploration of belonging, identity, and what it means to be human. Clearly informed by our present moment, it's an argument for something better than the divisiveness and greed we find ourselves subject to.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, by Ocean Vuong. Vuong's words seem to have a pulse of their own. Sad but occasionally hilarious, I recognized aspects of the immigrant struggle, and of being caught between two parallel universes (figuratively; unlike the previous book, this is not science fiction). Vuong is a poet, and that rhythm and sense of beauty shines here.

So You Want to Talk about Race, by Ijeoma Oluo. Ijeoma was the Editor at Large at The Establishment, a publication for writers marginalized by mainstream media that I was proud to support at Matter. It's taken me a long time to get to her book, which deserves its popularity. It weaves her own story with important anti-racist ideas, and I think it would make a great primer for people who are new to them, as well as an important reminder that we need to do the work for the rest of us.

Streaming

Palm Springs. Yeah, it's kind of dumb, but this 21st century Groundhog Day is also smarter than you think. I'm not sure I laughed out loud, but I had fun watching it. (Hulu.)

The Dog House: UK. All the niceness that made The Great British Bake-Off compelling viewing, directed into a show about adopting shelter dogs. It's the least demanding show you'll ever watch, and maybe also the cutest. I needed it this month. (HBO Max.)

The Act. Beautifully acted by an absolutely incredible cast (in particular, it makes Joey King seem woefully underused in everything else she's ever been in). A harrowing true story. (Hulu.)

Notable Articles

Black Lives Matter

What I Learned as a Young Black Political Speaker in Liberal White Austin. "What I fear that white Democrats do not understand is that Black Americans have no interest in playing team games if they do not see themselves alive on either team. Democrats offer minor reforms and change street names to Black Lives Matter Avenue. Many of them paternalistically say actions like defunding the police are unrealistic. But if I die in the best world that you can imagine, then there’s a problem with your imagination."

Wrongfully Accused by an Algorithm. "Mr. Williams knew that he had not committed the crime in question. What he could not have known, as he sat in the interrogation room, is that his case may be the first known account of an American being wrongfully arrested based on a flawed match from a facial recognition algorithm, according to experts on technology and the law."

What the police really believe. "Inside the distinctive, largely unknown ideology of American policing — and how it justifies racist violence."

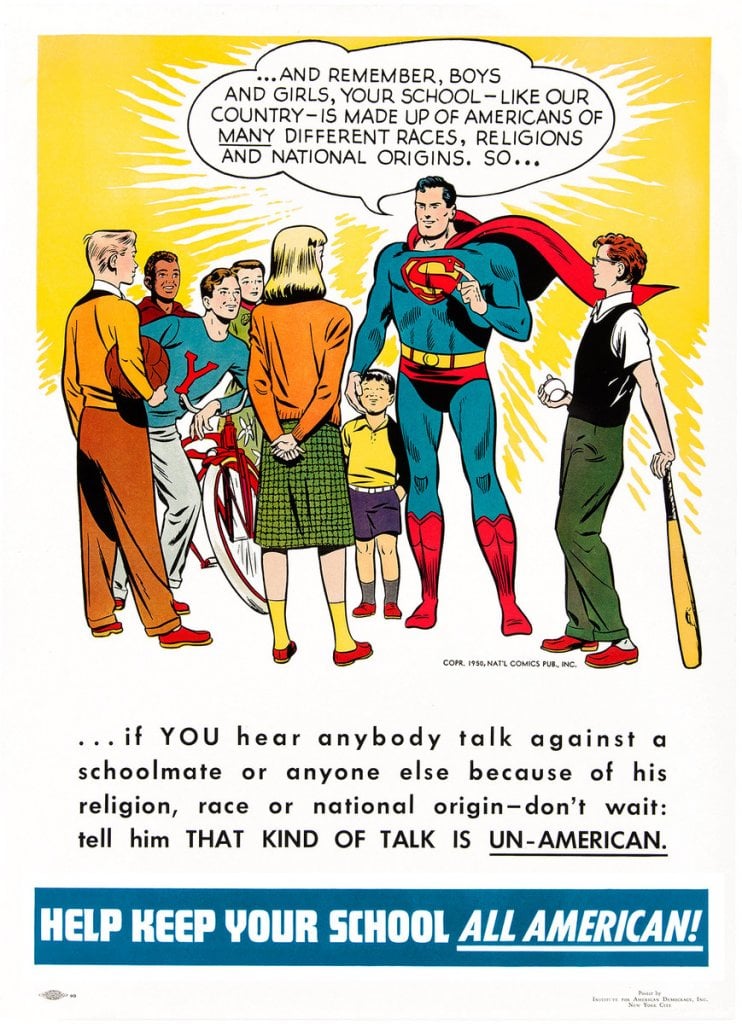

GOP senator introduces bill to stop federal funding for schools teaching ‘1619 Project’. "Republican Sen. Tom Cotton introduced a piece of legislation on Thursday that will prohibit the use of federal funds to teach the award-winning New York Times piece The 1619 Project in K-12 schools." Imagine being this racist, or being represented by someone this racist.

McClatchy journalists absolutely can show support for Black lives. I'm glad this was cleared up, but it seems a bit silly that it was ever a question. Support for human rights is not and should not be a political issue.

Breonna Taylor Is On The Cover Of O Magazine — The First One Ever Without Oprah. Arrest the cops who murdered her.

Trump's America

Lest We Forget the Horrors: A Catalog of Trump’s Worst Cruelties, Collusions, Corruptions, and Crimes. "This election year, amid a harrowing global health, civil rights, humanitarian, and economic crisis, we know it’s never been more critical to note these horrors, to remember them, and to do all in our power to reverse them. This list will be updated between now and the November 2020 Presidential election."

Minimum wage workers cannot afford rent in any U.S. state. "Full-time minimum wage workers cannot afford a two-bedroom rental anywhere in the U.S. and cannot afford a one-bedroom rental in 95% of U.S. counties, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s annual “Out of Reach” report." (Here's that report.)

Homeland Security fears widespread mask-wearing will break facial recognition software. Allow me to play my tiny violin.

Is this the beginning of Trump's Dirty War? "As if on cue, John Yoo, the legal architect of George W. Bush’s torture regime, has emerged as one of Trump’s newest advisors, helping craft legal-sounding justifications for Trump to expand his powers to dictatorial proportions." A genuinely terrifying comparison of Trump's recent actions to historical events in Argentina and elsewhere.

Anti-fascists linked to zero murders in the US in 25 years. Right-wing extremists, not so much. As many people have said, the difference is: right-wing activists want people to die, while left-wing activists want people to have healthcare.

“Defendant Shall Not Attend Protests”: In Portland, Getting Out of Jail Requires Relinquishing Constitutional Rights. "A dozen protesters facing federal charges are barred from going to “public gatherings” as a condition of release from jail — a tactic one expert described as “sort of hilariously unconstitutional.”" But not ha ha hilarious.

Esper requires training that refers to protesters, journalists as 'adversaries'. "A mandatory Pentagon training course newly sent to the entire force and aimed at preventing leaks refers to protesters and journalists as "adversaries" in a fictional scenario designed to teach Defense Department personnel how to better protect sensitive information."

Dismantle the Department of Homeland Security. By Richard Clarke! Let's not allow the people who were involved in George W Bush's administration absolve themselves of the war crimes they committed, but nonetheless, this is a remarkable editorial.

Culture and Society

Carl Reiner, Perfect. A completely lovely remembrance of Carl Reiner by Steve Martin.

It’s time for business journalism to break with its conservative past. Yes, please.

Magical Girls as Metaphor: Why coded queer narratives still have value. "From unhealthy power dynamics, such as student-teacher relationships; to biphobia, transphobia, body shaming and white beauty standards; to an over-saturation of tragic endings, “forbidden love” and coming-out narratives; I couldn’t really see myself in any of that. But as a young queer pre-teen, I did see myself and what I wanted to be in anime. Not often in yuri, surprisingly, but in magical girl anime and in idol anime."

Why Children of Men haunts the present moment. A beautifully bleak exploration of one of the best films ever made.

Q&A: The Fearless High School Newspaper Editor Covering Portland Protests. This is so incredibly cool and gives me hope for the future. "I found out that my dad has been tear gassed before, because when we were tear gassed he was like, “This is the worst tear gas I’ve ever felt.”"

When Did Recipe Writing Get So...Whitewashed? "Last year when my book was coming out, I had to take a stand against italicizing non-English words. It's a way that Western publications literally "other" non-white foods: they make them look different. But why can't dal and jollof rice and macaroni and cheese all exist in the same font style?"

Tech

Pivot to People: It’s Time to Build the New Economy. "Today’s calls for ethical, humane, responsible, regulated and beneficial technology, compounded with venture capital’s virtue signaling in solidarity with Black lives, brings us to a critical crossroads for corporate America." I really hope this is the future of the tech industry.

Spies, Lies, and Stonewalling: What It’s Like to Report on Facebook. "The company seems to be pretty comfortable with obfuscating the truth, and that’s why people don’t trust Facebook anymore."

Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. "We show, via a massive (N = 689,003) experiment on Facebook, that emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness. We provide experimental evidence that emotional contagion occurs without direct interaction between people (exposure to a friend expressing an emotion is sufficient), and in the complete absence of nonverbal cues."

The Adjacent User Theory. "Our success was anchored on what I now call The Adjacent User Theory. The Adjacent Users are aware of a product and possibly tried using the it, but are not able to successfully become an engaged user. This is typically because the current product positioning or experience has too many barriers to adoption for them."

“Hurting People At Scale”. "As it heads into a US presidential election where its every move will be dissected and analyzed, the social network is facing unprecedented internal dissent as employees worry that the company is wittingly or unwittingly exerting political influence on content decisions related to Trump, and fear that Facebook is undermining democracy."

Regulating technology. I strongly disagree with Benedict Evans on his conclusions - long-time readers will know I'm very pro anti-trust, and buy into Tim Wu's arguments completely - but his argument is worth a read.

Twitter says it's looking at subscription options as ad revenue drops sharply. Ads are dying; payments are likely to supplant them just about everywhere. Medium was far ahead of the curve, as was Julien Genestoux with Unlock.

New Survey Reveals Dramatic Shift in Consumer Attitudes Towards Advertisements In Quarantine. I mean, let's be clear: ads suck, and they always have. In the pandemic, our tolerance for bullshit has gone way down.

HOWTO: Create an Architecture of Participation for your Open Source project. I've created two major open source projects and helped to build a third. This is a really great guide which I'm happy to endorse.

Compassionate action over empathy. On building with compassion instead of empathy. This is an important distinction that I need to internalize more. "I worry that when we fixate on empathy, we stay focused and stuck on whiteness and the guilt that millions are feeling for the first time. It’s one reason I’ll no longer recommend White Fragility. The whole book stays on white feelings without switching to privileged action."

Image "Cloaking" for Personal Privacy. "The SAND Lab at University of Chicago has developed Fawkes, an algorithm and software tool (running locally on your computer) that gives individuals the ability to limit how their own images can be used to track them." Super-smart tech.

Mischief managed. "How MSCHF managed to dominate the internet — with fun!" As I mentioned last month, I'm a fan.

Microsoft Is in Talks to Buy TikTok in U.S. Simultaneously, the President is talking about banning it and not allowing Microsoft to buy it. Apropos of nothing, Facebook is about to come out with a competitor called Reels. I'm sure the ban is completely unrelated.

Share this post

Share this post

Sometimes it's important to step out of your life for a while.

Sometimes it's important to step out of your life for a while. There was one conversation I used to hate more than any other. I used to brace myself for it; grit my teeth in anticipation.

There was one conversation I used to hate more than any other. I used to brace myself for it; grit my teeth in anticipation. But I had also discovered the Internet, which felt like a magical, invisible layer on top of the world. Hidden in invisible corners there, where no-one else could find us, on newsgroups and IRC, not limited by geography, space or time, we reached out to each other. I believe we were the first generation of teenagers to make friends in this way. I think we were also probably the last to be allowed to travel and meet each other without supervision. We traveled across Britain to show up at "meets", where we acted like British teenagers do, loitering outside pubs, hanging out in parks, and cementing friendships that could not have been created any other way.

But I had also discovered the Internet, which felt like a magical, invisible layer on top of the world. Hidden in invisible corners there, where no-one else could find us, on newsgroups and IRC, not limited by geography, space or time, we reached out to each other. I believe we were the first generation of teenagers to make friends in this way. I think we were also probably the last to be allowed to travel and meet each other without supervision. We traveled across Britain to show up at "meets", where we acted like British teenagers do, loitering outside pubs, hanging out in parks, and cementing friendships that could not have been created any other way.